Although beekeeping and foraging might appear to have little in common, it turns out that a large number of native or naturalized pollinator plants are suitable for foraging. With over half of the profiled species offering nectar, pollen, or honeydew, this is definitely a helpful guide.

Although beekeeping and foraging might appear to have little in common, it turns out that a large number of native or naturalized pollinator plants are suitable for foraging. With over half of the profiled species offering nectar, pollen, or honeydew, this is definitely a helpful guide.

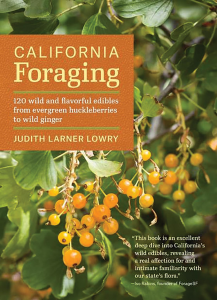

Of the various titles in this series that I’ll be reviewing, this one is my favorite. The user-friendly table of contents lists the plants alphabetically by common name. There is also a comprehensive index of common and Latin names. I like the fact that this stresses critical safety and sustainability issues as well as plant ID tips under each plant entry and in the introduction.

The author urges readers to be 100% certain of a plant’s identity before consuming it. Each plant entry informs the reader about the various habitats and regions of the state where the species can be found. Whenever appropriate, she provides information on similar species that are toxic or harmful.

Each title in the series features a quick, handy, seasonal guide to foraging. However, I found the format of this title’s guide to be the most convenient and accessible of the volumes. Presented in an easy-to-use chart with the species listed alphabetically by common name, this has columns for each plant part and harvest time.

Each color illustrated plant profile gives the common and Latin name, a brief introduction, details on plant identification, when, how, and where to harvest, sustainable harvesting tips, and culinary ideas. The appendix features a list of websites and references. In addition, the author promotes the use of native species in landscapes.

While some of the plants presented in this volume are unique to California, others do occur in other regions of the country or have relatives that can be found elsewhere. The book features over 25 or so related species that I’ve profiled in Bee Culture articles over the years.

Let’s look briefly at some edible honey plants that appear in this guide. These are chaparral yucca, fennel, salal, and tarweed. Some honey plants that also bring pollen are the nightshades, the walnuts, wild buckwheat, mountain pennyroyal, buttercups, California bay laurel, and assorted oaks.

Other nectar and pollen sources featured in this title are yerba santa, miner’s lettuce, farewell-to-Spring, poached egg flower, mule’s ear, chickweed, wood sorrel, tree mallow, and red maids. Nectar and pollen plants that can sometimes bring honey are elderberry, radish, mallow, plantains, and tree hollyhock.

Some of the plants profiled by the author that are sources of honeydew are the filberts and hazelnuts (also sources of pollen), the various walnuts, oaks, pines, and Douglas fir. Species that offer pollen are docks and some grasses.

Certain species in this book are quite praiseworthy nectar and pollen plants that deserve much more recognition than a mere mention. For that reason, I’ve selected a few of those to discuss below in greater detail.

Blue Palo Verde

(Cercidium or Parkinsonia florida)

A member of the bean family, this species occurs in California, Arizona, and Nevada. Suited to zones eight through eleven, the plant is most common from 1200 feet elevation to sea level in desert grasslands, canyons, desert scrublands, and hillsides.

Adapted to most all well drained soil types and pH levels, this salt and drought tolerant native prefers full sun. Blue palo verde experiences minimal disease and pest problems.

The fast growing, deep rooted species with a bushy spreading crown is typically 15 to 20 feet tall and 20 to 25 feet across. A spectacular shade tree for landscapes, it features stout, spiny, crooked branches and green, zigzag, thorny stems. The trunk is usually less than a foot in diameter.

The deciduous, doubly compound, greenish-blue, alternate leaves are about an inch in length. Typically short-lived, these can contain numerous pairs of very petite leaflets.

One of the common names –shower of gold – refers to the vivid yellow flowers. From March to May, masses of the large, scented, showy blossoms conceal the branches. Less than an inch across, the flowers contain five petals with the largest one sometimes displaying a reddish blotch. Blossoms appear on 4½-inch-long clusters. The flat seed pods grow to 3¼ inches in length.

Related Species

There are several related species that occur mostly in the Southwest. Small leaved or little leaf palo verde (Parkinsonia microphylla) is native to California and Arizona. Other common names are foothills palo verde and yellow palo verde. This inhabits desert plains and the foothills.

A spiny shrub or small tree with greenish-yellow bark, the long lived plant pretty much resembles blue palo verde. Reaching 20 feet or so in height, it differs by having slightly lighter colored blossoms with a mix of pastel yellow and white petals. These appear on one-inch-long clusters. The foliage consists of numerous pairs of hairy leaflets.

Texas palo verde (Parkinsonia texana) is restricted to Texas. Up to 25 feet in height, this tree features green bark. Several varieties of the plant occur across the state.

Bee Value of the Palo Verdes

Providing nectar and pollen, these are reliable sources of honey in parts of the Southwest, especially spots at lower elevations that are higher in soil moisture. Typically yielding about 30 pounds of honey per colony, this can sometimes provide much larger honey surpluses.

Ranging in color from clear to light yellow or light amber, this heavy bodied honey has a pleasant yet characteristic flavor. It compares very favorably with alfalfa honey in terms of quality.

Manzanita and Bearberry

(Arctostaphylos spp.)

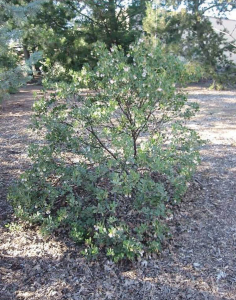

Members of the heath family, these are most common in the western states. About 50 species are native to North America. The overall size and growth habit can vary slightly by species. The group includes both tall, upright types as well as low growing ones. Some of the latter are only one to two feet or so in height and are often grown as ground covers. The larger ones can reach 20 feet in height.

Typically, these exhibit picturesque, crooked branches, and lovely purple or red bark. The attractive, evergreen, oval, leathery, green leaves are usually one to three inches long.

Forming nodding clusters, the solitary, waxy, bell-like to urn-like flowers are likely familiar to beekeepers. Resembling the blooms of other heath family relatives, such as the blueberry, they’re mostly white or pink. The flowering time can vary by species. With favorable weather conditions, these can typically bloom from Winter to Spring. In California, flowers are present mostly from November to February.

The fleshy fruits are long lasting drupes. The color can vary by species, but are often red or brown. Ripening in Summer to Fall, they can be quite showy in some cases. Around ½ to an inch in diameter, these contain one to ten stony seeds according to the species.

Growing Manzanitas and Bearberries

Depending on the species, these are suitable for shade to full sun. The plants demand well drained conditions. The pH preference varies slightly by species as well.

Moderate watering is needed until they become well established. Overwatering and wet soils can lead to stem and root rot. Propagated by cuttings, these experience few pest problems other than aphids.

Bee Value of Manzanitas and Bearberries

All of these species are major bee plants in the Southwest, the West, and the mountain states. Yielding both nectar and pollen, the blossoms are quite popular with bees. These flowers help build up colonies.

Some species are reliable sources of nectar in certain areas of California. The nectar flow is best with warm days and cool nights. The frost-proof blooms secrete so much nectar that it can be shaken from the stems.

In some locations, large crops of honey are possible – up to two full supers. However, the average is generally around 40 pounds or so per colony.

The excellent flavored, heavy bodied honey has an aroma much like that of the flowers. Light amber to white, the honey from the various species tends to be fairly similar.

Other Recommended Bearberries and Manzanitas for Bees

Some of the related species that are known to be especially good honey plants include the following. Suitable for zones three through eight, bearberry or kinnikinick (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) is by far the most widespread species of all. It occurs in all states except Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and along the Gulf from Texas to Florida northward to North Carolina. The species favors ridges, sand barriers, and dunes.

This shade tolerant, mat-forming, acid loving plant is often grown as a ground cover. The trailing stems root wherever they touch the ground. Typically less than ¾ foot tall, bearberry can be quite wide – four feet or so.

The leathery, shiny foliage is green. The pale pink to white blossoms appear in Spring. Berries are pink to red.

Reaching 10 feet or so in height with an eight foot spread, bigberried manzanita (Arctostaphylos glauca) is hardy to zone nine. Native to California in chaparral, this can begin flowering as early as December, depending on location. The spreading shrub features lovely brownish-red bark.

The gray-green foliage is three inches long. Emerging in large clusters, the pale pink to white blooms feature downy flower stalks. The large fruits are orange to red.

The common manzanita (Arctostaphylos manzanita) reaches two to 20 feet in height with a six to ten foot spread. It is hardy to zone eight. Common in California, this small tree to tree-like shrub with crooked branches features reddish-green bark and dark green, oval foliage, up to 1½ inch long. The white to pink blossoms emerge over a 1½ to two month period. Initially white, the berries later become red.

Dwarf or glossy leaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos nummularia) is an acid-loving species that blooms during mid-Summer. Typically ½ to five feet tall and twice as wide, this occurs in California in northern coastal areas. Hardy to zone seven, it bears pink or white blossoms in Spring.

Greenleaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos patula) is hardy in zones five through eight. Preferring full sun, this native is found on dry slopes, glades, and open woods in Washington, Oregon, Montana, California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. The plant is typically three to six feet tall and equally wide.

The picturesque shrub is noted for its twisted, gnarled trunk and multi-hued, peeling bark. The thick, stiff foliage is medium green to greenish-gray. The white to medium pink blossoms open in Spring.

Hairy or Columbian manzanita (Arctostaphylos columbiana) is hardy in zones eight and nine. Native to Washington, Oregon, and California, this reddish barked, hairy twigged shrub or small tree with a fast growth rate reaches five to seven feet in height and is almost as wide. Hairy when young. the greenish-gray foliage is three inches long.

The plant bears white flowers during the Spring. Although the honey can initially taste somewhat bitter, this diminishes with time. The berries are scarlet.

Pine mat manzanita (Arctostaphylos nevadensis) is a sun loving, Spring blooming species. It is reliably hardy in zones seven through eight and marginally hardy in zone six. Only ¾ to two feet in height and a spread of up to three feet, the plant occurs from Washington and Oregon to California and Nevada in open woodlands and outcrops.

Variable in growth habit, this very dense species features many crowded, twisted, brightly colored stems. Pine mat manzanita bears pastel pink to white flowers in Spring.

Sticky whiteleaf manzanita or silver manzanita (Arctostaphylos viscidia) is native to California and Oregon. Hardy to zone six, this shrub or tree reaches eight to 20 feet in height. The pink and white flowers are followed by red fruits.

Woollyleaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos tomentosa) is the second most common species in California. Hardy to zones eight through 10, it is named for the downy covering on the new stems and the newly emerged leaves. The plant can grow to eight feet in height.

Connie Krochmal is a beekeeper, writer and plant expert living in Black Mountain, North Carolina. She is recommending California Foraging-120 Wild and Flavorful Edibles from Evergreen Huckleberries to Wild Ginger by Judith Larner Lowry, 344 pages, Timber Press, to beekeepers.