By: Ann Chilcott

This is the first article in a three-part series on bee farming in the United Kingdom by Tony Harris N.D.B. (National Diploma in Beekeeping), and Ann Chilcott B.A. (Bachelor of Arts degree). Both authors hold Scottish Expert Beemaster certificates and are freelance tutors and writers living on the Scottish Moray Coast, and in Highland Region respectively. Tony is also a bee farmer and will, in the subsequent articles, discuss from personal experiences the current challenges of bee farming in 21st century UK. I am a hobby beekeeper who has kept bees and produced honey for sale in my village for 14 years.

To understand bee farming in the United Kingdom (UK), it is essential to know how geography and climate influence and limit the success of beekeeping in this country. You may be forgiven for thinking that the UK is a small island with much the same climate and conditions all over. However, it actually comprises many islands; the country of Scotland alone boasts 6,160 miles of coastline and 790 islands of which many are inhabited. Also, the climate varies markedly from north to south and east to west.

The population of the UK is around 67 million spread over England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. Scotland, where we live, has a population of around five million and is in the northern third of the country separated from England by a 60- mile border. Scotland is about the same size as Colorado or Wisconsin. Our indented northern and western coastlines are swept by the Atlantic Ocean whilst the east coast is lashed by the North Sea, and the south coast by the Irish Sea.

The oceanic climate of the UK is temperate and very changeable and the west coast is greatly influenced by the gulf stream carried by the Atlantic Ocean, so much so that tropical palm trees flourish on Scotland’s west coast. However, the east coast is cooler and dryer and more likely to have heavy snowfalls in Winter. At higher altitude, in places like Braemar in Aberdeenshire, it is not unusual to experience very cold temperatures, sometimes down to -27°C (-17°F), and 59 days of snow annually compared to less than 10 days in the south and west.

The rainfall in UK is heavier in the west than in the east. For example, on Scotland’s west coast the rainfall can exceed 120 inches/3,000 mm annually in some places while in the south of Scotland it can be less than 31 inches/800mm. The UK has milder Winters and cooler and wetter Summers than residents of areas on similar latitudes such as Labrador and the Moscow region, but Scotland experiences lower temperatures generally than the rest of the UK which limits forage crops available to honey bees.

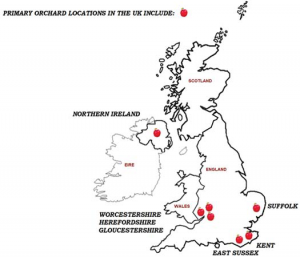

In this climatic context it is easy to understand why honey yields are generally higher in the south of England than in the north and why Scottish bee farmers seeking pollination contracts must mostly head south of the border to the top fruit orchards of Kent, East Suffolk, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire. The total area of UK orchards is 17,500 hectares/43,000 acres growing apples, plums, pears, apricots, cherries and even figs as the climate warms. The area of apple orchards is 14,468 hectares/35,750 acres which is approximately the size of the cities of Liverpool in England or Scotland’s Aberdeen which are 71 square miles. I believe that this would be about the same size as New York State’s city of Rochester, the home of Kodak.

The fertile region of Tayside around Dundee in north east Scotland is an exception having more sunshine, and rainfall on a par with parts of England so this area is renowned for soft fruit growing and the poly tunnelled fields in the carse of Gowrie bear testimony to the success of fruit farming here. Back in colonial times and the heyday of industry, Dundee was famous for jute, jam and journalism. Now the jute mills are silent but the buildings rejuvenated and filled up with restaurants and offices in a city regeneration scheme. Jam and journalism still flourish.

How did we progress to farming bees and honey production in the UK? Well, it is a relatively new agrarian activity compared with bee farming in the U.S. where you folks are ahead of us by around a hundred years. It required a brave beekeeper to make the move from hobbyist to bee farmer and Robert Orlando Beater Manley (1888-1978) was our man. Known to his friends as Bert, and, under his pen name R.O.B Manley, he wrote widely and invented things like the Manley system of frames, adding thymol to prevent mould in sugar syrup, and actually feeding bees sugar over Winter. Manley was the first man in 1948 to manage 1,000 colonies in England though a Mr Gale was another early commercial beekeeper managing many hives around that time.

Manley, a pragmatist, was highly regarded as an authority on bee farming and today his advice still remains relevant. He regarded the hive as the most important tool in the business and at that time in the UK the double-walled, 10-framed WBC hive (designed by, and named after, William Broughton Carr) was the most popular design. These hives are charming but unwieldy.

The hive types used in UK and Ireland then reflected the hobbyist element to beekeeping however, and Manley looked further afield to the U.S. for the perfect hive. He wanted one with a flat, rather than gabled, roof and no legs or projections to make stacking and transport manageable. Obviously, the hive needed to be sturdy and made of sound timber to keep out the rain, so he advocated the use of the Langstroth, Modified Dadant and British Standard hives to provide more space and meet his needs.

Manley1 was way ahead of his time in dismissing “the fads and unnecessary trimmings that so delight the hearts of those who want to “keep Bees.”” Just take a look at the latest tantalising beekeeping supplies catalogue on either side of the Atlantic today and ask yourself, “do I really need that?” when your eyes rest upon the latest “must have” fancy gizmo and gadget.

Manley’s famous quote,2 “There is a lot of difference between keeping bees and being kept by my bees” resonates soundly today with bee farmers, and Manley recognised, that hobbyists in his time looked for any excuse to disturb the bees, “it is called “Manipulating” them he says3. “The poor creatures are to be commenced upon in March and ceaselessly tormented until Winter brings them respite.”

His dry sense of humor makes reading his books enjoyable today and I think that you may be amused to know that he didn’t like the taste of honey and, according to anecdotal rumor, he coped with honey drips whilst bottling by using his wife’s vacuum cleaner when she was out shopping.

Manley worked hard to change the focus on beekeeping away from being purely an amusing hobby to being a professional way of working with bees to produce a marketable commodity. The climate and weather were as challenging then as they are now but Manley ended his 20-year bee farming career wishing that he had started 20 years earlier.

UK Farming has changed markedly since Manley’s day with a reduction in clover pastures, wild flower meadows and hedgerows; these have been replaced by large areas of mono-culture crops such as oil seed rape, borage, and field beans. In Scotland, a lot of barley is grown for the whiskey industry so the main mono-floral forage crops for honey bees here are oil seed rape and, if the weather permits, ling heather towards the end of Summer.

Today, our bee farmers are represented by the Bee Farmers’ Association (BFA) with a membership of around 470 members managing some 60,000 hives between them amounting to 35-40% of the UK’s total hives. Around 30 of these are Scottish farmers. Interestingly, the UK classification of bee farming differs from that of the US based on hive numbers. Bee farming on a large scale in the US is defined by having around 3,000 colonies, whilst in the UK running 150 or more colonies, defines large scale beekeeping.

The criteria for BFA membership are no longer figure-based. Eligibility depends upon demonstrating that beekeeping is practiced for profit from which income is mainly or partly derived. The applicant needs to be developing or operating a bee farming business, or is employed on, or working on, behalf of a beekeeping related business or organisation.

You can see how the direction of bee farming in the UK has been shaped by climate and geography and how it is a relatively young endeavour. We expect that bee farming will change further in the near future. The demand for honey has risen and the bee farmers produce only around 15% of the honey consumed here compared with 60% on average for other European countries, so there is much potential for expansion in bee farming. On the other hand, there has been a decline in the number of bee farmers over the last 20 years and a rise in the average age of beekeepers; half the BFA membership is over 65 years. Consequently, the industry is seriously challenged today. In the following articles, Tony Harris will address some of these issues.

References:

1,2,3Manley, R.O.B. 1948. Honey Farming. Faber And Faber LTD, London.