A Review of the Manitoba Beekeeper’s Association Annual Conference

By: James Masucci

A cold, February sunrise in Winnipeg. The backdrop of the annual Manitoba Beekeeper’s Association conference.

Why would any sane person leave their home on a rare, 70 degree February morning and travel to Winnipeg where the highs are zero degrees Fahrenheit? Yes, beekeepers are crazy, but I had a good reason. I was invited to present some mite control data to the Manitoba Beekeeper’s Association at their annual conference. I had done this before, about five years ago, and this remains one of my favorite beekeeping meetings. The two-day meeting is a relatively small gathering of commercial beekeepers, the provincial Apiarist, provincial Ag officials, members of the Canadian Honey Council and honey bee researchers. All the necessary people to dig into the state of the industry.

The agenda of the meeting was driven by the horrible mortality rates that Canada, in general, and Manitoba, in particular, experienced over the 2021-2022 Winter. Mortality rates for the whole of Canada were around 47% and in Manitoba were over 60%. This is for a province that averaged 20% or less mortality for the last eight years or so. Discussions with beekeepers and the report from Derek Micholson, the provincial apiarist, indicate that these losses were caused by the “usual” suspects. A drought in 2021 impacted nutrition, mites and nosema brought disease and weather extended the Winter up to two months beyond their normal extended cold. It’s one thing getting your bees through six months of Winter, but try extending that to eight months. One beekeeper told me how he took his bees out of Winter storage for about a week and had to put them back in due to back to back weather fronts that came. In general, the talks/discussion can be classified into two topics: how to get better queens and how to reduce colony stressors. The latter category was heavily focused on varroa.

Pests, Pathogens and Other Stressors

The tone of the meeting was set with the first talk, Industrial Bees – Is High Density Beekeeping Bad for Bee Health. This was a talk presented by Lewis Bartlett from the University of Georgia and gets to the key question, “are commercial beekeepers shooting themselves in the foot by having large apiaries?” Lewis is akin to a honey bee epidemiologist and his data indicated the answer is “no.” In fact, managed colonies are healthier, in general, than feral colonies. Basically, all bees are exposed to all diseases and there are other factors that influence the severity of the disease that you see. I asked him about the advantages of isolated apiaries and keeping diseases out. His response was that the density of hives is so high, that it’s almost impossible to have a truly isolated yard. It’s okay to place the maximum number of colonies in an area that the forage can support.

Rob Currie, professor at the University of Manitoba, presented one of the few talks on bee stressors that was free of varroa. The presentation, Virus, Pesticide and nutrition interactions in honey bees in Prairie cropping systems: Death by a thousand cuts described the work he and several other researchers did to evaluate different stressors in the cropping systems common to the prairie provinces. The study looked at bees on canola used for oil production, canola used for seed production and soybean, and compared them to colonies in the same region but away from those crops. The data represented the “tool development stage” of a more long-term attempt to understand the interaction between stressors on honey bees. Samples were taken pre-flowering, during flowering and post-flowering. Pesticide prevalence in the hives were higher during flowering and post-flowering in all three cropping systems. This same trend held for sacbrood virus and deformed wing virus in colonies on the edge of soybean fields. Interestingly, sacbrood was high at all timepoints in colonies next to canola fields and deformed wing virus started high in canola and dropped as the season progressed. It will be interesting to see how consistent these findings are and if they are able to find interactions within these cropping systems.

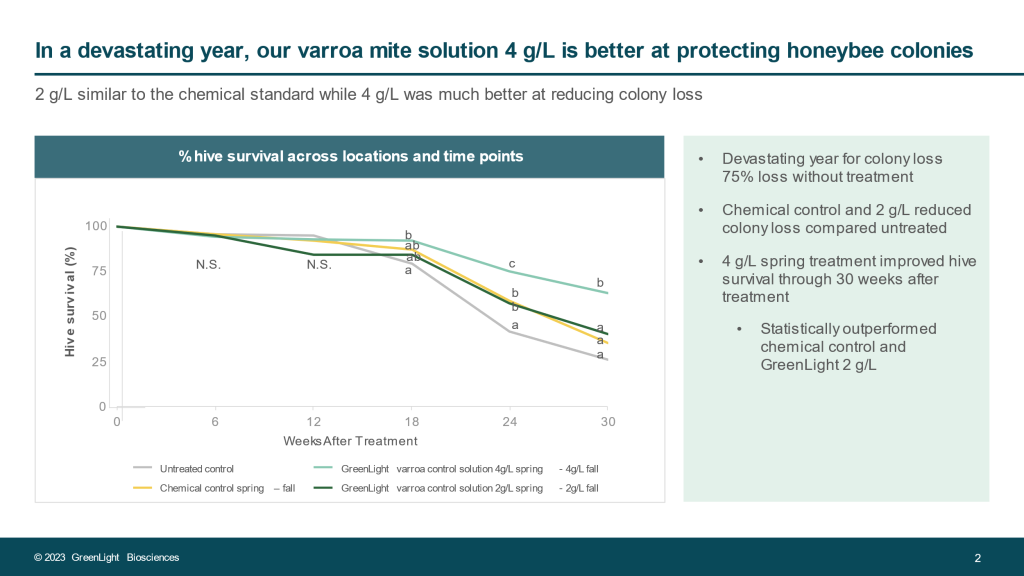

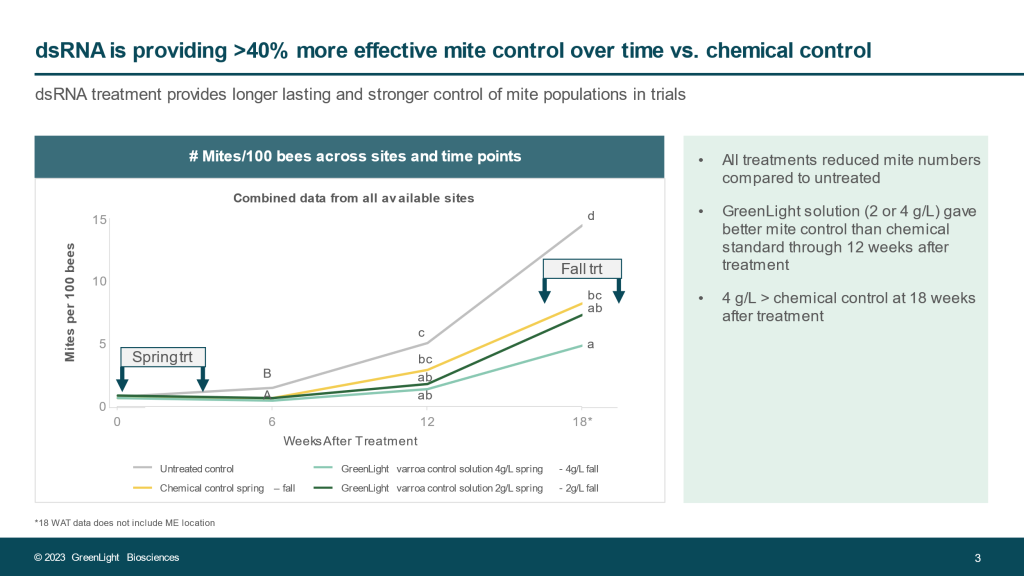

Mite control and preliminary survival data for a novel, RNA-based mite treatment being developed by Greenlight BioSciences. Assessment 1 was at the start of the trial with the chemical control treatment lasting six weeks and the vadescana treatment happening at week zero and week three. Assessments were done six weeks apart. The yellow line represents the untreated control. The red line shows mite data from hives that received a 42-day Apivar treatment at the start of the trial. The light green line shows mite data from hives treated with a high dose of vadescana. The dark green line shows mite data from hives treated the low dose formulation of vadescana.

There were several talks on varroa control. Here I must disclose a potential conflict of interest. I was one of two scientists representing Greenlight BioSciences to discuss the new varroa product they are developing. Greenlight is developing an RNA-based product, vadescana, that directly targets reproducing mites. Brian Manley showed data from several trials indicating that vadescana can keep mite levels below threshold levels for more than 12 weeks. He also showed some preliminary data from an overwintering trial where Vadescana-treated colonies had twice the survival rates as Apivar-treated colonies. The overwintering trial also showed how effective rotating modes of action (i.e. Vadescana in the Spring and Apivar in the Fall) can be for mite control and colony survival. Pending approval from the PMRA, Greenlight will be doing trials in Canada this year.

Steve Pernal, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, talked about a new miticide that he is working on. The miticide, 3C(3,6), is a plant based compound that has a similar structure to Thymol. It is not as volatile as thymol and it is not clear how much activity comes from fumigation vs topical exposure. The lack of volatility is an advantage over thymol, in that they have not seen brood kill or queen issues with 3C(3,6). Efficacy ranged from 42% in 2021 to 94% in 2022. The difference reflects product development as they are working out appropriate dosing and application methods.

Amber Leach, of Veto-Pharma, spoke on Apivar. She acknowledged that there seems to be pockets of amitraz (the active ingredient in Apivar strips) resistance and talked about the dangers of off-label amitraz use. Following the Apivar label and rotating different miticide treatments is the best way to combat this resistance. One of the beekeepers pointed out a potential flaw in the design of the Apivar strips. When you use the tabs to keep the strip in place, one side of the strip is pinned against the frame. Thus, you are only treating with half the dose that you should be. It may be more effective to hang the strips using toothpicks, matchsticks, etc. so that both sides of the strip are accessible to the bees.

Breeding for Better Mite / Stress Resistance

Last year in Bee Culture (Bee Driven Mid-Life Crisis Part 2: What’s in a Queen? https://www.beeculture.com/bee-driven-mid-life-crisis-p2/), I talked about the difficulty of queen breeding. Uncontrolled mating and the lack of easy trait selection has resulted in very little improvement in queen quality over the years. There were a couple of presentations that showed we are making baby step improvements in our ability to breed.

Steve Pernal gave a talk entitled Colony phenotypes for breeding and insights into Winter losses. He showed the drivers for colony survival were sealed brood, colony weight and cluster size and showed that hive weight increase from 29kg to 30kg resulted in a 30% increase in probability of colony survival. He also showed that varroa and DWV levels were predictors of mortality. The critical piece to this presentation for me, was that he successfully used marker assisted breeding to increase hygienic behavior in three generations. Marker assisted breeding is where you have a molecular marker, either a protein variant or DNA variant, that is closely associated with a trait of interest. It’s a technique widely used in the rest of agriculture but lacking in honey bees. Steve has a panel of proteins (many are antenna proteins) that are related to hygienic behavior. Steve successfully used these proteins in a breeding strategy to increase hygienic behavior. He compared using no selection, marker assisted breeding and the freezing brood kill assay (liquid nitrogen). After three generations of selection, marker assisted breeding produced the highest level of hygienic behavior, followed by the freeze kill selection. To me, it just emphasizes the need for a good molecular map if we really want to breed honey bees.

In the absence of a molecular map, Kaira Wagoner, of the University of North Carolina – Greensboro, has developed an assay for hygienic behavior that appears to be better than the traditional freeze kill assay. The problem with the liquid nitrogen assay is that it kills the pupae. Therefore, it is selecting for bees to recognize dead pupae. Are the signals produced by dead pupae the same signals that are produced by sick pupae? We want hygienic behavior to target sick pupae. Kaira spent several years identifying 10 chemicals that are elevated in unhealthy bees and developed the correct ratio of these chemicals to mimic what she calls the “unhealthy bee odor” (UBO). She has developed a two-hour assay, where she sprays capped brood with UBO and counts the number of uncapped cells after two hours. She showed that 60% uncapping in this assay was enough to control mite levels. The hygienic bees (those doing the uncapping) had high virus levels, but the hygienic colonies as a whole had lower virus levels than non-hygienic colonies. The system is not perfect. New queens can only be tested after seven weeks past emergence. As with all multigenic traits, maintaining the trait will be difficult. However, the assay is relatively simple, so for people willing to put in the effort, it will be feasible to select for hygienic behavior.

Queen Quality

In the absence of true queen breeding, what can be done to increase queen quality? Medhat Nasr, working for the Saskatchewan Tech Team, assessed queens from several Saskatchewan queen producers and four queen producers from California. This is important to Canadian beekeepers because they import a lot of queens. He looked at queen size (head and thorax), nosema counts and sperm counts. On average, he found three million sperm in the Saskatchewan-made queens and 1.8 million sperm in the imported queens. To put this into perspective as to what this means, he did a back-of-the-envelope calculation. A queen produces 2,000 eggs a day and each egg induces the release of three to four sperm. Therefore, the queen needs about 1.1-1.4 million sperm per year. When the sperm runs out or gets low, you either get a drone layer or supercedure. When he showed the data for individual queens, 20-50% of the imported queens (depending on producer) had less than a million sperm, indicating they could not last a year. I asked him why he thought this was the case and he felt it was due to the mating yards being too dense without sufficient drones.

Provincial Apiarist Report

Manitoba’s beekeeping industry suffered in 2022. Over 60% losses over Winter had several effects. The number of beekeepers declined for the first time in about 15 years (from 925 to 905). The number of colonies dropped from around 115K to 103K. Honey production dropped 15-20%. The saving grace was an increase in honey prices, which greatly buffered the impact of the losses.

Manitoba’s Knowledge and Research Transfer Program (KRTP) did some testing for amitraz resistance. They used both the four hour Apiarium test and the 24 hour Pettis test. They found that amitraz efficacy ranged from 15% to 100%. There is definite evidence for pockets of amitraz resistance.

Derek also reported on the priorities of the National Industry-Government Bee Sustainability Working Group. This is a large group made up of both government and industry representatives. Their top priorities are to support the Tech Transfer Programs. These programs are in every province and they perform locally relevant, applied research as well as extension services. They are also coordinating at the national level to work on common beekeeping issues. Top priorities of the working group also include accelerating the development of new varroa control solutions, actions to maintain and increase domestic bee supplies and actions to address long-term challenges to importing bee supplies. Their secondary priorities are to improve the overwintering of queens (which will ease the need to import queens), business cost analysis of the industry and the opening of the U.S./Canada border to package bees.

Opening Up the Borders

Opening the U.S./Canada border to package bees is a hot topic. I had a few conversations with beekeepers over this. In the U.S., beekeepers in the northern states buy nucs, queens and packages from the southern states. Some beekeepers are concerned where their bees come from. For example, the bee club I belong to only orders queens from Northern California, because of a concern of bringing in Africanized bees. (I, on the other hand, get queens from TX, LA and GA). The same holds true in Canada. They need bees and queens, just like the Northern U.S. states do. But the U.S./Canada border has been closed to bee traffic since tracheal mites in the 1980s. Canada brings in bees from Australia, New Zealand, and now Italy and Ukraine. They do get some queens from HI and CA, because they have established safe zones where there are no Africanized bees within 100 miles. In CA, this safe zone was recently reduced to 50 miles due to the detection of Africanized bees within the 100-mile zone.

So, do we bring in bees from across the ocean and potentially bring in a new pest or pathogen from there? Or do we treat North America as one isolated domain and move bees within that domain knowing there are Africanized bees in the south? The Canadians worry about Africanized bees and about antibiotic resistant AFB in the states. The U.S. is worried about viruses and don’t allow the importation of Canadian queens.

The Canadian Honey Council has provided the CFIA with the data necessary to redo a risk assessment for the importation of packages from the U.S. This issue now rests with the CFIA. Whether they act on this will likely depend on the pressure they get from both Canadian beekeeping organizations and the U.S. I am sure this issue is as much political as it is biological.

What does Canadian beekeeping have to do with me?

Having attended beekeeping meetings in both countries, I realize that beekeeping is a global industry. We are all dealing with the same beekeeping issues. I’ve learned a lot about beekeeping from both Canadian colleagues and U.S. colleagues. I take the best of both worlds and apply them to my own operation. A case in point is Lloyd Harris. I bet most beekeepers in the U.S. have not heard of him. I met him about five years ago and he changed the way I think about bees. He closed out the conference with his presentation The Winter colony and its formation. The talk was based on his graduate work he did back in the 70s. He painted cohorts of newly emerged bees every 12 days throughout the year to determine their longevity. From this data he draws incredible insights into the dynamics of the hive throughout the year. Is this data still applicable and useful? Of course it is! If any of you have heard Randy Oliver or Ian Steppler talk about beekeeping, they both show a graph of the colony age distribution throughout the year. It’s Lloyd’s graph. It doesn’t matter how long ago or where he did the study. We have a lot to learn from each other.

One aspect of the Canadian industry that I really like is how closely tied the Canadian Honey Council is to the beekeeping problems of the industry. They don’t just lobby for funding and legislation but get into the weeds to help solve problems. For example, the CHC owns the registration for formic acid and Fumagillin. Currently, the CHC is working with the Ontario Tech Team to get Oxalic Acid/Glycerin strips registered. By doing this, they ensure the beekeepers get the tools they need. The path to registration is expensive and complicated. Unless you are a company with millions of dollars to invest in the product, you won’t be able to afford the registration process. And the beekeeping industry is too small for it to be an incentive to large companies. Once a company does go through the process, they need to charge a lot to recover the costs. Because the CHC owns formic acid, the beekeepers can mix their own treatments (probably a double-edged sword), and likely, will make their own OA strips as well. I wish our beekeeping organizations took a similar approach.

To go even further, wouldn’t it be nice if there was international cooperation between our beekeeping organizations in this regard? Registration packages are relatively similar in various countries. By sharing resources and costs, a path can open for special cases; emergency needs, individual discoveries, etc. We wouldn’t have to be dependent on Randy Oliver doing all the work himself or we wouldn’t have to worry if Steve Pernal’s product would ever get registered because he doesn’t have the funds. I think there is an opportunity here. We can get a lot more done by working together on common problems.