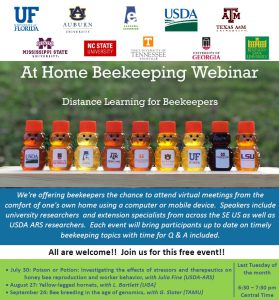

Previous studies have shown how neonicotinoids reduce the number bumblebees queens produced. Photograph: Richard Becker/Alamy Stock Photo

The world’s most widely used insecticide is an inadvertent contraceptive for bees, cutting live sperm in males by almost 40%, according to research. The study also showed the neonicotinoid pesticides cut the lifespan of the drones by a third.

The scientists say the discovery provides one possible explanation for the increasing deaths of honeybees in recent years, as well as for the general decline of wild insect pollinators throughout the northern hemisphere.

Bees and other insects are vital for pollinating three-quarters of the world’s food crops but have been in significant decline, due to the loss of flower-rich habitats, disease and pests and the use of pesticides.

Neonicotinoids were banned from use on flowering crops in the EU in 2013. The UK opposed the ban and allowed a limited “emergency” lifting of the ban in 2015, but has refused further suspensions this year. There is clear scientific evidence that neonicotinoids harm bees, but there is only a little research showing the pesticides harm the overall performance of colonies.

Previous work has shown that neonicotinoids reduce the number of bumblebee queens produced and severely cuts the survival and reproduction of honeybee queens. But the new research, led by Lars Straub at the University of Bern, Switzerland and published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, is the first to test how neonicotinoids affect male bee fertility.

They exposed drones to the levels of two neonicotinoids, thiamethoxam and clothianidin, seen in fields, and found that they had on average 39% less living sperm compared with unexposed bees. “Any influence on sperm quality may have profound consequences for the fitness of the queen, as well as the entire colony,” said the researchers.

Queen bees perform mating flights soon after emerging to collect and store sperm from multiple males, which is then used for reproduction over the queen’s lifetime. The drones reach sexual maturity at 14 days, but the researchers found 32% of the exposed drones were dead by then, and therefore unable to mate, compared to 17% of the unexposed controls.

“This could have severe consequences for colony fitness, as well as reduce overall genetic variation within honey bee populations,” the scientists said.

The researchers also found that exposed drones lived for 15 days compared to 22 days for the controls. They concluded: “For the first time, we have demonstrated that frequently employed neonicotinoid insecticides can elicit important lethal and sub-lethal effects on non-target, beneficial male insects; this may have broad population-level implications.”

Peter Campbell, from Syngenta, the company that makes thiamethoxam, said the new research was interesting. However, he noted that the sperm quality of all the drones in the study was reduced, compared to earlier work. “Given the multiple mating of honey bee queens it is unclear what the consequences of a reduction in sperm quality would actually have on queen fecundity,” he said.

Christopher Connolly, at the University of Dundee and not part of the research team, said: “This study is important, as failures in honey bee queen mating is reported to be a growing problem for beekeepers.”

He added: “Although the insecticide levels used in this study are realistic, it is unclear whether both neonicotinoids are commonly consumed together at these levels.

“Therefore, it will be important to investigate the impact of the neonicotinoids separately. Importantly, this study demonstrates the complexity of the possible consequences from chronic exposure to pesticides and these are not assessed during safety testing. Therefore, this study further supports the need to adopt the precautionary principle on neonicotinoids.”