By: Ross Conrad

Made Possible by Samantha Alger and Alex Burnham

The massive increase in U.S. honey bee colony losses in the last decade has prompted a comprehensive examination of colony health in apiaries throughout the United States. Known as the National Honey Bee Survey (NHBS), the effort is a collaboration between the USDA Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service (APHIS), the Bee Informed Partnership (BIP) out of the University of Maryland (UMD), the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and the cooperation of 40 states, two territories (Puerto Rico and Guam), and the island nation of Grenada.

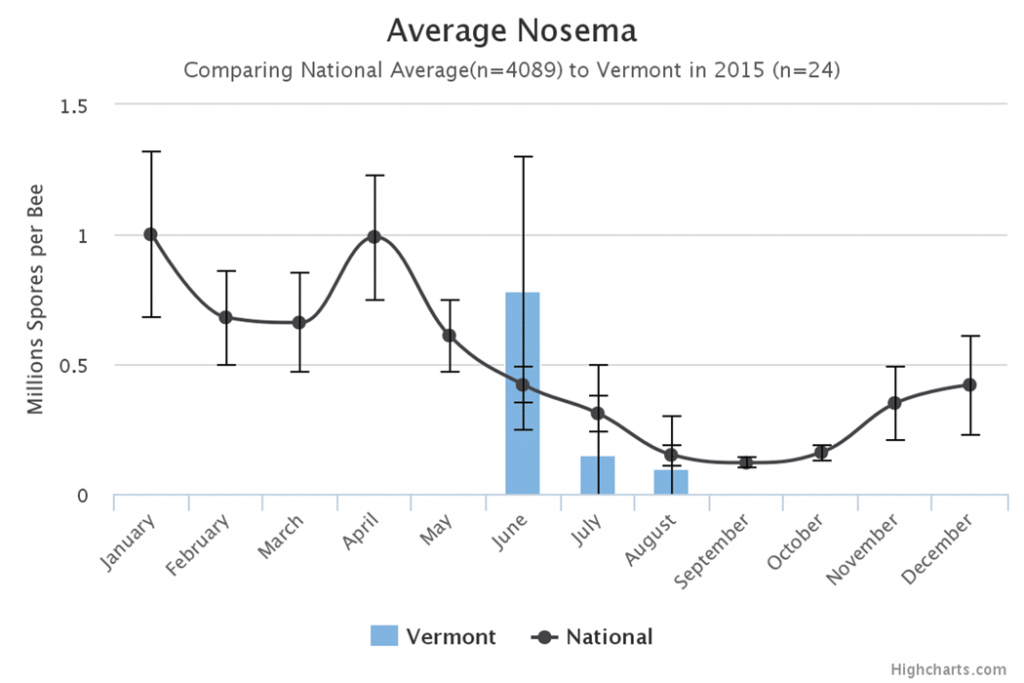

The NHBS began in 2009 in the states of California, Florida and Hawaii. In 2010, the survey expanded to include a total of 13 states as funding for the survey increased. The survey then grew to 34 states in 2011, shrunk to 32 states in both 2012 and 2013, 28 states in 2014, and grew again to 37 states in 2015, before hitting an historic high of 40 states in 2016. This effort establishes a baseline health measure for honey bees in the United States through the creation of a large and comprehensive honey bee disease, pest, (and as of 2016) pesticide residue database.

The survey has verified the absence of potentially invasive and harmful honey bee pests and pathogens within the United States such as the parasitic mite Tropilaelaps spp., the Asian honey bee Apis cerana, and slow bee paralysis virus (SBPV). Confirming the continued absence of these exotic pests and pathogens is the primary objective of the NHBS.

Since the NHBS provides a relatively quick method to detect such pests and diseases should they enter the U.S. it may be used to facilitate efforts to prevent their expansion in America should they be discovered.

The survey has also provided the opportunity to document the incidence of known honey bee diseases in the U.S. These baseline data, including historic data from research institutions such as the ARS and other ongoing field sampling and management surveys, have been incorporated into a single database as part of the Bee Informed Partnership (https://beeinformed.org/).

Each state submits 24 samples which are collected from apiaries (stationary, migratory and queen breeding) across each state and territory, with 48 collected in California (24 from stationary apiaries and 24 from migratory apiaries). A minimum of eight hives are sampled in each apiary, and each apiary sampled must contain at least 10 hives.

The survey includes a visual inspection of the colonies prior to sampling. The presence of pests or diseases are recorded and entered into both the BIP database and the U.S. National Agricultural Pest Information System (NAPIS) database although they are not included in the final analysis. This is because visual identification of the following diseases and pests are dependent on the training and experience of the sampling personnel, and therefore they are not included in the Reports:

- American Foul Brood

- Black Shiny Bees

- Chalkbrood

- Deformed Wing Virus

- European Foul Brood

- Idiopathic Brood Disease Syndrome (IBDS) Sac Brood

- Small Hive Beetle Adults

- Small Hive Beetle Larvae

- Wax Moth Adults

- Wax Moth Larvae

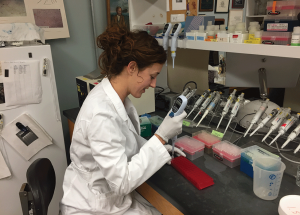

Folks at the UMD send out the sampling kits and each state is responsible for collecting the samples and mailing them in for testing. A critical component of the NHBS at the state level are the people who carry out the sampling. It is primarily this lack of sampling help that is the reason the states of Arkansas, Kansas, Maine, Missouri, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Ohio, Rhode Island, Oklahoma, and Wyoming do not participate in the survey. The state of Vermont would be on this list of non-participating states if not for the efforts of PhD candidate, Samantha Alger, and PhD student, Alex Burnham, both of whom attend the University of Vermont. Samantha spearheaded Vermont’s involvement with the survey in 2015. For the past two years she and Alex have worked together to both coordinate the survey and collect samples for Vermont. They plan to continue with the NHBS in 2017.

Assisting Vermont beekeepers in participating in the NHBS came naturally to both Samantha and Alex. Alex began beekeeping as a child, working in his grandfather’s apiary in southern Vermont. Samantha began beekeeping and learned to rear hygienic queens during a winter she spent in Hawaii. Now, as graduate students, they are both deeply involved in research aimed at understanding the threat of disease to both our managed and native bees. Samantha’s PhD dissertation focuses on the prevalence, effects and transmission of RNA viruses in bumble bees. In order to understand if Vermont’s bumble bees are contracting the same viruses affecting honey bees, Samantha and Alex conducted a field survey of RNA viruses in Vermont bumble bees and for the first time in Vermont, confirmed the presence of at least two viruses in Vermont’s bumble bees. While more work needs to be done to understand how bumble bees are affected by these viruses, this work is timely and relevant. In the same year of the survey, three bumble bee species were listed as either state endangered or state threatened. Understanding how these ‘so-called’ honey bee viruses are transmitted and affecting bumble bees is critical to the conservation of these important crop pollinators.

It was this survey that found that the Rusty Patch Bumble Bee that had been very common in Vermont in 2000, had apparently disappeared from the state by 2015. This study of Vermont pollinator populations was part of the research and data that the U.S. EPA referred to when they made the decision to add the Rusty Patch Bumble Bee to the Endangered Species list.

In 2016, Alex and Samantha conducted an experiment to test if viruses can be transmitted between bee species through shared floral resources. They grew plants in green houses and allowed honey bees infected with virus to forage on the flowers in the enclosure. They later allowed virus-free bumble bees to forage on the same blossoms to see if the bumble bees would become infected with the honey bee pathogens. So far, the pair confirmed that honey bee viruses are left behind on flowers as bees forage. More lab work needs to be done to test if bumble bees can later become infected after visiting these flowers.

During Spring break in 2016, Samantha had the chance to travel to Cuba and interview beekeepers on the island. Cuban beekeepers have to deal with many of the same challenges that American beekeepers face such as Varroa mites, Small Hive Beetles, and American foulbrood. However, due to the U.S. embargo on Cuba, the island’s beekeepers use management controls to keep disease and pests in check rather than drugs and miticides. Samantha reports that while many pests and pathogens are present in Cuba, beekeepers in Cuba are not experiencing the same losses elsewhere in the world and could be one of the last countries where honey bee populations remain healthy and untouched by dramatic increases in the kinds of honey bee losses that has swept the world since the advent of Colony Collapse Disorder. Samantha suspects multiple reasons for Cuba’s healthy bees. It could be differences in Cuban management techniques or that bees, pathogens and pests on the island have reached an evolutionary equilibrium given the island’s isolation. She also believes the lack of pesticide use could play a role. Now that the embargo has been lifted, it is possible that pesticide use will increase and has the potential of affecting their honey bees. Disentangling the threats to honey bees remains a research concern. Samantha is currently collaborating with a group of UVM and Cuban researchers to learn how Cubans are maintaining healthy honey bees despite the presence of bee pests such as Varroa. She believes there will be lots to learn from Cuban beekeepers both from a management and scientific perspective.

Samantha received a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship in her second year at UVM. It provides her with a stipend for three years and an education allowance for tuition and fees. Prior to receiving the fellowship, she supported herself through a graduate teaching assistantship. While Samantha found teaching at the university level rewarding, the fellowship allows her to have the time to focus on outreach projects such as the NHBS.

Samantha is currently working with Alex, UVM post doc, Leif Richardson, and a Vermont beekeeper on a crowdfunded research project examining the role of migratory bee operations in disease spread. Specifically, the project will test the theory that migratory hives that pollinate almonds in California acquire more pathogens than their stationary counterparts. The study will also test if migratory hives will transmit disease to stationary hives upon their return to winter yarding areas. They hope this project could help provide evidence needed to increase funding to apiary inspection programs across the country, as these programs are integral for detecting diseases that may enter states through migratory operations. The beekeepers in Vermont are grateful to Samantha and Alex for their interest and commitment to bees and beekeeping.