By: Kim Flottum

Acutally, It’s All About Honey

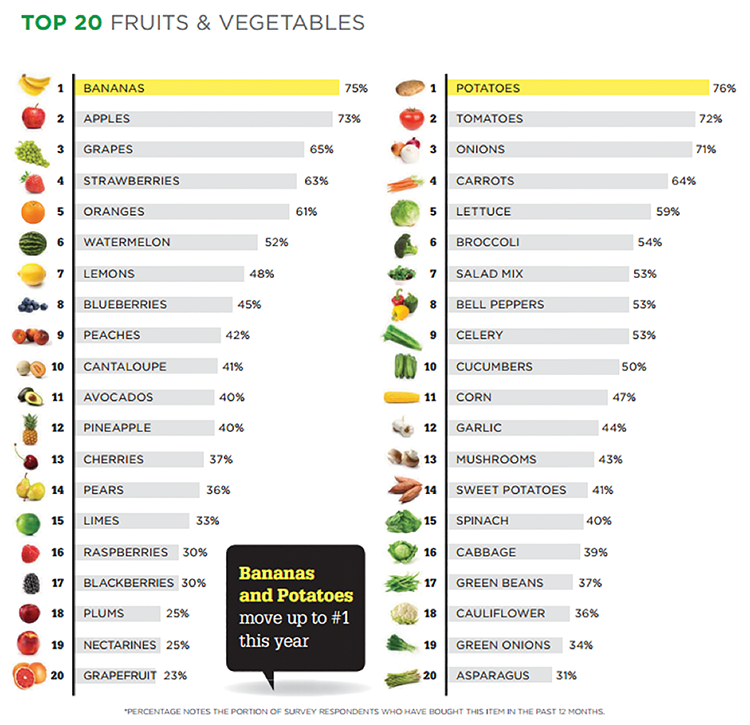

A while ago I was talking about where food comes from and Mexico is certainly one of the places a lot of our food comes from. In 2016 fruit and veggie imports from there were right at 10 million metric tons, with a value of $12.4 billion. That comes to 43% of our fruit and veggie imports and 54% of our other ag imports. When you look at what actually comes in, more than 50% of the bell peppers, limes, mangoes, pineapples, papayas, asparagus, avocados, kiwi, artichokes, blackberries, garlic, cukes, squash, bananas, blue berries, tomatoes and eggplant that we eat comes from there. Now, look at the info graphic below on what people buy, and where the fruit and veggies on this list, fall on that list.

It’s pretty obvious that there has to be bees in Mexico to produce what they do, so they can export all that food to the U.S. And there are bees in Mexico. In fact, Mexico is the sixth largest honey producer in the world. In 2015 they exported 61,801 tons of honey, mostly to Germany, the U.S., the UK and Saudi Arabia, worth just over $100 million. Their 42,000 beekeepers run 1.9 million colonies. In 2017 we imported 2.3 million pounds of honey from Mexico, out of a total of 447.6 million pounds from all countries (Mexico is only 0.5% of that total), and so far in 2018, as of May, we have imported 1.96 million pounds from Mexico out of a total from all countries of 142.9 million pounds. Clearly, they are a small player in our honey import market. But their 1.92 million colonies, compared to our 2.8 million or so means they have right about 70% of the colonies we do, and they don’t have an almond crop to pollinate – so – it must be all the other crops they have that their bees are pollinating. So, with about 70% of our bees, they are producing about 50% of the food we are importing from all countries.

But aren’t Africanized bees the dominant bee in Mexico? Yes, apparently so, but also apparently so are that the opinions of the beekeepers there are mixed about this. Some, reasonably, don’t like working with aggressive bees, while others claim that AHB are far more efficient pollinators than the more docile European bees since they forage more often, earlier and later, and at greater distances than those tamer bees. From all reports, the arrival of AHB does not appear to have had any impact on crop yields in Mexico.

Well, this isn’t about Mexico, its beekeepers or the food they export to us. What this is really about is the fact that we continue to hear the “every third bite, bees are disappearing, end of the world” claims made by just about everybody.

Although the “every third bite” may be true (I haven’t really examined that statement), it is true that every third bite doesn’t come from the U.S., nor is it pollinated by U.S. honey bees. With only a few exceptions, not a whole lot of what we eat is pollinated by U.S. honey bees. Some, absolutely, yes, no question, and growers are glad they are available. But are they willing to pay what they apparently are worth? The complaint there is that they, too, have unfair import competition so the prices for pollination they can afford have to stay low. The other half of that story is that beekeepers, after almonds, need a place to go until the snow back home melts so why not give free (or nearly free) pollination to some post-almond crop growers and both benefit from the opportunity.

There is no doubt that keeping bees is more expensive than it was 50 years ago, but bees in beehives are not disappearing. If you look carefully at the USDA NASS Colonies report analyzed in this issue, it’s plain to see that the number of colonies of bees managed by beekeepers has remained relatively constant for the last three years, with normal, expected quarterly changes to accommodate pollination contracts, sales of bees, and wintering schedules. Yes, individual colonies and even whole operations sometimes collapse, but our industry has not collapsed. The numbers show it hasn’t. And, when you look at replacing those colonies that are lost, about half are replaced each year with bees from the same outfit, and only about half are actually new bees. This has been the story of lost hives since bees have been in boxes. The numbers show that beekeepers are using more colonies for pollination every season, producing more bees to build on their own business and to sell to other beekeepers every season and putting their energy, time and resources into producing profitable products, rather than unprofitable honey.

U.S. beekeepers have adapted to the fact that the U.S. does not value U.S. honey, primarily because of the price. Rather, U.S. buyers, at all levels, have put price first. Quality? Sometimes.

How little do they value U.S. honey? From the July USDA AMS National Honey Report, honey coming in from Argentina was being bought for between $1.28 and $1.39, from Brazil $2.17 for orange blossom and $1.66 – $1.95 for organic, from Brazil $0.87 to $1.01 and Vietnam from $0.85 – $1.14. Canada honey was at $1.40. Across all colors and kinds of US honey, the average price was $2.03, with a range of $1.65 – $2.75. All this was in volumes of 10,000 pounds or greater. There is no doubt honey is a commodity.

So rather than butt heads with the cheap labor markets and questionable quality of honey from Vietnam, India and Brazil (Mexican honey sells in the U.S. at the same, and often higher prices than U.S. honey because much of it is organic), U.S. beekeepers are producing products that produce profits.

Think about this. I can pollinate one, maybe a few crops in the spring, which puts a stress on my bees, and money in the bank early, and that’s a given. Plowing a field puts stress on a farmer’s tractor, keeping chickens in a coop and pen is more stressful on the chicken than free range, tiny farrowing pens are more stressful on sowing pigs than wide open spaces, and simply harvesting honey is more stressful on a colony than letting them have it all. But all these things put money in the bank. Some managed stresses are part of living for livestock.

So when I’m done pollinating, I can move by bees (another stress) to a location, hopefully free of agricultural chemicals (another stress), and with enough forage to last the season. There, my bees can forage, raise kids, live life to its fullest. I can, in the meantime, make the choice to manage those bees to make as much honey as possible, which I can later sell for something like $2.50/lb in a barrel to a packer, broker or whoever later in the season. Or, I can manage those bees to simply make bees, which they are going to do anyway, using the honey I would have harvested. So, how much did you pay for that three pound package last spring – something like $150?

So I can make honey for $2.50 a pound, or I can make bees for $50 a pound, have more than enough bees to pollinate next spring because I know some won’t make it through the winter and the ongoing stress of moving a couple of times, and do it again next spring. And still be in business.

So, losses. And recovery. And numbers of colonies. Losses are somewhat higher, overall, than before Varroa, but recovery rates not only make up but exceed losses, and numbers of colonies are steady. Keeping bees is different, certainly. But the world has not ended.

Look at the numbers.

•

It’s National Honey Month. Did you forget? Honey has been kind of lost the past few years. The National Honey Board does a good job of getting the word out all year long, but the popular press is more interested in the “Every Third Bite” story about bees and beekeeping (The “If it bleeds it leads” editorial philosophy hasn’t died, you know). And anyway, eight out of every ten bites of honey that get eaten in the U.S. come from off shore, so why get all excited about promoting Ukraine honey?

And that’s too bad. The honey we harvested this year is some of the best we’ve had in a long time. There was a great locust flow early, and that was followed by an even better basswood flow, and right now the goldenrod smell in the backyard is so thick you can cut it with a hive tool. What a wonderful fragrance. A long time friend used to say the smell of goldenrod honey curing was the smell of money. He was right. He’s still right.

Local honey is still a money maker. You won’t sell barrels of it, but you can sell cases of it because the buyer knows you, knows your bees, knows your honey and knows your honey is good. Not as good as mine, mind you, but pretty good all the same.

Put a big “Local Honey” sign on your farm market stand, on your label, just in your yard, so people know where to look, where to get good, local honey, from bees that are doing just fine, thank you.