By: A.I. Root

Entertaining Angels Unaware

At one time in the spring of 1878, after paying all my debts I had about $3000 in the bank. The building I then occupied was soon after sold for $4500 so that I had, subject to my demand, about $7500. Nearly all my life I had been pretty badly in debt, for just about as soon as I saw any prospect ahead of taking things a little easier, I almost invariably got hold of some new speculation, and so it went. The sum mentioned was to build the factory and pay for the ground on which it should stand.

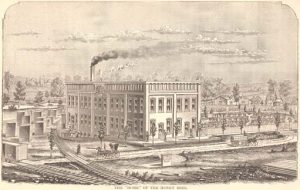

To save expense and to enable every one to have goods with the least possible delay, I wanted the factory as near the railroad as possible. After looking at all the available land in the vicinity, some one suggested that the county fairgrounds would answer nicely if they could be purchased. The grounds sloped gently to the south and east. There were pretty patches of woodland, a stream of water, and above all, one corner of the property came right close to the railroad station, nearer than any other piece of land that could be purchased.

I made a good cash offer for the grounds, but as they belonged to the people of the county, a day had to be fixed some time ahead for the consideration of the subject. As the time for the decision came nearer, there was much talk in regard to the matter and many were quite vehement in declaring that I should not have the fairgrounds. The day finally came and with it the decision that the sale would not be made. Another meeting was held, later, however, and it was decided that I could have the property at my first offer. If the prayer for this had no effect on the people it certainly had on myself, for I felt it to be so sacred a matter that I left it all in God’s hands and took no part in the talk myself, being perfectly willing to trust that what was right and best would finally result.

Raising Funds for the New Factory

The 17½ acres of land with its building cost me $3500, so I had $4000 left with which to build the factory. Trade was always dull in the Fall, and I knew from past experiences that I should run short, for with the new printing press, a new 50 H.P. engine and other expensive machinery, I feared I could not get through with less than $8000. Toward the first of September, before the roof was even on the factory, the money at the bank was all gone and what was still worse, although I had had thousands there a few months before without getting a cent of interest, I found I could get no further credit without paying 10 percent interest. Still further, I would have to have two good signers to back me, signers who were owners of real broad acres.

For years I had prided myself on the fact that I had never asked any one to sign with me, and therefore I excused myself for not signing with any one else, and I presume I had got to feeling a sort of pride in my name which was unencumbered with any responsibility for other people’s debts. I became a little important and declared I would not ask any one to sign with me, but Saturday night came and the men came for their pay as usual, never dreaming that the money would not be forthcoming as it always had been. A few looked disappointed and when I learned of one who went without the necessaries of life because I had not been as prompt as they had expected, my heart smote me. Perhaps this man had just such a soft blue-eyed baby at home as I had, and it might be I had been the means of depriving this little one of comfort because the father could not have his earnings on Saturday night.

As I went home in the darkness of the night, I bowed my head to the ground under the apple trees where I had gone many times before and of Him who never refuses to go our security when we are in the right, I asked to be shown wherein I had erred and what I should do. As a natural consequence of having been refused money at the bank, I imagined that the people there treated me with a sort of lofty indifference, and my first impulse was to declare that I would have nothing more to do with them, and that I would deposit my money elsewhere. After kneeling in the grass, however, I felt that I should root out all those feelings and instead of getting mad at the cashier, I should go and state plainly to him my exact circumstances and ask his advice. This put both him and myself in quite a different light, and I found he was the same good friend he always had been. The truth of it was he had never been the least unfriendly. Do you know what a hard thing it is for a banker to refuse to trust an intimate friend and acquaintance? But, if the cashier of a bank could not do this, he would be totally unfit for his position, and would most certainly lose it.

“If you object to asking any one to sign with you,” said he, “give your signers a mortgage and thus secure them from running any risk.”

What a sensible piece of advice, and yet it had not occurred to me before. Furthermore, he agreed to lay my case before the bank directors and see if an arrangement could not be made whereby I might have credit for all money taken in and be charged interest for only what I used and no more.

The arrangement was made and all that was necessary was to get two names of considerable land holders. A relative by marriage said his father would sign with me willingly, but that his mother must not be told of it. To my way of thinking, a man and wife are one and I made my request to both. The old gentleman seemed quite willing to accommodate me, but his wife whom I knew well, strongly objected. What a wicked thing it would have been to have secured her husband’s name to any paper without her knowledge and to have worried her in her old age, even if she had been extreme in her ideas. God forbid that I should ever get out of trouble in that way!

I stated the matter to a member of our church who owned considerable property and although he did not refuse I saw plainly that he preferred not to accommodate me. He very kindly told me that people were talking about the probability that I would get “swamped” in trying to do things on so large a scale, because my business was something that few could understand and one that even I myself could hardly name.

I told him that I could have built a wooden building and had it all paid for, or I could have built smaller at the risk of having to build again in a year or two, or I could have purchased a smaller engine and printing press, but all these apologies would have been short-sighted in the end. Or I said, I might stop work on the building and let it stand without a roof until I could earn some more money myself.

“No, no, you must not do that. I will get you the money to pay your men tonight and we will fix it before another week so you can get along.”

Do you know how much good such a friend does? My wife and I knelt together in our own room that night and asked God to tell us what to do to avoid trespassing on the good nature of any one, or making any one responsible for our own affairs. As it had been intimated that trouble might ensue if I should die suddenly, she suggested that I have my life insured for the benefit of my estate. This was done and a mortgage given, the signers being my father and a friend who had for many years been the superintendent of our Sunday school.

Paying for the Brick on the New Building

One Sunday late in 1878, the last hymn sung at church was “Jesus, I my cross have taken, All to leave and follow thee.” These lines kept ringing in my ears and the words followed me all through the week. My money matters were not all quite adjusted and one considerable bill had been presented that I was not able to meet. On Thursday the man who had furnished the brick for the new building said he had a balance due to him, and he must have it, and that was all there was to it. I asked the bookkeeper how much there was due him.

“Three hundred and twenty-three dollars and thirteen cents.”

“Mr. S., at just what day or hour must you have this?”

“I must have it on the 20th without fail.”

“All right, you shall have it.”

After he had gone the bookkeeper said:

“We will not pay the hands then today?”

“Yes pay them all.”

“But how will you meet all these demands if you do?”

Before I went to bed that night I told my wife all about it. I confess I began to suspect that some of my friends feared if they did not crowd me a little and get their money pretty soon, perhaps they might not get it at all. Suppose they should all hand in their bills as did the brick man and say they must have the money immediately? Said my wife:

“What would you do if they should?”

“Ask God to send the money or tell us how to get it as we have before.”

“But perhaps you are not doing right. I am not at all sure that God wished you to get in debt this way, and I can not think that it is right to keep so many at work when you can get along very well without them. As far as they are concerned, you are doing them little if any good, in spite of all your efforts at making them better.

“All to leave and follow me,” came into my mind, and I asked God to give me a plain evidence of his approval, by sending the money to pay those bills if it was his wish that I should go on as I had been doing.

This was on the 12th day of December. The next morning a visitor from quite a distance came in, and although I had been up and at work long before daylight, my work, writing especially was so much behind that I felt almost like refusing to stop. He was a very pleasant man, however, and I wanted to show him over the factory. Things were not going very well, and when we went into one room and found dirt and disorder, it tried me exceedingly.

As we walked along I tried to talk cheerfully, but it was only assumed. Finally, I said, “My friend, I am cross today. I was going to take considerable pride in showing you around, but I have been very much humbled.”

We started to go over to the apiary. Said my visitor, “Mr. Root, I wish to take a little liberty, and I may ask you some questions you may not care to answer.”

I told him I had no secrets in the world, and that he could ask me anything he liked.

“How much are you in debt?”

I told him as nearly as I could without going to the books.

“How much interest do you pay? Are there others connected with you in any way that would be involved if you had bad luck?”

“Only two people have undersigned me, and they are secured by mortgages as well as by an insurance on my life. I could get the money lower, but I should have to get signers and I do not wish to have my business in any such shape that a bad move on my part might involve others.”

He approved of this, and finally said, “Have you any bills coming due very soon that may trouble you to meet?”

I could not help looking at him in surprise at this, and he apologized, saying perhaps he was going too far. I assured him he was not and then continued.

“No,” said I, “I have some bills to meet that trouble me some, especially the balance I owe the man who made the brick for my building.”

“Well,” said he “I have a proposition to make you and I hope you will be frank to say if you do not wish to accept it.”

“There,” I thought, “I see through it all now. He wants to join in partnership with me.” You see I did not even then have faith enough to see the connection between this conversation and the prayer of the night before. His next words, however, opened my eyes and it all became plain.

“If it will be of service to you, I will send you $500 and you may keep it a year at 7 per cent. I will require no security, only your note of hand.”

“But why do you, an utter stranger trust me thus? How do you know I will not make a foolish use of the money and get us all into trouble?”

“Well, I think you are trying to do good and I want to help. I have been reading your ‘Home Papers’ for a few months and I got to thinking about it and wondering whether you might not be in need of a friend just about now. The more I thought about it, the more I thought I would like to come and see if a little money would not do you good rather than harm. I have seen you and am satisfied.”

I thought of the strange intertwining of events, of the lines of that hymn, of my frankness in telling him how annoyed I was about the disorder in the wax room. I thought, too, of what the Bible says of entertaining angels unaware, and how uncourteously I had treated visitors many times. I saw clearly that God was in it all, and I almost felt frightened as I realized how near He had been to me. Unless I lived a purer and better life, I felt almost afraid to take that money so manifestly from God’s own hand. I told my friend that God had sent him to me in answer to prayer. He did not dispute it, although he made no profession of religion.

I told of this circumstances at our prayer meeting and on several other occasions. A great many inquired if the money had come, and when I told them it had not, most of them replied that they would like to see it before they were convinced. Some thought it some new confidence game, and that I would be the loser in some way. Finally, I told some of them I would bring the check over and show it to them before the day I had agreed to pay the man for the brick. I stopped at my mother’s and told her. She, of course, had a faith like mine, but father said something would happen to prevent its reaching me in time. He thought the man might be taken sick, or the mails stopped by deep snows.

The cashier of the bank said it was a wonderfully strange thing, and asked if the man had not some selfish purpose in view. He asked if he did not carry away something, and said he had seen him with a package under his arm. I told him that the man had taken some goods, but had paid for them all.

By Thursday noon a letter came from a bank at least 1000 miles away containing a check for $500 in gold. In a letter received from my kind friend a day or two before, he said, “I hope you may meet your brick man with a smiling face next Thursday.”

The brick man came at the appointed time, and I judged from the expression on his face that he feared he would be disappointed. To be sure I could meet him with a smiling face and as we walked to the bank I told him of how God helped those who trusted him.