The Representation and Symbolic Meaning of the Honey Bee through Time.

By Isabelle Hopkinson

From the Greeks to the Egyptians, from Napoleon to the Mormons and Karl Marx to the City of Manchester, the bee and more specifically the honey bee, has been a persistent recurring image throughout human history. Following the Manchester bombing attacks in 2017, the image of the bee became a defining symbol to reflect a collective show of solidarity to the tragedy. In fact, the bee had long been an emblem for Manchester, symbolizing the city’s industrial past when workers were dubbed “busy bees”. The crest on the City’s arms include Seven bees.

Prior to going to University to study anthropology I became interested in the way in which the bee has been used and represented in different cultures and societies through time, the reasons why and the meaning given to it, which hope to reveal in this short article.

The Bee in Ancient Greek society (2000-300 BC)

Bees and honey were a major and persistent symbol in Greek culture and were often linked with knowledge, health, and power. Bees were considered servants of the gods and honey was worshipped due to its healing attributes and power. They are represented in in jewelry, money, and statues of goddesses.

One of the most famous legends of the gods in Greek history is of ‘Melissa’, the goddess of the bees. In the human world, priestesses were referred to as ‘Melissae’ in the temples of the goddesses. In Greek mythology, Melissa was a nymph who was shown the use of honey by the bees. She was one of the nymph nurses to Zeus when he was born to Rea in a cave that was sacred to bees. There have been two versions though of the myth. One states that the bees nurtured Zeus, whose son was then nurture by the ‘Melissae.’ The other states that it was Zeus who was fed with the milk of goats and with honey by the ‘Melissae.’

Melissa, the Bee goddess of Mount Eryx. (British Museum, Wikipedia)

Honey is often referred to as a gift, the ‘nectar of the gods.’ Greek gods were often described or depicted drinking ambrosia. Historians have suggested that ambrosia was a representation of honey due to its colour and taste. Ambrosia was believed to quench any thirst or hunger for the immortal being of Mt. Olympus. It did, however, have other purposes such as being used as a balm for gods to transfer immortality. For example in the myth achilles was bathed in honey and passed through the fire so that all his mortal parts would die. However, because he was held by his ankle, this was the only vulnerable part of him. The mystique of ambrosia was reinforced in the myth of Tantalus who is punished for stealing the ambrosia and giving it to humans. Those who drank it would no longer have blood running through their veins bu Ichor (the mythical fluid in the veins and arteries of the gods).

In other legends such as those surrounding Zeus, bees were represented as messengers between gods and men and carriers of wisdom and knowledge. In the story of Apollo and Delphi, the Boeotian (a man from central Greece) who had come to consult Delphi referred to another oracle but on their journey he and his companions became lost. They followed a swarm of bees that lead them to Trophonios. Here the bees are represented as guides with close links to the Oracle, leading them to find another one. Through this myth bees are associated with prophecy, knowledge and foresight.. a representation that continues to the present day.

Images of Melissa. (Ransome)

The Ephesus Statue

Honey also played a very practical role in Greek society and in everyday life. It was a source of food and associated with celebration and good times.

Honey was also widely used for healing wounds and preservation, essential requirements for health and prosperity. It is therefore not surprising that the bee and honey featured prominently on key material artefacts including jewelry, statues, pots and coins. Moreover, as Greek civilization spread this meant that the bee began to appear in other cultures such as that of Ephesos (Ephesus, Turkey) on items such as coins which are themselves both a physical and symbolic representation of wealth.

The Bee in Ancient Egyptian History (3000-30 BC)

Ancient Egyptian society is regarded as the first great civilization period, lasting nearly 3000 years. As in ancient Greece, bees and honey feature in myths and legends where formed an important part of everyday life – including honey being used to pay tax.

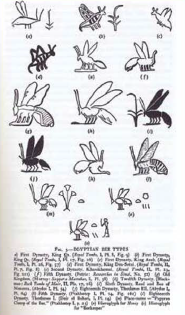

The bee appeared in writing, sometimes to refer to the bee or bee keeper but also in terms of Royalty. The ‘bee’ was the name given to the lower half of Egypt as it was full of flowers which the bees would pollinate. The Pharaoh was know as ‘he of the sedge and bee’ which translates as the King of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Representation of the bee throughout Ancient Egyptian times. (Ransome)

The sun god Ra plays a central role in Ancient Egyptian culture. Ra was described as the father of the gods and the creator of the pantheon. All gods should represent an aspect of Ra whilst Ra represents all gods. Ra was considered to be the creator of the seasons, animals and mankind. The legend is that bees were created from his tears that fell to earth passing on a secret message. The right eye was said to have healing and protective power. Bees were regarded as servants of the gods, delivering messages and healing powers from them to mankind. The role of bees as messengers of the gods is also central to the myth of the lost god Hittite Telepinu. Telepinu was the god of farming who one day due to frustration stormed off into a meadow and fell asleep. His anger upset the world of nature and nothing grew in the fields. Due to the destruction the gods tried to search for him but to no avail. Eventually the bee was asked to find him and did so, stinging him to wake him up which only increased his anger. However, the gods were able to calm him and he returned to tend his fields and bless his rivers.

The Sun god Ra. (Cover of Professor Kritsky’s remarkable book on the bee in Egyptian times)

Unlike in the myths of Ancient Greece, the bee also features as a symbol associated with death and resurrection of the soul and Egyptian culture showed a belief in the afterlife. Pyramids were constructed to provide the Pharaohs with all the things they would need in the afterlife. The mummification process was to preserve all the vital organs so that they body could be resurrected and images, artefacts and symbols of bees are commonly found in tombs and burial chambers.

Bees in the time of Medicis. The plinth of the Ferdinando I de’ Medici (r. 1587-1609), in Florence is decorated with bees surrounding the queen.

The bee and honey are manifested in the material artefacts, myths, beliefs and practical everyday lives of both both ancient Greek and Egyptian society. As we turn the clock forward, we see that the bee and honey continue to appear with remarkable regularity in different cultural settings. As we shall see, however, their appropriation, symbolism and meaning shifts in line with cultural value and wider historical, social and economic context.

Fortana delle Api in Rome, completed in April 1644, to relinquish the thirst of both both people and horses, the father spouting form the mouths of honeybees.

Napoleon

The positive qualities associated with the bee and honey continued well beyond ancient society. As an example, the bee became a significant symbol in the Napoleonic period. Following the French Revolution (1789-1799), Napoleon became Emperor of France (1804) replacing the monarch dynasty that had ruled for several hundred years. Royalist assassination attempts threatened Napoleon. He asserted his power and authority by adopting a number of features of the Ancien Regime, including moving into the palace of Versailles. He created a council commission it sole purpose being to ‘plan everything to do with the coronation of the Emperor and Empress.’ They decided to adopt the bee as his symbol as it represented immortality and resurrection.

The symbol of the bee flooded the courts of Napoleon and became associated with many different qualities including hard work, industriousness, vigilance and, due to its production of honey, sweetness and benevolence.

The Napoleon bees used as part of the cover design of a beautifully leather bound book. (Geoff Hopkinson)

The bee also had historical links with ‘Childeric I, founder in 457 of the Merovingian dynasty,’ who ruled Northern Gaul (modern day France) from 437-481 AD. The tomb of Childeric was discovered in 1653 and found to contain many precious artefacts including 300 winged bees.

The Childeric Bees. (Wikipedia)

Bees and Freemasons

It was not just the Freemasons who adopted the hive as a symbol to represent ideals and virtues. Nineteenth-century leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day saints (more often referred to as Mormonism) consciously created symbols to promote their democratic ideals. They symbols of the bee encompassed all aspects of Mormon life as shown by their use in modern temples, caskets and tombstones. The origins of the bee and beehive are reputedly drawn from the ‘Book of Mormon’ published in 1830 by founder, Joseph Smith. It is also said that in the journey to what is now Salt Lake City, they ‘did also carry with them deseret which, by interpretation, is the honey bee.’

Masonic Firing Glass

Bees and political economy

Bees and political economy

The advent of mass industrialization from the 1830’s onward saw the bee and the hive being appropriated as symbols of industry and the virtue of hard and selfless working for the greater good. The bee was adopted by the Manchester Council as long ago as as 1842, and workers in the city were often referred to as being ‘as busy as bees.’ The beehive has often featured in the political imagination as an allegory for the working class, drawing from parallels with a proletariat ‘which lives from the sale of its labour and does not draw profit from any kind of capital.’

Others viewed the hive less favourably, highlighting how the ‘hive’ symbol removes individuality and showed a work force no longer being celebrated for their unique individual talents. During the cold war, rather than the virtuous association of collectivism, bees began to be used to represent the Russians as evil collectives and symbols of anxiety.

The Coat of arms of Manchester. The seven bees above the helmet are a tribute to Manchester’s long association with industry. (Wikicommons)

Conclusion

In conclusion, symbols of the bee, hive and honey appear in many different cultures and societies through human history. This short article has covered a small number of examples to show the wide range of symbols, representations and meanings. Whilst the majority reflect positive or virtuous characteristics of bees they can also be interpreted as displays of wealth, power and control. This begs the questions not only of what the bee represents but who creates, controls, and reproduces they symbols and material artefacts what purpose.

Isabelle Hopkinson

Based on a level Project Qualification submission by Isabelle Hopkinson supplemented by additional work as a 1st year student reading Anthropology at Exeter University