By: Don Coats

Watch for this killer. It’s not passed by Varroa.

Introduction: This article reports on a honey bee colony struggling for survival against an infection of CBPV. It describes history-predisposing factors and the sickness scene, and reviews the diagnostic report. A video link provides an opportunity to witness behavior of the sick bees on grass in the perimeter of the hive.

Background: Colony deaths, “Winter dead-outs” are often blamed on virus infections, especially if the colony had a history of high mite infestation. Varroa mites weaken bees by leaching their fat bodies and leaves them vulnerable to virus infections. However, recognized signs of these virus infections are rarely observed in action since beekeepers north of the Carolinas wait until spring to inspect their hives. This case occurred in southern Chester County, Pennsylvania, among a community of five different beeyards within a two mile radius, none, except for this hive reported similar signs.

Sick bees from the grass and some from the inner covers were collected and mailed live to Bee Informed Partnership (BIP) for virus testing.

Patient History: Knowing the history of a mammalian patient helps a clinician diagnose and characterize human or pet diseases. It was analogous here in knowing that the colony was a captured swarm 10 months prior to disease onset. It had very high mite loads in the previous Fall, 12%, much higher than six other colonies in the same yard, despite standard treatments of Amitraz strips in mid-summer and OAV in the fall. Signs of disease became very evident in late February, when hundreds of addled and dying bees were altruistically scattered around the hive during warmer days.

Below is a link to a video of the dying bees. The pattern exhibited for several weeks but the colony survived. Signs shown by these bees did not totally fit the descriptions of bees suffering from CBPV, such as trembling, bloated abdomen and “hairless black syndrome.” They did seem to show partial paralysis and present thousands of crawling bees around the hive.

https://www.dropbox.com/s/qzl6hxl6tatjwz5/MVI_6392.MOV?dl=0

As a probable credit to a strong queen, this colony, having dwindled to a population of three frames of bees in early March, seemed to recover by mid-April. The virus appeared to not affect the queen and the workers didn’t succumb until late maturity. In mid-April, foragers showed good entrance activity and regular amounts of pollen were entering.

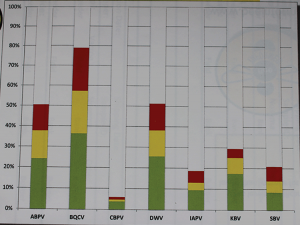

Virus assessment charts can be challenging to interpret, and it is good that laboratory staff usually provide commentary to do that for the beekeeper. It is particularly interesting that most reports find several different viruses at different intensities in the same sample but this one revealed only one of the 7 possibilities and at high “concentration”.

Red color code indicates that portion of positives which most likely effect hive health.

BIP tests for seven viruses significant to colony health. The National Agriculture Genotyping Center, (NAGC) tests for a similar array plus a “satellite” virus.

Clinical signs of these different viruses are described in various text sources. The following is a summary of the description of signs associated with CBPV as found in Honey Bee Diseases & Pests, by the Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists.

“CBPV causes abnormal trembling in adult bees, partial paralysis resulting in crawling and limited flight ability and bloated abdomens. In serious cases, thousands of bees can be seen crawling on the ground at the hive entrance. In addition, infected honey bees sometimes have reduced amounts of body hair and will appear darker and shiny. Hence CBPV is often referred to as hairless black syndrome.”