By: Tom Rearick

Bee kills from pesticide treatments are not new.

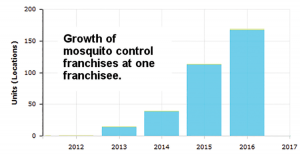

What is new is a rational fear of the Zika virus and the rapid growth in commercial mosquito abatement franchises that feed on that fear. Many of these companies spray and fog at all hours of the day, in all wind conditions, and use pesticides that are highly toxic to honey bees and other beneficial insects and aquatic life.

What is new is a rational fear of the Zika virus and the rapid growth in commercial mosquito abatement franchises that feed on that fear. Many of these companies spray and fog at all hours of the day, in all wind conditions, and use pesticides that are highly toxic to honey bees and other beneficial insects and aquatic life.

To reverse this trend, beekeepers need to communicate to neighbors and elected representatives that there are better ways to fight Zika than the scorched earth policy of indiscriminate fogging and aerial sprays. Zika is a scary virus that causes birth defects. Any attempt to minimize that threat may end any productive dialog with a neighbor. Instead, beekeepers need to become better communicators, better entomologists, and more expert pesticide applicators than the guy that drives a mosquito control panel truck.

Failing to take an active role in mosquito control education means abdicating that role to mosquito control companies that are disinclined to protect honey bees, beneficial insects, and aquatic life. Lacking better information, more households will sign abatement contracts with pest and mosquito control companies. There will be more drift of deadly pyrethrin clouds and more heartrending bee kills.

Failing to take an active role in mosquito control education means abdicating that role to mosquito control companies that are disinclined to protect honey bees, beneficial insects, and aquatic life. Lacking better information, more households will sign abatement contracts with pest and mosquito control companies. There will be more drift of deadly pyrethrin clouds and more heartrending bee kills.

Knowledge is our weapon. Share it with your neighbors. It wouldn’t hurt to also share a bottle of local, pesticide-free honey as well.

What is the Zika Virus?

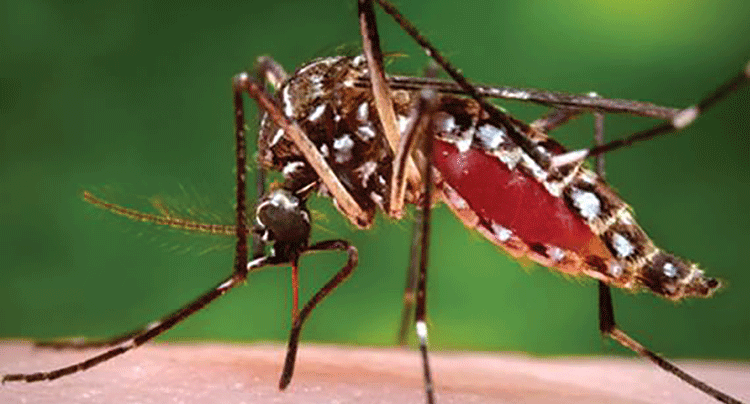

Zika virus is a flavivirus, related to yellow fever, West Nile, and dengue. There are no vaccines to prevent Zika or medicine to treat the infection. Zika is transmitted primarily by Aedes species mosquitoes that bite during the day and night. Infection during pregnancy can cause congenital brain abnormalities, including microcephaly to the unborn child.

Is Zika in the United States?

Yes. As of March 29, 2017, there have been 5182 cases of Zika virus reported in the United States. 4886 of those cases were from travelers returning from affected areas. 222 cases were acquired through local transmission in South Florida (216) and Brownsville, Texas (6). Local transmission means that local mosquitoes have been infected with the virus and are spreading it to people in the area. 74 cases were acquired through sexual transmission (45), transmission from a mother to an unborn fetus (27), and other means (2).

How is Zika spread?

Zika is transmitted mostly by the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito (Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus). The Asian Tiger mosquito (Ae. Albopictus) is found throughout most of the eastern and southwestern states and bites during the day. Zika is also potentially spread by humans through sexual activity, blood transfusion, and from a mother to her unborn fetus.

How can Zika be avoided?

Since there are currently no cures or vaccines for Zika, it is important to avoid the Zika virus:

- Reduce the likelihood of mosquito bites (see below)

- Reduce the mosquito population (see below)

- Avoid traveling to areas with Zika outbreaks. This includes most equatorial countries, south Florida, and Brownsville, Texas.

- Avoid sexual intercourse with individuals from Zika outbreak areas

What can be done to avoid mosquito bites?

- Add a fan to the porch. Mosquitoes are weak fliers and cannot navigate in a fan-induced wind. If you eat outdoors, a fan above and a small alternating fan on the floor will protect you above and below the tabletop.

- Repair small holes in door and window screens.

- Use a mosquito repellent such as DEET or Picaridin. Alternatively, Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus and IR3535 are biopesticide repellents made from natural materials.

- Pregnant women should wear lightweight long sleeves, pants, and socks when outdoors.

- Reduce mosquito populations – see next section.

What can be done to reduce mosquito populations?

- Avoid puddles and standing water no matter how small.

- Pick up toys, cups, bottles, or other yard clutter that might retain water.

- If you have a bird bath, wading pool, or small water feature, try adding a mosquito dunk. Each dunk contains a bacteria, Bti, that is harmless to humans and bees but deadly to mosquito larvae. Alternatively, change the water once a week or add a fountain to keep the water moving.

- Clean out rain gutters so that rotting leaves do not dam up water.

- Stock permanent water pools, such as ornamental ponds, with mosquito larvae eating fish such as Gambusia

- Drill drain holes in old tires. Add drainage ditches to prevent standing water after rainstorms.

- Put up bat boxes. A little brown bat – a common bat in the US – can consume about 600 to 1,000 mosquitoes in an hour. A nursing little brown bat mother may consume as many as 4,500 mosquitoes in a single evening – more than her body weight in insects. Unlike pesticide applications, bats are free and they work to reduce the mosquito population every night.

- Mosquitoes hang out in tall grass during the day so keep weeds trimmed and cut grass often.

If a homeowner must spray, what is the correct way to do it?

If a homeowner must spray, what is the correct way to do it?

Some homeowners (and mosquito control companies) are going to spray. Period. We are all better off if applicators are knowledgeable in the correct way to select and apply insecticide.

- Avoid spraying flowers in full bloom.

- Apply pesticides after sunset or before sunrise. Bees do not fly in the dark.

- Avoid aerial spraying or fogging. But if you must, do not spray or fog during windy conditions. Optimally, apply the pesticide directly to the ground using a low pressure, large droplet sprayer. This greatly reduces the drift of pesticide off of your property.

- Know that some pesticides are less harmful to honey bees and beneficial insects. The bulletin How to Protect Honeybees from Pesticides (https://www.clemson.edu/public/regulatory/pesticide_regulation/bulletins/bulletin_5_protecting_honeybees.pdf) provides useful information on the selection of pesticides.

- Avoid pesticide formulations of dust or wettable powders which are similar in size to pollen grains. Instead, use granulars, solutions, or soluble powders.

- Spray lower limbs of shade trees, shrubs and other non-flowering plants to reduce adult mosquito population. Bees do not frequent those locations but mosquitoes do.

- Understand that in addition to gathering nectar and pollen from flowers, bees also gather water in the Summer as a means of reducing temperature inside the hive. If a bee-deadly pesticide gets into water, it is likely to be collected by a honey bee.

- Pesticide applicators should notify local beekeepers before a pesticide is to be applied. Beekeepers can cover their hives with drop cloths. That will help protect the colonies from drifting pesticide but know that pesticide applied to flowers in full bloom is likely to end up in bees and spread to other bees in the hive. Beekeepers should also change the water source that they provide for bees.

- Please use pesticides that have the shortest persistence in the environment. Pesticides that persist are more likely to be washed into streams where they can kill aquatic life.

- Know that mosquito treatment companies typically use pesticides from a group of chemicals called pyrethroids that are promoted as being safe and natural. They are – to humans – but these pesticides are highly toxic to pollinators and other beneficial bugs, fish, and small aquatic organisms.

- Understand that the benefits and dangers of pesticides, as represented by commercial mosquito treatment companies is often at odds with information published by evidence-based government and university research centers.

- If you must spray, spray only as needed. Contract spraying on a predetermined schedule wastes pesticide and money and may contribute to pesticide-resistant mosquitoes.

How does Zika impact beekeepers?

Every time a news story covers the Zika, West Nile or some other mosquito-borne virus in the U.S., phones start ringing at pest and mosquito control companies. In the mind of most homeowners, calling a mosquito control company is the most rational response. A panel truck shows up – at any hour of the 9-5 work day – and workers start fogging the yard with pyrethrins. If the company is lucky, they will sign a recurring contract that guarantees multiple visits.

Pyrethrins are relatively safe to vertebrates but deadly to invertebrates such as honey bees, native pollinators, and dragonflies (that eat both mosquito larvae and mosquitoes). A cloud of pyrethrin can drift into an apiary or – if sprayed on flowers – toxic nectar and pollen can be carried back to the hive.

How can beekeepers prevent bee kills?

There are two approaches to preventing bee kills. Success in the first approach makes the second approach unnecessary.

Cultural Approaches

Bee kills are difficult to prevent unless you have neighbors that are educated in alternatives to fogging and are willing to work with you and inform you ahead of time of sprayings.

Tactical Approaches

If you know that a spraying is going to occur, you must protect your bees from drift and from flowers and water that were sprayed.

- Minimize effects of pesticide drift. These techniques will only work if you are warned ahead of time.

- Determine if your hives are downwind from the spraying

- Move the hives to a safe location if practical

- Cover the hives with a breathable ground cloth and wet it down to cool the colony.

- Change water sources that were exposed to drifting pesticides

- Minimize effects of toxic forage and poisoned water.

- Run sprinklers or misters to keep foragers in their hives. They will forage less if they think it is raining.

- Change the water that you provide to bees.

Help a colony survive a pesticide exposure

If a colony has lost most of its foragers but is stable after a day and still has plenty of honey and pollen, it has a good chance of surviving on its own. Move the surviving hive to a less toxic location with clean forage if possible. If you cannot move the hive or if there is insufficient forage, provide honey or sugar syrup. Provide clean water. The queen may stop laying for awhile but should resume. If she does not resume laying in a week or so, replace her.

However, if bees continue to die, there is most likely toxic pollen and nectar in the hive. The bees will continue to die until they are separated from the now toxic pollen and nectar. Shaking bees into a clean hive followed by a feeding may save them. Wax foundation that has absorbed pesticide cannot be rinsed out – it should be destroyed.

Help! My bees are dead. What should I do?

The experience of finding your bees dead in piles is devastating. One tempting response is to withdraw from a hobby that causes such a painful experience. Another response is to recognize that – as stewards of our environment – much work remains to be done and that courageous individuals can make a difference.

Before there can be any legislation to protect honey bees, there must be evidence that bee kills occur with enough regularity to enact legislation in the first place. That is why beekeepers should report all bee kills at state and federal levels.

The email address for the Environmental Protection Agency is beekill@epa.gov. The Honey Bee Health Coalition Quick Guide to Reporting a Bee Kill Incident (http://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Quick-Guide-to-Reporting-a-Bee-Kill-Incident-Final-122316.pdf) is available to help beekeepers report an incident to the State, the EPA, and pesticide manufacturers as well as how to obtain non-governmental help.

Additional Resources

American Mosquito Control Association (http://www.mosquito.org/)

EPA: Protecting Bees and Other Pollinators from Pesticides (https://www.epa.gov/pollinator-protection)

EPA: Tips for Reducing Pesticide Impacts on Wildlife (https://www.epa.gov/safepestcontrol/tips-reducing-pesticide-impacts-wildlife)

UGA: Pollination: Protecting Pollinators from Pesticides (http://caes2.caes.uga.edu/bees/pollination/protecting-pollinators-pesticides.html)

Template of a letter to send your neighbors can be downloaded at http://metroatlantabeekeepers.org/zika_letter.doc

In the Summer of 2016, I lost three colonies to single pesticide event. In the Spring of 2017, I assembled the following into a gift bag and gave it to each of my five nearest neighbors.

A letter from my wife and myself (you can download a Word template at http://www.metroatlantabeekeepers.org/zika.php)

- A brochure from the University of Georgia School of Entomology: Not Every Bug Is A Bad Bug

- A printed document from Clemson University titled How to Protect Honeybees from Pesticides

- A small recipe brochure from the National Honey Board

- A bottle of my own honey

- The response from my neighbors has been very positive. They are now armed with knowledge and have a vested interest in protecting beneficial insects.

Tom Rearick

If I knew that flowers in full bloom were being sprayed and my hives were not downwind, I would immediately dump honey into a pan and set it out in the apiary. The bees would find it and prefer it to other potentially toxic nectar sources. Open feeding is usually a bad idea because of the possible transfer of disease but that risk is much smaller than a known pesticide spray. This approach might work for a day in a small apiary but that may be all you need because many pesticides break down in sun and humidity. At any rate, the pesticide is less potent after 24 hours. Diluting the honey with water might make it last a little longer. If you lack the honey, you could make a cane sugar syrup.

Tom Rearick

Tom Rearick is a UGA Master beekeeper, webmaster of the Metro Atlanta Beekeepers Association, and publisher of the BeeHacker blog (beehacker.com). This article is modified from one Tom wrote for the Metro Atlanta Beekeepers Association: http://www.metroatlantabeekeepers.org/zika.php and is used here with their permission.