Got A Question? He Knows!

by Phil Craft

A beekeeper in Kentucky writes:

Ordered my bees for April 2016. I plan on setting up four hives. I have made all my frames and boxes from scratch and am wondering if I can add 3# package bees into all foundationless frames?

I have added a 1” starter strip of foundation to all of my frames, but, I’m not sure if I should add full sheets of foundation in lieu of the 1” strips or if I should alternate full sheets and 1” strips. I’ve read that it will create too much “Bee Space” and that I should use full sheet of foundations. I do not have any drawn out frames, as I’m new to this.

I plan on retiring next year and my plan is to raise bees.

Any insight will be helpful.

Phil replies:

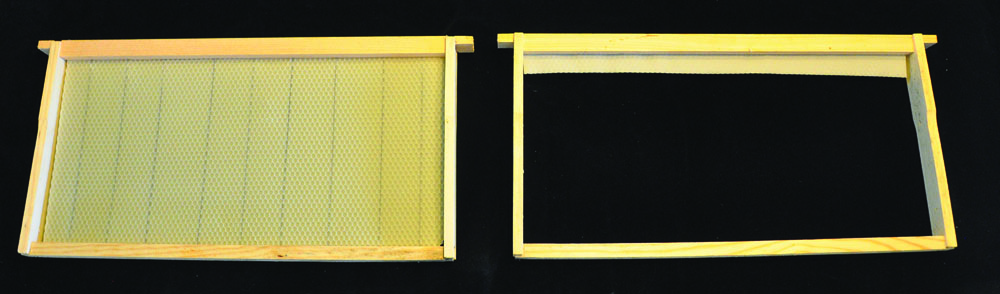

The development of wax foundation was one of many innovations that came about in the late 19th century during what I refer to as the beekeeping renaissance, ushered in by the widespread use of moveable frames in something resembling our modern bee hive. Other equipment advances included the smoker and the extractor. The advantage of foundation is that it gives bees a template from which to draw out beeswax comb. Without it, they would still form combs of perfect, hexagonal cells, but might attach them to any surface in the box and extend them in any direction. When placed properly, foundation results almost 100% of the time in combs drawn out within frames, allowing easy frame removal for inspections or for honey extraction.

In spite of such desirable results, some beekeepers over the years choose alternative methods. My paternal grandfather kept bees in the first half of the 20th century. He passed away in 1948, before I was born, but according to my uncle who helped tend his hives, Grampa never used full sheets of wax foundation. Instead, his new frames began with starter strips such as you describe. About 15 years ago while visiting with an aged beekeeper in the mountains of my native Eastern Kentucky, I watched him installing strips about an inch wide, cut from whole sheets of wireless foundation, in the tops of his frames. I told him about my grandfather and surmised that this must be an old-time mountain beekeeping tradition. “No”, he replied, “This is poor man’s beekeeping. Whole sheets cost too much.”

These days, those who decide not to use wax foundation are more likely to be concerned about contaminants than cost. Beeswax tends to absorb chemicals, and some studies have shown low levels of synthetic miticides in commercial wax foundation. For my part, though I understand the concern, I don’t think the amounts detected warrant abandoning such a useful tool. However, others disagree. Ask ten beekeepers the best way to approach a problem and you will get eleven different answers. Wax foundation, no foundation, plastic foundation, starter strips – as my friend Kent says, “The bees don’t care”, but what works for them may not work best for the beekeeper.

I experienced that first hand a few years ago when I decided to add a couple of supers for cut comb honey on one of my hives. I thought it might be a good opportunity to try starter strips. Typically, any type of comb honey is started on special, extra-thin foundation in order to incorporate as little foundation wax as possible in the finished product. My thinking was that if I used starter strips and then cut the comb honey from the area of the frame below the bottom of the strip, my cut comb honey would consist entirely of pure, foundationless comb. The problem was that the bees did not choose to cooperate. While they generally built wax between the boundaries of each frame, their execution was far from 100%. Sometimes they decided to connect two adjacent combs; occasionally they ignored my starter strip altogether. I had to perform what I call corrections. Almost daily for a week or so, I pulled up every frame from each box and removed any comb drawn outside the frame. In the end, I did have beautiful frames of comb honey – without foundation, but not without regular, painstaking intervention on my part at the beginning of the process. After cutting the comb honey from the frames and allowing the bees to rob the remaining honey from the strip at the top (as I always do with wet, extracted comb), I stored the frames. The next year I placed them, with the strips of drawn comb, on a strong hive, and was rewarded with two more boxes of beautiful comb honey. That time, less correction was required. For me, with only two supers to manage, this was workable. If I were trying to produce 50 supers of comb honey, I might have to rethink my method.

I am concerned that, as a beginner with four hives, you are creating an additional challenge for yourself. Four hives means four boxes with a total of 40 frames to begin with, and another 40 when you add your second deeps. If you do not check each of them, on an almost daily basis for several weeks, you could easily end up with frames that you cannot remove individually to examine. In just a few days, the bees could create a real mess that you, as a new beekeeper, might not be prepared to handle. We use foundation because it simplifies one part of a complicated process – good for the beekeeper because it’s less work, and good for the bees because it allows us to take better care of them. Alternating frames of foundation and frames with starter strips is unlikely to help, and might make things worse. As you say, the large space between the full sheets is an obvious violation of the bee space.

I am often concerned that those of us who encourage and welcome new beekeepers into the craft tend to emphasize its very real rewards and downplay the difficulties. It is not easy. In the beginning there is a steep learning curve. There are so many things to learn that beginners can quickly feel overwhelmed. When my kids started to drive, we let them learn on an automatic, though my wife and I drove (and still drive) cars with standard transmissions. My son even borrowed my brother’s automatic to take his driving test. Not having to shift gears gave them one less skill to master in the beginning. After they got their licenses, we taught them to use a clutch. I think it worked out better.

Starting with four hives is ambitious enough without adding complications. My suggestion is to use frames with full sheets of foundation and get through your first year. With a little experience and with the free time you will have after you retire, you may decide to expand. That would be the time to shift gears and experiment with starter strips or any other ideas you may have read about and considered trying. Good luck to you!

A beekeeper in Tennessee writes:

I lost about 30 frames of honey to SHB this past year (2015). I think this occurred because of queen problems. I kept cutting queen cells out. It was my 2nd year as a beekeeper. I hope I learned my lesson. This year I’m going to let the bees work it out.

Phil replies:

In spite of all the books, magazines, classes, and online information available to beekeepers these days, experience is still sometimes the most effective teacher. Congratulations! You just graduated from Beekeeping 205 – how not to attempt swarm prevention.

As I discussed in my column of January 2016, small hive beetle damage virtually always occurs as a secondary issue. The primary cause is an event which reduces the number of healthy bees in a colony, allowing small hive beetles to reproduce in large numbers uncontrolled by the hive’s legitimate population. While Varroa mites continue to be our greatest challenge, often creating an opening for small hive beetles to exploit, the loss of a queen is also a common precursor to beetle damage. All too often this loss is brought on by a beekeeper attempting swarm control by removing or “cutting out” queen cells.

When a colony prepares to swarm, it produces dozens of queen cells – a wasteful but usually successful strategy for assuring a viable replacement for the old queen after she accompanies the swarm from the hive. It seems logical then, that depriving the colony of the means of making a new queen will prevent it from swarming. Usually, however, it merely delays the process. In fact, bees themselves sometimes destroy queen cells to temporarily interrupt swarming when, for instance, inclement weather prevents their flying at about the time that the cells are ready to be capped. They soon resume swarm cell production, just as they do after queen cells are removed by a beekeeper. As Hamlet told Horatio (confusingly and in a completely different context), “If it be now, ‘tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come – the readiness is all.” In other words, some things are going to happen no matter what we do. Swarm cutting is only effective if done thoroughly and repeated weekly until the conditions driving the swarming urge (such as overcrowding combined with a strong nectar flow) have passed. If the beekeeper misses just one or two cells hidden in a clump of burr comb, the swarm will still depart. As a swarm prevention strategy, cutting out queen cells is time consuming, labor intensive, and has a low rate of success.

However, the real problem occurs when a beekeeper removes all of the queen cells, not realizing that the swarm has already departed! The old queen is gone and so are the cells from one of which her successor should have emerged. The chances of the colony’s making a new queen are drastically reduced since the old one usually quits laying several days before leaving and, consequently, the hive may not contain any larvae young enough to be developed into a queen. Even if a successor is produced, it can only be after a delay of several weeks. That means that the natural loss of aging field bees will not be compensated for by emerging brood. The population of the colony will suffer at time during which it should be at its most productive. How is this possible? It seems as though it should be obvious when a swarm has taken place by the reduction in the number of bees, but that is not always the case. Many a time I’ve had a beekeeper tell me that he spotted a swarm in his apiary, but since all of the hives still seemed full of bees, he had no idea which one it had come from. I’ve had the same experience myself. Colonies have an amazing ability to build up rapidly under the right conditions and the number of bees in a hive is difficult to estimate, especially to the eye of an inexperienced beekeeper. Even cutting out swarm cells before they are capped does not guarantee that you are catching them pre-swarm. Though bees usually swarm just after sealing the queen cells, they have been known to take an early departure. Destroying queen cells always entails some risk of creating a queenless hive.

As a speaker, I sometimes give talks on swarm reduction. Note that I say reduction, not prevention. Inhibiting the natural urge to swarm, which is the method by which colonies reproduce, is a difficult task and one on which many beekeepers tend to place too much emphasis. I frequently have occasion to talk with the owners of commercial apiaries, and I never hear any of these highly skilled beekeepers express concerns about swarming, though of course it occurs in their bee yards too. However, commercial beekeepers make a lot of nucs – an effective way to reduce swarming (though that is an incidental benefit to them.) After all, swarming is just the method nature has evolved for making splits, and swarm colonies can be thought of as nature’s nucs. Whether natural or engineered by beekeepers, the creation of new colonies reduces congestion in the brood box, increases genetic diversity, and helps the species to grow and thrive. Making nucs is the method of swarm reduction that I recommend to beekeepers and the one I practice myself, along with trying to recapture the swarms which do occur and settle temporarily in the trees in my apiary. If you don’t want to manage additional hives, nucs can be sold, used to bank extra queens, or saved to combine with a weak colony later in the season. Or you could just let the swarms go. Healthy colonies are capable of producing a good honey crop even after swarming. As you put it, let the bees work it out.

If you would like to learn more about the swarming process and add to your beekeeping library, I recommend two books: Biology of the Honey Bee by Mark L. Winston, and Honeybee Democracy, by Thomas D. Seeley. If you want information on reducing swarming, I also suggest Swarm Essentials, by Stephen J. Repasky. And don’t forget to keep an eye on the trees!