Author: Ross Conrad

This past year marked the 50th anniversary of the first humans landing on the moon as part of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Apollo 11 lunar mission. You may have noticed there was lots of media coverage and special events focused around this anniversary here in the U.S. President Trump has even directed

NASA to send people back to the lunar surface by 2024 and establish a sustainable long-term presence on and around Earth’s nearest neighbor by 2028. Rather than being an end in itself; the ambitious moon program, which NASA has named Artemis, will help the agency prepare for a journey to an even more challenging destination: Mars. The agency hopes to leave human footprints on the red planet within the next 20 years. While no plans have been announced to include honey bees or beekeepers in this latest space program, honey bees have had their share of space flight.

Maiden Voyage

Maiden Voyage

While there have been space missions that have included carpenter bees (2003) and leafcutter bees (2018), the honey bee was the first bee in space although their maiden voyage could not be termed very successful. The honey bee’s first space mission (STS-3) took place on the space shuttle Columbia March 22-30, 1982. The bee mission was part of a Shuttle Student Involvement Program (SSIP) sponsored jointly by the National Science Teacher’s Association (NSTA) and NASA. The program gives students in U.S. secondary schools the opportunity to propose experiments for flight on space missions. Bees for the study were supplied by Coplin Bee Farms in Arcadia, Texas. The results were published in a report authored by Todd Nelson and James Peterson titled, Insect Flight Observation at Zero Gravity.

The study on insect flight motion looked at the flight patterns of honey bees, velvetbean caterpillar moths and houseflies in micro-gravity. The flies and moths that were effectively “born” in space during the mission moved around easily in microgravity, pushing off of surfaces and gliding without beating their wings. In contrast, the adult moths and bees had trouble adapting. The moths flapped their wings rapidly and tumbled chaotically in the air. The bees avoided flying and preferred to cling to the inner walls of their box. When they lost their grip, they floated helplessly.

The importance of nutrition

The feeders used during the space mission consisted of Teflon tubes with a wicking material soaking in the food syrup inside. Officials speculated that this type of feeder, which had to serve all three insect types, may not have been practical for honey bees based on the fact that all 14 bees that went up in the orbiter died in their flight box apparently from insignificant nutrition.

The final report noted: “The 14 bees aboard STS-3 were observed to walk only on the screen surfaces inside the flight box. They appeared to be unable to cling to the smooth plastic surfaces. Brief attempts at flight resulted in unstable paths, tumbling about their body axes, and floating with little or no wingbeat. Floating was observed for long durations and appeared to be a result of inability to cling to a smooth surface when they came into contact with it (with wingbeat ceasing at contact). The lack of relative-motion visual stimuli necessary to maintain flight may also have been responsible for the floating responses of the bees. In addition, it may have been that the food supply provided was inadequate for the bees and this may have led to fatigue with resulting poor flight control responses and floating.”

The paper further states: “Comparisons of the zero-g flight responses of the three species of insects suggest that the flies were most able to control their flight and body orientations. The moths appeared to be somewhat poorer at controlling their flight and body orientations than the flies. The bees appeared to be unable to control their flight in zero-g conditions and they were observed to mostly float about randomly in the flight box.”

Following the space mission, Dr. Shim Shimanuki of the USDA Bioenvironmental Bee Lab in Beltsville, Maryland examined four bees (two from the 0-g box and two from the 1-g box) sent to him by Mr. Mel Coplin. Shimanuki found that the 0-g bees were free of any known bee diseases. He also found that the sugar solution used for feeding the insects was too dilute to sustain the bees over a nine-day period.

Mission Success

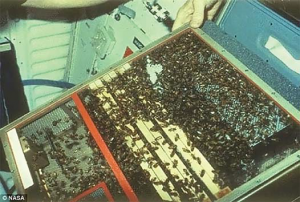

In 1984 NASA sent bees up in the space shuttle Discovery also as part of a SSIP study. The mission STS-41C (originally numbered STS-13) was to monitor honey bee behavior and survival, and compare honey comb constructed in micro-gravity (1-g and 0-g) with comb built on earth.

In keeping with NASA’s love of acronyms, the bees were kept in an aluminum BEM (Bee Enclosure Module) constructed with a Lexan top to facilitate visual inspections and photography. The BEM included “a feeder trough, three wooden honeycomb frames, a small flight chamber, a ventilation hole, a fan and two temperature probes.” The BEM also contained a filtration system to address concerns that dead bees and bee by-products might create hazards for the human crew.

Since the only insects to occupy the BEM during the mission were honey bees, the feeder could be designed for the bee’s needs in mind. It has been found that micro-gravity can cause liquids to bead up into free-floating droplets that are fairly useless to the bees and potentially hazardous to the crew. As a result the feeder in the BEM was filled with a mixture of standard sugar syrup mixed with agar in order to create a semi-solid consistency to the feed.

Crew members observed the orbiting bees four times during the eight-day mission.

- April 6 (9 hours after launch) – Bees survived launch.

- April 9 – Video recordings and observations of bees and their behavior. Some bees attempted brief flights, colliding with the chamber walls.

- April 11 – Additional video recordings of bees and their behavior.

- April 13 – Final visual observations. Flight patterns show complete adaptation to microgravity.

The scientific paper on the mission published in the journal Apidologie (1985) noted: “Worker bees were observed crawling on the sugar syrup mixture and feeding directly from it. The bees were observed fanning their wings in a group near the air inlet. Other clusters of bees extended from the sugar source to the area of active comb construction. Dead bees were removed from the cluster by other workers and deposited in the fan area.”

The space bees survived well and of the roughly 3,400 worker bees and caged queen in the BEM, only 120 died during the course of the space flight. About 35 eggs were found in the BEM following the bee’s time in space but for unknown reasons these eggs failed to hatch when transferred into a hive on terra firma.

The Bee Enclosure Module (BEM) that protected the bees from the human crew during their flight into space.

Beeswax space station

The bees built comb both naturally and from a base of foundation. The average diameter of honey comb cells were smaller and wall thickness greater for comb built in space compared to that built on earth. For two pieces of comb the bees built during the mission, all of the cells on any one side of the comb had angles in the same plane. One comb built by the bees had cells on one side that were angled up toward the Lexan top. On the other side they were angled down toward the BEM floor. However, a piece of comb that was built up from the BEM floor “displayed a wide range of angles.” This indicates that the bees were potentially having a difficult time differentiating up from down without the benefit of gravity. It was speculated that since the bees used on the space flight were all about 15 days old, prior learning from pre-flight comb building activity may have played a role in comb construction.

When it came to bee-powered space flight, the honey bees seemed to exhibit a remarkable ability to learn and adapt to conditions in space, especially when one considers the that unlike the human crew got a lot of training before-hand, the bees got no training. “Bees were observed to engage in short flights: on 9 April some bees collided with the walls of the chamber, but on 13 April bees engaging in directed flights avoided such collisions. The crew noted in the log book that ‘. . . by Day seven comb well developed, bees seemed to adapt to 0-g pretty well. No longer trying to fly against top of box. Many actually fly from place to place.’”

Conditions in space are so different from those on earth that such missions are academic exercises – interesting in and of themselves, but ultimately providing little to no practical value for earth-bound beekeepers. And as for us humans, a strong argument can be made that we have no business going to other planets until we learn to take care of the one we already occupy.