By: Shawn Christensen, UC Davis

Certain species of floral bacteria can enhance pollen germination, according to a study published from the University of California, Davis in the journal Current Biology. “This is the first paper documenting stimulation of pollen germination by non-plants,” said first author Shawn Christensen, a doctoral candidate in associate professor Rachel Vannette’s laboratory in the Department of Entomology and Nematology. “Nectar-dwelling Acinetobacter bacteria stimulate protein release by inducing pollen to germinate and burst, benefitting Acinetobacter.”

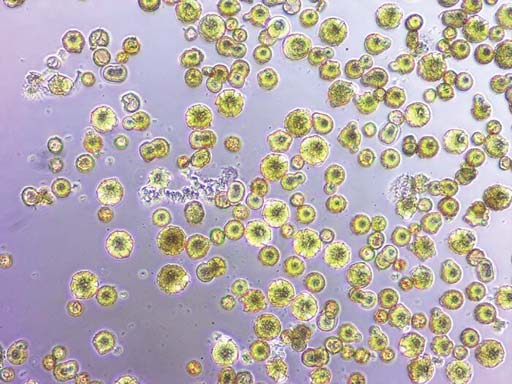

Acinetobacter is a genus of bacteria very common in flowers. They are usually among the most abundant bacteria in nectar and are often found on other floral tissues, including pollen and stigmas.

The authors collected California poppie from the UC Davis Arboretum and Public Garden, and Acinetobacter primarily from nearby Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve, which is part of the UC Natural Reserve System.

“Despite the essential nutritional role of pollen for bees and other pollinators, we still know very little about how pollen is digested by anything,” Christensen said. “We found out that certain bacteria in flowers, Acinetobacter, can send a chemical signal to pollen that hijacks its systems and tells it to open the door from the inside – releasing protein and nutrients for the bacteria.”

Christensen said the bacteria can double the amount of protein released from pollen. That makes it important for bacterial growth, but it could also be exploited by bees or other pollen consumers to get more nutrition from their food.

The question of how organisms actually eat pollen has been a long-standing one. Pollen is well-protected by layers of resistant biopolymers, and it’s unclear how pollen-eaters get through those protective layers.

“The bacteria have found what looks like a fairly unique and very effective way to get nutrients, which are otherwise scarce in a flower environment,” said Vannette, a UC Davis Hellman Fellow. “It is a very neat biological trick. This finding opens the door for a lot of exciting new research: How do the bacteria do it? Given that Acinetobacter is often found on pollinators, do pollinators benefit from this? Could bacterial action on pollen make it more or less beneficial to pollen-eaters? And what about plants? Could the bacteria be reducing pollination by causing pollen to germinate before fertilization? We aim to investigate many of these possibilities in future work