Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Do I Have a Future in Beekeeping?

Do I Have a Future in Beekeeping?

A fifty-year reflection

By: James E. Tew

Figure 1. Jim Tew 48 years ago and 30 pounds lighter. The bee world in this photo is now gone. This is just a snapshot of a moment.

Your present perception of beekeeping is only a snapshot in time

Beekeeping today is not beekeeping past or future beekeeping. Apiculture as we know it is simply our version of present-day beekeeping. It will change. It always has. I am a member of a rapidly aging generation of beekeepers, who kept bees before predaceous mites arrived. Killer Bees did not exist. Those days are gone, and the beekeepers who remember those days are passing.

A friend and peer recently suggested to me that, whenever possible, I should record some of my pre-varroa mite memories and experiences. After all, our current bee management goal is to remove the parasitic mite load from our honey bee population. Present-day beekeepers would like for our bee management procedures to return to pre-1984, a time without mites in our honey bee herd.

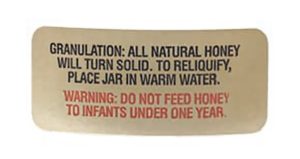

Figure 2. Infant Botulism warning label (Betterbee label, 2024)

I don’t mean to be a hero egotist

Much like a disaster appetizer, in 1978, researchers determined that Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (1) may sometimes be caused by botulism spores contained in honey. For the beekeeping industry, it was dreadful that pure, wholesome honey could be the occasional cause of an infant’s death. Unknown at the time, this revelation was a harbinger of more things to come.

Figure 3. A Varroa mite on a drone. The parasite that fundamentally changed beekeeping.

I don’t mean to suggest that I had major part in saving the Kingdom of Honey Bees, but the six-year period from 1984-1990, can only be described as beekeeping-ly hellish. I was there. In 1984, Tracheal mites were found in southern Texas. Beekeepers went crazy. Just three years later, in 1987, Varroa mites were found in the U.S. Beekeepers went even crazier. Canada and Mexico shut out U.S. bees. Six years after that singular event, in 1990, Africanized honey bees were finally found in southern Texas. This time it was the public that went crazy. It seemed that rabid honey bees were going to kill us all. It was a tough time to be in beekeeping. Honey was apparently poisonous to infants, predaceous mites were going to kill all our bees, and Killer Bees were going to kill many of us. This was a great time to recruit new beekeepers. Yeah, right!

We knew changes were coming

It’s not like beekeepers were asleep. All of the U.S. beekeeping industry had been alerted that these historic events were coming. The scientific and communication communities did a good job informing all beekeepers to prepare for the pending invasions. I wrote an article on this subject for Bee Culture magazine in 1985. Honestly, when writing this article forty years ago, I was trying to reassure myself as much as reassuring new beekeepers. The short article is reprinted below.

Figure 4. Barton Smith (Maryland) and Pat Powers (Virginia), left and center, working Venezuelan Africanized honey bees circa 1992.

Do I have a future in beekeeping? (May 1985)

A major part of my job is beekeeping education. In that capacity, I talk with a number of potential students as a matter of course. Such conversations were much easier a few years ago. There was no honey surplus(2) then. The hybridized bee (Killer Bees) were far, if ever, in coming, and few beekeepers had any idea of what tracheal mites were – much less varroa mites. Sometimes it seems that when it rains, it pours.

When a potential student asks me, “Do I have a future in beekeeping?”, what should my response be? I hear, as do all of you, the daily barrage of high interest rates, tight money and high incidences of agricultural default. Doesn’t sound good, does it?

When I was an apicultural graduate student at the University of Maryland, I stood in long lines with all the other “Organic Food Freaks” to get my wholesome organic peanut butter and bean sprout sandwich. I would have no part of salt or sugar in my diet. I only drank aseptic fruit juices produced without the benefit of any chemical pesticides whatsoever (at least that is what I was told and that was certainly what I wanted to believe). And everywhere, people wanted pure organic honey. Most local honey markets boomed, touting no in-hive pesticides and no adulteration.

Those long lines waiting to buy all those organic products seems now to have moved to my local grocery store. The thrust of organic food market appears to be centralized in the organic food stores or specified areas in local grocery stores. But it’s no longer the burning issue that it was.

So now with subsidized honey prices, Tracheal mites established here and more mites on the way, as well as killer bees, what do we do now? People, what should be done now? I really don’t know and I’m not sure who does know. But I can tell you some things that I do know about beekeeping.

Most importantly, I still enjoy keeping bees very much. I love the hum of an active hive on a warm Spring day – a day that, in my memory, is always bounded by blue skies and pleasant clouds. I’ll always enjoy the smell of foundation in a new pine frame, the aroma of a new crop of honey, the excitement of a big swarm, the satisfaction of producing nice, fat queen bees. Those things I am sure of.

In some regards, things have changed and are changing in beekeeping. We often overlook the fact some of these changes may very well be for the better. The new world of computers is presently a vast untapped resource. Soon, they will help us manage our hives more efficiently, keep our financial records more accurately and keep us better informed.

Figure 5. People and society have changed. It would be impossible to sell this extractor today with the drive mechanism so exposed. These two young men are preparing to spin cappings in cappings baskets.

Look at the improvement in extracting equipment. Not many years ago, there were belts and pulleys with levers everywhere. Now extractors have small compact motors controlled by electronic circuitry. It’s safer and more efficient. On the near horizon is the developing concept of recombinant DNA. With all its potential problems, it offers tremendous promise. Possibly some of our old problems such as developing disease resistant bees or controlling bee temper may be resolved. Researchers are understanding the biology of viruses more and more. Solving that problem could allow our bees to live longer thus making the hive more productive.

However, none of this changes the fact that tomorrow morning, several states will still have tracheal mite infestations. Nor will the great surplus of honey evaporate. It’s not hopeless though – not by a long shot. Beekeeping will survive. Admittedly, some aspects of the industry are going to change. And those changes may seem to be for the worst now.

Consider this. If the pressures our industry are now under results in a greater awareness of our industry by legislators, consumers and the public, then we have bettered ourselves despite the problem. If the tracheal mite arrival results in our industry being better prepared for the varroa mite, a far worse pest, then Acariosis(3) served at least one positive purpose. For the long run, things may not be as bad as they seem.

My effort here has not been to write a rah-rah article – to rally the troops, so to speak, but rather to address a difficult question that I’m frequently asked, “Do I have a future in beekeeping?” If one derives true enjoyment from beekeeping and understands the problems our industry faces, and if that person is aggressive, open-minded and creative, having the ability to take new ideas, techniques and technology and put them to work, then I can confidently and honestly say that from my experience, that person can have a promising career in beekeeping (Thank Heavens!).

In 1985, I was so naïve.

When I wrote that article in 1985, I was so naïve. All beekeepers of the time were unaware. Nothing could have prepared us for the wind-driven wildfire of the Varroa invasion of 1987. At the time, Varroa seemed to be killing every colony it invaded. Commercial beekeeping operations that were several generations old, were failing. People were dropping out of beekeeping on every turn. Why would anyone want to keep bees?

During sometime 1988, I attended an American Beekeeping Federation meeting somewhere in a western state. While I forget the exact date and the location, I do not forget the feeling I had at that meeting. During a Q&A session, concerning almost exclusively the new Varroa issue, a commercial beekeeper went the front of the session, and tearfully told the entire group of attendees goodbye. Predaceous mites had destroyed his business that he had inherited from his father and grandfather. No lending agency would front him money to stay in the bee business. At that moment, readers, I had the very real, somewhat selfish thought, “Do I have a future in beekeeping?” This was the same question that I posed in 1985, but this time, the question felt much more personal. That was the first time that I truly wondered if our bee ship was going down.

Figure 6. The effects of Varroa mites on a colony if not controlled in some way.

We had nothing with which to fight Varroa

Initially, beekeepers had nothing to use to combat the Varroa mite. After Varroa arrived, Tracheal mites had faded from concern. Tracheal mites were annoying while Varroa mites were usually fatal.

On October 20, 1987, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS) approved (Section 18, Crisis exemption) plywood strips soaked with Mavrik or Spur (fluvalinate) for detection of Varroa. On December 30, 1987, a section 18 special exemption approved plywood strips soaked with Mavrik or Spur as treatment. March 21, 1988 – Use of Mavrik was rescinded and was replaced by the miticide, Apistan(4).

Yes, it’s a fact. For a year or so, we beekeepers made our own mite control devices. Yes, before you ask, beekeepers everywhere were concerned about honey purity. The basic argument was that dead bees do not produce honey. Beekeepers were relieved to have Apistan become the grandparent of beehive chemical controls.

Interestingly, up until Varroa’s arrival, beekeepers universally disliked pesticides. Since the end of World War II, pesticides had been killing our bees. But in 1988, our industry desperately turned to pesticide companies to make products that would help control mites. At this very moment, we still depend on some of those companies to make products to help with honey bees’ predaceous mite problem.

The body count

I am reminded of some of the lines from the Ballad of Sir Andrew Barton:

Fight on, my men,

I am hurt, but I am not slain;

I’ll lay me down and bleed a while,

And then I’ll rise and fight again.

During those years, beekeeper numbers declined. Bee colony numbers declined. Meeting participation dropped. It was difficult to secure officers for bee groups. Winter kill rates for colonies increased. Indeed, beekeeping didn’t die, but it surely was bleeding.

Then Apiculture rose to fight again

Well, not quite that dramatically, but the shock of all we had been through began to wane. Beekeeping did begin to recover. Yes, we lost a lot of people. At the time, my two brothers and my dad were beekeepers, too. Dad grew too old for the work and my two brothers burned out. They quit.

But a somewhat unexpected effect of the Varroa invasion made itself felt. Many of the wild honey bees were eliminated. Commonly, growers did not feel the need for supplemental pollination. “Let the wild bees do it.” Apparently, in some areas, there were few remaining wild honey bee nests. The absence of pollinators was noticed. Supplemental pollination programs grew in importance and interest. The Africanzied honey bee issue began to decline. Pollination fees increased. Honey prices rose. Interest in honey bees began to rebound. Then Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) struck, but that is yet another story. If anything, CCD only increased the concern about the honey bee population decline.

Beekeeping today

In 1985, I wrote, “My effort here has not been to write a rah-rah article – to rally the troops.” That is still true in this article. Do you have a future in beekeeping? I have no idea. When it mattered most to me, I didn’t even know if I had one.

I do know this. Beekeeping came roaring back from its dark days, in a fashion that I never imagined. Women have become major participants in the bee industry. As I predicted, computers and electronic support grew in ways I did not have the ability to predict. The web. Smartphones. Educational videos. Bluetooth devices. Quality publications, like this magazine, evolved. Beautiful bee supply catalogs have become common. Remote streaming sessions on bee management abound. Higher honey prices and support for supplemental pollination are available to beekeepers. Who could have foreseen this present state of apiculture in the dark days of 1990?

And I also know this. Varroa mites are still right here, in my colonies, killing my bees. I will have higher Winter kill due to viral diseases vectored by mites. My queens once lived three to five years. Now, I get one season out of them, and they are much more expensive. Herbicides seem to be eliminating my bees’ floral sources. Time are much better, but we still have challenges.

But you should know this. Presently, beekeeping is absolutely beautiful when compared to what it was from 1984-1990. One of my stranger comments is that, with a few improvements, beekeeping today is better, more vibrant, more diversified and more inclusive than it was when I began to keep bees in 1973. Even with our present problems, we are in a good place. Enjoy it. Cherish it. It was a hard fight to get here.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

tewbee2@gmail.com

Co-Host, Honey Bee Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com

(1) https://ufhealth.org/conditions-and-treatments/sudden-infant-death-syndrome

(2) 2The U.S. Government has supported the price of honey since 1950 by providing market price stability to honey producers to encourage them to maintain honey bee populations sufficient to pollinate important agricultural crops. When honey support prices moved above the average domestic price in the early 1980’s, domestic producers found it profitable to forfeit their honey to the Government while packers and industrial users imported lower priced honey for domestic use. Changes made in the program by the Food Security Act of 1985 reduced forfeitures of honey to the Government and made domestic honey competitive with imports. Consequently, imports declined from 138.2 million pounds in 1985 to 55.9 million in 1988. At the same time, Government take-over of forfeited honey declined from 98 million pounds in 1985 to 1.1-3.2 million pounds from 1989 through 1992. Expenditures and takeovers will decline even further in fiscal years 1994 and 1995 with amendments to the Appropriations Acts, which eliminated deficiency payments and loan forfeitures for 1994 and 1995 crop honey. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/40618/50791_aer708.pdf?v=9286.4

(3) The tracheal mite, also known as Acarapis woodi, is an invasive bee hive parasite. Discovered in 1919 on the Isle of Wight, the mites cause a disease called Carine disease or Acariosis, which is deadly to bees. Without treatment, it can bring down an entire colony.

(4) Dave W. https://www.beesource.com/threads/what-is-maverick.200499/