By: Denise Ohio and Catherine Minden

We live in the foothills of the Cascades in western Washington, northeast of Seattle. While we’re not technically in the middle of nowhere, you can see the middle of nowhere from the end of our driveway.

The land is full of trees, flowering plants, and understanding neighbors – a great place for honey bees. We’ve kept hives for over 20 years, taking a break to build our straw-bale house and returning to beekeeping shortly after beekeepers began seeing devastating losses. Several years ago we started growing lavender, distilling the plants for essential oils and hydrosols we sell at local markets and gift shops. But our focus always, then and now, has been on the honey bees.

We saw what happened when Varroa destructor moved in, the initial attempts to understand and fight it, and the joy soon followed by crashing disappointment as first one, then another, then another treatment failed. It was apparent early on that there was never going to be a single way to help the bees fight the parasite and diseases the parasite brings with it. It’s going to take a slew of tactics, even after the bees bred for hygienic behavior predominate, to manage these challenges.

Still, as difficult as it can be, it doesn’t take long in the company of honey bees to realize how remarkable they are. And as devastating as Varroa has been, it doesn’t take much to realize how remarkable they are. But while I find Varroa astonishing, that doesn’t make me like them any better.

We usually treat for Varroa in early Fall but monitor throughout the season. Rarely have we needed to treat during the height of summer. (It’s happened, but it’s not typical). And while we use Mite Away Quick Strips® (MAQS) and Api Life Var®, like most beekeepers, we’re always looking for treatments that are easier on the bees (and us) that the mites won’t be able to develop resistance to.

So I had a lovely thought one afternoon in late winter: control Varroa by finding an insect that won’t harm the bees, views Varroa as a meal, and can thrive within the environment of the hive.

They work . . . but will they work for bees?

I heard about one particular beneficial insect during a Focus on Farming conference sponsored by Snohomish County in 2015 when I cornered a presenter named Alison Kutz from Sound Horticulture (http://soundhorticulture.com/) in the lunch line. Alison supplies beneficial insects to nurseries and greenhouses, and I asked if she knew of any beneficial insects that could be used against Varroa in a beehive.

Her immediate response: “Strats.”

Stratiolaelaps scimitus ‘Womersley’ (once called Hypoaspis miles) is a beneficial insect that preys on soil-dwelling pests such as fungus gnats and pupating western flower thrips. These ground-dwellers are fierce predators. They’re indigenous to many parts of the world, plentiful, easily raised in a production environment so getting them isn’t difficult, and, in addition to being used in greenhouses, are used to control pet and spider mites.

Strats will eat Varroa (see it in action at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rcVbtplV9oQ or http://www.niagarabeeway.com/Varroa-mite.html) and aren’t interested in honey bees as food at any stage of the bees’ life cycle. However, it appears they only go after phoretic mites so we can’t count on them to go into brood cells. And even if Strats are eager Varroa predators, there are three things about them that could make them totally impractical as an effective Varroa treatment.

First, Strats live in the top half-inch of the soil, so it may require multiple applications over the season or another piece of equipment or application method to keep them in the hive. Second, they’re expensive. More about that in a minute. Third, and most important, we knew there had been some studies regarding Strats and honey bees. One in particular had been pretty unambiguous that Strats were not effective against Varroa (Sagili 2014). Another study suggested that predators like Strats were probably not going to be as effective as fungi or bacteria but didn’t completely rule them out as a possible ally in the fight (Chandler et al. 2010).

We decided to try for ourselves.

The adventure begins

2016 was an expansion year for our apiary. We wanted to boost the number of hives beyond our own splits, so we purchased 15 packages. We have had mixed results from various package providers. One year, a local provider of “hygienic” stock sold us packages of bees so infested with Varroa that we could see them on the adult bees. The parasites looked like disgusting little fanny packs, which is redundant. We got those hives healthy but were then hit with a drought and dearth. That was a fun year.

This year we bought from another recommended provider of “hygienic” bees. This time, several of the queens were poor performers from the get-go, but they were still better than the two who were just plain dead.

We replaced these queens with VSH stock and noticed that the offspring of these queens seemed more hygienic, though there didn’t seem to be a difference with temperament or productivity compared with those of previous queens, excluding the dead ones, who were neither terribly productive nor hygienic, though they were very calm.

All the package hives were installed in western supers (we use westerns for brood boxes and honey supers) and fed 1:1 syrup with Fumigilin. We continued giving 1:1 syrup with Pro Health until the honey flow began.

We selected 10 of the new package hives for our Strat test.

Five hives, C3, C4, C5, C6, and C8, were our controls. They received no treatment until the end of the season. Hives C11, C12, C13, C14, and C15 received regular applications of 200ml of Strats in media, purchased from local suppliers every four to six weeks through the season.

We bought 1-liter containers containing about 25,000 Strats in media. The cost per liter with shipping and handling was about $42.00, and 1 liter was divided among five hives. We applied Strats five times throughout the season from 14 May through 9 September 2016. The total cost for the Strat application was $210.00, or $42.00 per hive. (In comparison, a MAQS treatment costs about $4.40 per hive.)

Hives were monitored for Varroa using sticky boards and alcohol wash (Oliver 2013). Over the course of the test period, all the hives – both the test and control –were fed and inspected on the same schedule. All had their bottom board inserts removed, and then replaced, at the same time. All hives were worked using untreated, dried lavender stems in the smoker.

Our friend Dirt

We knew that some people who were trying Strats in their hives poured the media onto a piece of paper resting on the tops of the frames. We didn’t do that. We wanted the bees and Strats to interact directly as soon as possible. So after a routine inspection, we would pour premeasured Strat medium directly onto the frames of the top super of the brood nest. We scientifically named this procedure “dirting,” as in, “Did you dirt that one?” What it lacks in poetry it makes up for in accuracy.

The bees started clearing the media off the tops of the frames as soon as we started shaking it out. In one of the hives, we watched a bee drag her front leg the length of a frame, sweeping off a streak of dirt onto the bees below. The bees cleaned up our experiment quickly. The media was usually gone by the next visit.

By mid-August, C4 and C8 of the control hives and C14 and C15 of the Strat hives were not flourishing and we removed them from the test. (They were later combined with other hives or turned into nucs.)

Within a week or so of each Strat application, Varroa parts started showing up on sticky boards. Sorry, no pictures of either the Varroa bits or us jumping up and down in glee.

But good news in Summer meant nothing in Fall.

And then we got sad

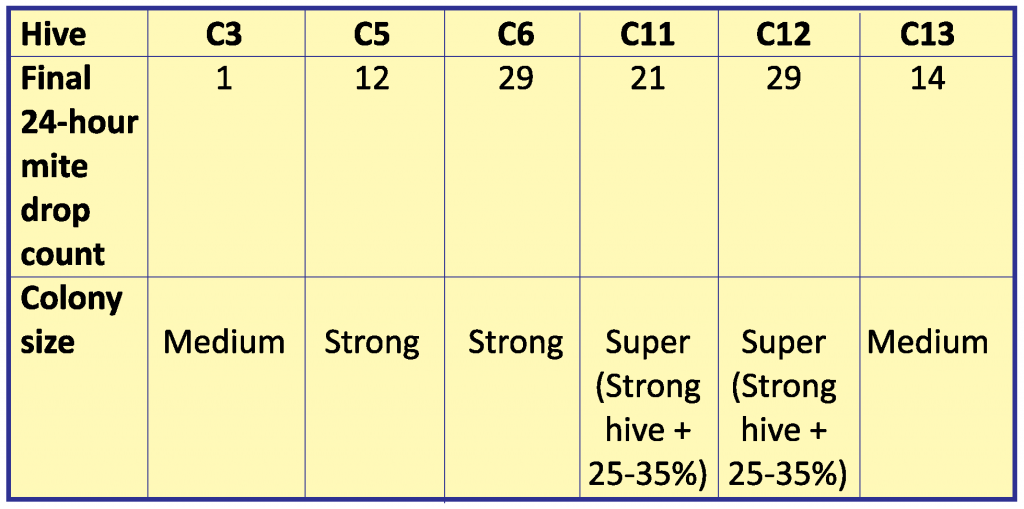

In September, we applied MAQS on all the hives in our C yard, including our control hives C3, C5, and C6 and our hives getting Strats, C11, C12, and C13. And we waited to see what we’d find on the sticky boards.

It was disheartening to see so many Varroa, with some sticky boards having more than 500 mites.

We were not the only beekeepers to see an alarming population explosion splattering the sticky boards after treatment. The president of our local bee club reported the same thing – hundreds of mites during mite fall days after treatment. Ultimately, for us, the mite fall for the control hives and the Strat hives was essentially the same.

A twist

Here’s the thing, though.

Strat hives C11 and C12 ended the season as the largest colonies in our apiary, by far. These hives were so big that we would rock-paper-scissors to see which one of us had to go through them.

There could be many reasons for this – the queens were particularly good, the location of the hives was just different enough, these hives benefited from drift, and so on.

We can’t say C11 and C12 had lower mite counts because of the Strats. Our sample size is small. We started with packages and packages are weird. Or perhaps what we were seeing was similar to using powdered sugar to dust bees.

Powdered sugar dusting appears to be weakly effective against Varroa. While at first enthusiastic about powdered sugar dusting, Randy Oliver reported in January 2015 less-than-spectacular results and also noted Dr. Amanda Ellis’s 2009 study, which showed only a slight reduction in mite levels with sugar dusting. A Honey Bee Health Coalition report (2016) states that sugar dusting was less than 10 percent effective.

The idea behind powdered sugar dusting is twofold. First, fine dust impedes a Varroa mite’s ability to hold on to the host bee, so it falls to its death (Ramirez and Malavasi 1991). Second, when bees get dusty, they start to groom, knocking off the Varroa (Macedo et al. 2002). And while powdered sugar may not be as effective as we’d all like it to be, perhaps dusting with a safe but irritating material (such as peat moss or lime like in the Strat media), combined with the Strats, might be.

At the time, it didn’t occur to us that maybe we should have applied media without Strats to some hives as part of our test. I can imagine an insect smaller than a Varroa mite tickling the hairs on a bee’s body as it makes its way through a hive, spurring the bees to groom more and knock off Varroa in the process. But that’s just a WAG (a spectacular term that means “wild-assed guess”), which is worth exactly what you pay for it.

There’s always next year

This experience gave some credence to our suspicions: as useful as Strats are, they’re not going to do much for honey bees. But neither of us is completely convinced. So here’s the plan: come Spring, we’ll again assess these hives’ strength, do an early mite count, and treat with Api Life Var if necessary. Then perhaps in May we will again start testing the Strats. This time, though, our control group will get only the media – basically, all dirt and no Strats. We’ll continue monitoring using sticky boards and alcohol wash throughout the season.

It could all end in tears and recriminations or with rainbows and unicorns. Whatever happens, it will be even more interesting than beekeeping already is.

References

Chandler, D., K.D. Sunderland, B.V. Ball, and G. Davidson 2010. Prospective biological control agents of Varroa destructor n. sp., an important pest of the European honeybee, Apis mellifera. Biocontrol Science and Technology 11 (4): 429–448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09583150120067472.

Ellis, Amanda M., Gerry W. Hayes, and James D. Ellis 2009. The efficacy of dusting honey bee colonies with powdered sugar to reduce Varroa mite populations. Journal of Apicultural Research 48 (1): 72–76. http://www.ibrabee.org.uk/component/k2/item/516.doi10.3896/IBRA1.48.1.14.

Honey Bee Health Coalition 2016. Tools for Varroa management: A guide to effective Varroa sampling & control. http://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/HBHC-Guide_Varroa_Interactive_18FEB2016.pdf.

Macedo, Paula A., J. Wu, and Marion D. Ellis 2002. Using inert dusts to detect and assess Varroa infestations in honey bee colonies. Journal of Apicultural Research 41: 3–7.

Mikheyev, Alexander S., Mandy M.Y. Tin, Jatin Arora, and Thomas D. Seeley 2015. Museum samples reveal rapid evolution by wild honey bees exposed to a novel parasite. Nature Communications 6, Article number: 7991. http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms8991#abstract.doi:10.1038/ncomms8991. Oliver, Randy 2013. An improved, but not yet perfect, Varroa mite washer. http://scientificbeekeeping.com/an-improved-but-not-yet-perfect-Varroa-mite-washer/.

Oliver, Randy, 2015. IPM 5.5 fighting Varroa 5.5: biotechnical tactics II, “Update January 2015—we no longer use sugar dusting.” http://scientificbeekeeping.com/fighting-Varroa-biotechnical-tactics-ii/.

Ramirez, B. W. and G. J. Malavasi 1991. Conformation of the ambulacrum of Varroa jacobsoni oudemans (Mesostigmata: Varroidae): A grasping structure. International Journal of Acarology 17(3): 169–173.

Sagili, Ramesh 2014. Final research report to the National Honey Board: Evaluating potential of predatory mite (Stratiolaelaps scimitus) as a biological control agent for Varroa mites and testing Amitraz (Apivar) efficacy and mite resistance. https://www.honey.com/images/uploads/research-projects/Evaluating_potential_of_predatory_mite.pdf.