By Jeff Wells

Don’t let all the wooden crates, hay bales and “meet the farmer” signs fool you: Locally sourced products have become a big business for supermarkets.

What began as a limited marketing effort to capitalize on the surging interest in farm stands and community supported agriculture has evolved into a major growth opportunity as consumer desire for fresh foods, emerging brands, unique flavors, and transparency has expanded. That has piqued the interest of everyone from small cooperative grocers to giant Wal-Mart who are eagerly investing in products that are grown, baked, butchered and manufactured in the same communities where their stores operate.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture predicts sales of locally produced foods, which hit $12 billion in 2014, will surge to $20 billion by 2019. Management consulting firm AT Kearney found 78% of consumers said they will pay more for local products throughout the store.

“With an overwhelming percentage of customers still saying fresh is the most important factor in their purchasing decisions across categories, a strong stand in local food can bring increased sales,” AT Kearney found in a 2015 report.

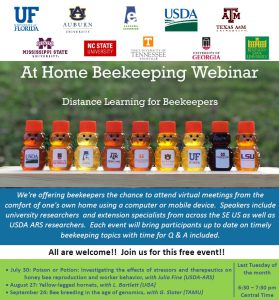

While the desire for more locally raised products has grown, the processes that move these items from the fields, beeyards, bakeries, and small factories to the shelves have struggled to keep pace. As demand increases, everyone from suppliers to distributors and retailers are laboring to innovate a process that, at its core, relies on sourcing a small amount of product from many producers. They’re aggregating, streamlining, investing, educating, re-branding and applying technology in ways that belie local’s quaint, down-home image.

Investing in local

Retail distribution systems are designed to deliver as much uniform-quality product as possible in as few trips as possible — something that local producers, which are vulnerable to supply shortages, weather and other issues, often struggle with.

Breaking their distribution systems down or offering shortcuts has proven difficult for grocers. Adding extra delivery routes can be costly. Even if a local supplier can handle its own deliveries, retailers already receive a high volume of store shipments, and often operate limited delivery windows. Suppliers also must pass food safety checks and quality inspections that can be time and cost intensive for both parties.

North Carolina offers an interesting case study. The state has a rich agricultural history, and is home to a strong and growing network of small farmers. It’s also the center of significant retail growth, with companies like Wegman’s, Publix and Lidl set to move in alongside established players like Ingles and Food Lion.

But farmers and grocers are struggling to work together, according to Fred Broadwell, former education director with the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association and current head of Local Organic Y’All, an organization that advocates for local and sustainable agriculture. Small farms in the state have scaled up to meet demand from farmers markets and CSAs, but they need further investment to meet demand from nearby supermarkets, he said.

“We’re at a serious plateau, and we’re not moving up to that next step of much broader access,” Broadwell told Food Dive.

Last year, Local Organic Y’All assessed 16 North Carolina supermarkets on their local offerings, scoring them on criteria that included product variety, investment in local food systems, and plans for the future. With the exception of Whole Foods and Lowe’s Foods, all retailers scored below 50 points out of a possible 100.

Part of the problem, Broadwell and other sources noted, is that “local” is not a legally defined term. For some retailers like Wegmans it means within 100 miles of a store, while others define it as within the same state or within a generally defined region. As local agricultural advocates point out, loosely defined sourcing standards tend to prize large operations that are at odds with consumers’ definitions of local. According to a recent poll by AT Kearney, 96% of consumers define “local” as anything sourced within 100 miles of a store.

Broadwell said local farmers are eager to work with supermarkets, but they also need retailers to work with them. Getting their supply and operations up to speed requires time and investment, while standards in food safety and other areas are often burdensome. Most local producers interested in sourcing to retail markets will get certified through the USDA’s Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) program, but some retailers require more expensive international certifications instead.

“There’s a concern that this could continue making it impossible for some of the small to medium sized companies to get into the system,” Broadwell told Food Dive.

Big companies go local

Many large retailers whose size might seem at odds with local sourcing values are increasing their supply of these items. Southeastern Grocers, which estimates 30% of its in-season produce comes from local sources, recently announced a new policy that prioritizes fruits and vegetables grown in the southeastern U.S. above other options. Meijer, whose stores average around 200,000 square feet, spends more than $100 million each year on local produce grown within the six states, where it operates.

In 2010, Wal-Mart, the nation’s largest grocer, pledged to double its sales of locally grown produce. By 2015, the company had exceeded that goal, with $825 million in revenue — more than 10% of its total produce sales. The company wants to double sales again to $1.65 billion by 2025.

The reactions to this growth has been mixed. While some have noted the initiative brings attention to the “grow local” movement, others note Wal-Mart’s push for low prices and year-round supply have been more of a burden than a benefit for farmers.

Sam’s Club, the club retailer owned and operated by Wal-Mart, is stepping up its sourcing of local produce, grocery and non-food items. The chain recently began hiring regional managers tasked with buying more local and organic products in categories such as salsa and craft beer. Managers also are encouraged to seek out promising new products for inclusion in sampling programs and in special displays of unique and local brands, known as “Road Shows” that travel from store to store.

“It is not unusual for our club managers to meet a local entrepreneur with an incredible product and share their information back to our Road Show team to look at the opportunity to test their products in our club,” Todd Matherly, senior vice president of dry grocery and beverage at Sam’s Club, told Food Dive in an email.

Retailers that don’t have the staff or the money to seek out local suppliers are increasingly looking to third-party companies to handle the vetting and distribution for them. These include aggregators and food hubs regulated by the U.S. Agriculture Department that gather products from numerous local suppliers and prepare them for delivery on the large scale accustomed to by supermarkets.

Good Natured Family Farms in Bronson, KS, sources eggs, produce, meat and other goods from small farmers located within a 100-mile radius of Kansas City to local Hen House Market and Price Chopper stores. Cherry Capital Foods, a local hub that gathers and distributes food grown and manufactured in Michigan, enlists supplier members and offers product lists from which retailers can make regular orders.

“[Retailers] don’t have to have an individual relationship with all those vendors or farmers to get products, which is very inefficient for a grocer with limited margin to maintain all those relationships,” Stephanie Pierce, sales manager at Cherry Capital Foods, told Food Dive.

Cherry Capital distributes to a growing list of specialty and mainstream supermarkets in the state, including Fresh Thyme, Earth Fare, and Lucky’s Markets.

For the past five years, the company has supplied Kroger stores with a rotating supply of local products that the retailer uses to build special “Michigan Made” endcaps. Recently, Kroger began sourcing local honey from Michigan producers. Pierce said the company is interested in moving into other categories, as well.

“They’re exploring these new possibilities, whereas five years ago they were very unsure about even doing a packaged product,” she said.

Suppliers step up their game

As the interest in local sourcing builds, grocers and suppliers are turning to technology and other innovations to help them work better together. RangeMe, which works with H-E-B, Target and Sprouts, among other grocers, matches retailers with emerging brands that fit their needs. FoodHub offers buyers a database of farmers, manufacturers, brewers and other suppliers to browse and connect with.

Tech firms also are addressing what comes after the two parties have begun working together such as selecting products, paying for them and arranging delivery. One such program, Forager, provides a platform for retail buyers to view available supplies, place orders, pay and schedule store delivery with local suppliers.

According to David Stone, CEO of Forager, the platform saves buyers from having to email with suppliers at every step — a process that can add up to hours a day, depending on the number of suppliers.

“Imagine having to book airline tickets for 140 different passengers,” Stone told Food Dive.

Many young farmers are digitally savvy and prefer to use a software program to market and manage their inventory. Recently, Forager finished a pilot program in its home state of Maine that connected local suppliers with grocers, co-ops and wholesalers. Now, Stone hopes to expand the program to retailers and suppliers throughout the northeastern U.S., including mainstream grocers.

“The demand for local is taking off, but the supply is still a challenge for conventional grocers,” he said.

As retailers work to improve their local sourcing, suppliers are stepping up their branding, product quality and operations with the help of food incubators and accelerators. These outlets provide funding and prep facilities for promising companies in exchange for a stake in the company or — in the case of incubators — an hourly fee.

Portland’s KitchenCru, which opened in 2011, helps members set up a website for their product, and offers sales support through connections with local retailers. New York’s Hot Bread Kitchen and San Francisco’s La Cocina focus on assisting low-income entrepreneurs. Both have business workshops for entrepreneurs in addition to prep facilities.

In Washington, D.C., Union Kitchen operates on all three fronts of the retail industry: production, distribution and store sales. Started in 2011, the company runs a communal kitchen and business development program that gets fledgling companies making everything from cookies to cold brew coffee on their feet and working toward a retail contract. Union Kitchen also distributes products, including many that were developed in its kitchens, to more than 200 retailers in the D.C. area, including Whole Foods.

“We help these companies get on their feet, and we’re able to leverage our size to get better deals and distribution than they could otherwise get on their own,” Cullen Gilchrist, Union Kitchen’s co-founder and CEO, told Food Dive.

Two years ago, Union Kitchen decided to take the concept one step further and open a grocery store that stocked many of the products it had developed. Earlier this year, it opened another location. To attract as many customers as possible, the stores, which Gilchrist says are a throwback to the vintage corner stores of decades past, stock conventional products as well as mainstream natural and organic brands. However, Gilchrist pointed out the 200 local products — from fresh-baked pies to D.C.-brewed beer — are the main draw.