Conflicted beekeepers and invasive

plant species.

The inspiration of talking to

super-senior beekeepers.

Odds and Ends.

James E. Tew

Stay Connected

http://onetew.com

I’m conflicted about my bees and invasive plant species

I’ve tried to start this piece three or four times. I’m having trouble hooking it. I know my thoughts, but I can’t assemble the words to describe them. In fact, on earlier occasions, I have tried to write about these devilish invasive plants. I didn’t do very well writing the other pieces either, and I am already worried about the success of this one.

As a disclaimer, I’m not writing as any kind of plant or forage specialist, and I have an admitted bias in favor of bees. So, I’m writing as a typical beleaguered beekeeper with ever dwindling food resources for my bees and their uncontrollable foraging visits to undesirable plants. From that stance, it’s a bit dicey for me to stay objective, but I do try.

I confess that there are several forms of “me” all packed into my one body. These different “me forms” regularly argue amongst themselves about issues like goodness or badness of nectar producing invasive plants or logging beautiful old Oaks so I can have clear and blemish-free woodworking lumber. I want it both ways. I want beautiful forests with grand Oaks, but I also want high quality, clear boards for my furniture projects.

In a similar manner, I want the environment of my youth returned to me. There was simply more “growth” everywhere. There were more insects – both good and bad – everywhere. Weeds, grass, and sapling trees were everywhere on our farm. There was a significant quail population in Alabama, but strangely a much smaller deer herd. Now the quail population, on our family farm, is at zero so far as I can tell. At the same time, deer are nearly pests. The primary reason seems to be changes in farming practices.

I am conflicted. In the last few decades, we have become amazingly adept at destroying more “weeds” than ever before. “Oh, that’s good!” Well, it is if you hate weeds; however, weed flowers are frequently beneficial to insect pollinators, so this success at weed destruction seems bad to others including me. On one hand, applicators – both professional and homeowner – have ready access to convenient chemicals and application equipment that will kill “weeds.” That technology is not going away. We beekeepers will have to find ways to work around it.

Are we crying crocodile tears?

Now, across the country, lawns, roadsides, fence rows, and fallow fields are cleaner and neater – possibly even sterile – for insect visitors. We have the technology and an evolved human culture that has changed through the passing decades. We have commercial companies that are superb at keeping our lawns lush and weed-free. Or should that be written, lush and sterile?

Are lawn care providers a bit villainous? Nope. Our homeowner culture wants this service. It’s where we are at this point in cultural development. I suspect if masses of lawn-loving people wanted a clover-based, lush lawn, there would be clover lawn care sources that could deliver it.

Why all this rant about lawn care? Because as beekeepers, we do a similar thing. We cry crocodile tears about invasive plants that help our bees.

Invasive, nectar/pollen producing plants are seemingly in every area of the country. In some instances, beekeepers had a hand in the distribution of various invasive/exotic plants. I would argue that our involvement has been tiny compared to larger schemes that spread these unloved plants far and wide. For instance, I thought that Chinese Tallow trees were primarily distributed by beekeepers just a few decades ago. In recent times, maybe they were, but apparently, it’s on record that Ben Franklin had a hand in introducing these plants into our country in 1776. They have been here for a long time.

Though Chinese Tallow is a major invasive in many southeastern states, confusingly, it has positive uses and ornamental value. Regardless, this plant is not wanted by agencies that try to control such invasive plants. It aggressively eliminates local flora, and it’s a tough survivor. One of me does not want these trees, but another me can’t help but notice honey crops beekeepers get from these plants. Isn’t it interesting that you can easily purchase this plant on the web? Piece of cake. One group hates them while another group sends them across the country.

Plants such as Autumn Olive, (primarily nectar and blooms April-June), Purple Loosestrife (nectar and pollen, essentially blooms July-September), and Chinese Tallow tree (primarily nectar and blooms from April-June) provide sustenance for our bees at a time when vast amounts of other sources have been destroyed for agricultural and cosmetic reasons. Contorted reasoning is the current result. Society does not want either weeds or invasive plant species, but that same concerned society does want bees everywhere to thrive. Prithee from where? If we could get back to our industry high colony numbers back (about 5.7 million), they would very nearly starve to death in this changed environment.

You see? I have finished where I always do.

New beekeepers, we are faced with a conundrum. All the old beekeepers already know the situation. I do not want the general environment mightily altered by these plant squatters. Birds, fish, other aquatic systems, plant diversity, and wildlife are negatively affected by these invaders. But, these undesired plants are out there – and have been out there for many years – bribing our pollinators with tantalizing food rewards, rewards our bees can no longer get from destroyed weed species. Much like punishing the entire class for the malfeasance of a single student, neither can we withhold pollination activities from all plants in an effort to harass invasive plants.

Probably to the annoyance of other groups, my only option – I cannot speak for all you readers – is for me not to propagate these plants in any way. I will not order or transplant. I will not nurture them. Indeed, on my parent’s property, I have worked for years to eradicate Chinese Tallow that I initiated there 25 years ago. It wasn’t wrong then. I had Dad’s three acres completely free of Tallow, but my brothers and I have since sold the property. The Tallow tree seeds on that property will begin its recovery in just a few months as spring arrives. They will have won those three acres back.

But I cannot speak for my bees. They will be out there searching for food anywhere and everywhere. They will not differentiate between good and bad plants as it concerns invasives. That’s what they do – they pollinate. Please remember that it is not just our honey bees. Many insect pollinators visit these plants. Somebody needs to do something about invaders of this type, but I am not sure it will be beekeepers. What’s your opinion?

The inspiration of chatting with super-senior beekeepers

There are still a few beekeepers in the southeastern U.S. who can remember apiaries like this. I came in at the “bottom of the ninth.” I only remember a single box hive apiary and brother and I destroyed it to “make it modern.”

There’s no smokers involved–no suiting up. Indeed, there is rarely – if ever-any bees, but there certainly was at one time. These beekeepers who are in their upper eighties or anywhere in their nineties are the ones to which I am referring. These people are tough and genuine. They have lost friends and family, but they have survived to this point. Frequently, they do not live in their original home.

To them, most bee things are memories. There is little concern over anything Varroa or any other current bee problem. Their bee world is the accumulated memories of a lifetime of youthful beekeeping exploits that happened oh so long ago. As it were, their bee contributions are amber, pleasant memories. They do not offer to help in your apiary. They only want you to listen as they talk of their bee days.

Like a good story, these people remember beekeeping before it morphed into the modern procedures of today. There was very little plastic anywhere in beekeeping during this time (older beekeepers seem to be mostly male in my experience) and protective clothing was very nearly primitive. There were rewarding honey crops during most seasons and swarms were disgustingly plentiful. Queens were cheap and readily available. Southern states like Alabama and Mississippi had small sized queen producers across the state. Hauling bees on a 1943 flatbed Chevy with a 6-volt headlight system provided stories and memories.

These beekeepers “lined” bees for real need and not just pleasure. Like coon dogs, the kids who are now super-seniors were sent across hills and dales to chase bees, not raccoons. Dad, the long-passed beekeeper would operate the lining box. The beekeeping family would move as a predatory group “following the bees.” When the tree was found, ideally it would be cut down and the “gum” carried home (on the 43 flatbed).

These bee gum keepers would improve their operation by building box hives; a change that was then considered to be moving up. Today, there are hive versions that, in some ways, approximate these box hives by allowing bees to build free comb.

Yes, beekeeping had already moved beyond this phase if you had the money and accessibility. Early versions of modern equipment were available. Many of these early keepers were only doing what their beekeeping parents had done. The procedures did not need updating. I treasure these rare conversations, and today you and I stand on their shoulders.

Odds and Ends

Novel insulation board use

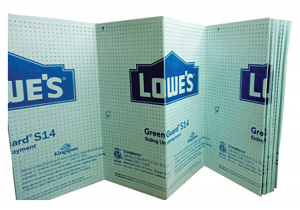

This is not the exact product that was used, but this photo should help you get to the right department. It’s thin at ¼ to 3/8 ’s of an inch – depending on the product.

Last evening, Eric M., an Ohio beekeeper told me that he has had good luck in the past few winters using thin insulation board that he purchased at Lowes. The product is available at most home improvement businesses.

He described a product that is sold in smaller sizes than what I have pictured below, but importantly, the insulation product is folded three times and put beneath the outer cover. He has had no trouble with moisture. He hypothesizes that the individual sheets – folded on each other – mitigate the effects of a warm surface (inside the colony) being directly positioned above a cold surface, and thereby, reduces condensation. The temperature change is not as abrupt. He also has an upper entrance in the foam board.

This procedure has not been tested in all wintering areas of the U.S., but it’s simple, readily available, not particularly expensive and seems to be working for this beekeeper.

Can this gadget be a swarm basket?

This idea is completely unbaked and not even remotely near a stove. As I was on a forced march with my adult family through a new Ikea in Columbus, Ohio, I saw a collapsible round basket or tote or whatever. In the store, they were storing athletic equipment in it. Another display showed soiled clothing being held in the basket. I immediately saw a swarm transfer basket. (Truly, it was something interesting for me to evaluate rather than looking at more bathroom fixtures.)

- The “swarm basket” collapsed.

- The “swarm basket” sprung open.

The open basket is about 17” tall and 18” diameter. The bottom does not open. My hypothetical idea for swarm capture is to shake the bees in the basket. Get as many as I can. I plan to tinker with leaving the closed basket near the swarm to attract some of the strays to the outside of the basket.

Puzzlements & Possibilities

- Will the exterior bees stay on the basket during the ride home and not roam around in my vehicle?

- The top screen closes just – okay – at best. There is a plastic rim that encircles the top. I was able to fold that over the top screen circumference to close it snugly. If none of this works, I could (hypothetically) just flip the basket bottom-side-up, and transport that way.

- When I get to my apiary and wish to get the bees out – just shake them? Will they cling to the screening?

- While confined, rather than forming a cluster, I expect the bees to cling to the side and top of the basket. Will that be helpful (if the bees do that) in finding the queen?

- How long can the bees stay confined to the basket? No idea. How would I feed the confined bees if I held them for a while – say while rainy weather passed? I don’t know, but I do think there are possibilities.

- Could I use this gadget to introduce queens? Maybe put a pound or two of queenless bees in the basket. Leave them for a day or so. Confuse them. Shake them. Then drop a queen in the midst of the confusion. I have introduced queens in ways similar to this hypothetical method many years ago. No idea if it will work.

- If all fails, I will use the basket to store my bee suits – minus smoker and hive tool.

Wow! I did a quick web search and folding baskets are everywhere – but none have tops that I could quickly find. I went to Ikea and the basket was right there. My key descriptors were: Ikea and FYLLEN (Ikea’s product designation). It costs $8.00 plus shipping. But you need to know, and I really hope you understand this – I have NEVER used this basket for purposes I just discussed. Most likely you would be premature to buy it – unless you also want to tinker with it. I am simply playing with my bees.

Thanks for getting to this point

Well, if you are at this point, you may have just wasted about 30 minutes, but thanks for reading. No matter what you are told, for most cold-season beekeepers the months of December, January, and much of February are a bit bee-boring. Things like the untested basket discussion presented above keeps me engaged while my bees are dealing with Winter. Thanks for reading.

Dr. James E. Tew, State Specialist, Beekeeping, The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Auburn University; Emeritus Faculty, The Ohio State University. Tewbee2@gmail.com; http://www.onetew.com; One Tew Bee RSS Feed (www.onetew.com/feed/); http://www.facebook.com/tewbee2; @onetewbee Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/onetewbee/videos