By : James E. Tew

“I can hear you!”

Many years ago, I had what was to be a “typical surgical procedure.” It went seriously wrong, and it would appear that I had a (very) close call. No problem for me. I slept through the entire event. But…when I awoke, the pain and discomfort level immediately let me know that things were not right. From my darkened room in the intensive care wing, I could hear a low, muted conversation between my surgeon and my neighbor who is a gastroenterologist. My surgeon was saying, “Many unexpected things went wrong in his procedure that made the process complicated.” He continued the conversation by quietly saying, “This is one that I will never forget!” All the while, I was trying to say, “I can hear you! I can hear you!”

Like my surgical experience, this colony is one that “I will never forget.”

One memorable colony sent a mouse up my pantleg. I will never forget that colony. Another colony – while face-to-face with a four-year old, veil-protected, little girl, sent an angry bee up my right nostril. The kid was not impressed. I will never forget that colony. Yet another colony was literally lost for nearly thirty years, and when found, was alive and in good health. I will never forget that one either. Of all the thousands of colonies that have been a part of my bee life, I only truly remember a specific few. I recently added another bee colony to my life’s unforgettable bee colony list.

I didn’t see this colony memory coming

During the Spring of 2017, I had a beautiful swarm move into empty equipment that I had stacked in my apiary. I was there and savored the moment. Free bees! This swarm had probably left another beekeeper’s hive and had decided to move to my facility. All was good. I made photos. It was a powerful swarm and quickly developed into a juggernaut. It was feisty, but it was powerful. No surprises there. I made a split. All was successful. All was enjoyable – except bees from the colony seemed to be stinging a bit much. As the colony grew, the number of stings grew. At full strength, this beautiful colony had developed a very annoying stinging personality. It was hostile all the time. It seemed to be keeping the other colonies upset. Alternatively, maybe other colonies were keeping the big colony agitated. There were so many flying bees, it was difficult to tell.

Then it happened. Bees from the powerful, rogue colony attacked my neighbor as he mowed his lawn. (at least I thought it was the big, beautiful colony doing the deed) That was the limit. I had to do something. It had to go and go quickly. I considered destroying the colony, but I blinked. I was not totally sure that it was the villain hive.

I decided to move the suspect colony to a new location about an hour away. This was a frustrating, time consuming, pile of work. Honestly, I didn’t care if the colony died. (I know, I know – requeen, etc. I had many reasons for my decision not to requeen that I discussed in Bee Culture, June, 2017.1) Once it was relocated, life in my apiary returned to normal. I chose the right colony as the troublemaker. Out-of-sight, out-of-mind. I ignored the troublesome colony that sat alone 40 miles from me.

The bear attack

During June, 2018, (I wrote about this event in: Bee Culture, August, 2018.2) a bear totally destroyed my beautiful, abandoned, annoyingly, frustrating colony. This was a complete surprise to me and, no doubt, to the bee colony. There had been no bear sightings in this area in nearly 100 years. The hive equipment was scattered and robbed. A stench of dead, decaying matter, and feces pervaded the area. Yet another frustrating task compliments of this free-swarm colony.

Of course, it was raining. The area was disgusting and soggy wet – but this site was not my property, so I tried to clean up. As I neatened things up and restacked equipment, I thought to myself, “at least this colony is finally gone.” Honestly, I didn’t think it would even survive the 40-mile relocation, but it clearly had. But now it was bear-destroyed and finally out of its misery.

In the cool, rainy weather, as I restacked scattered equipment – without warning – I moved an upturned deep only to expose about one-two pounds of the maddest bees I have recently encountered. I was not wearing protective gear – why? The bees were most certainly dead – none needed. Well they were most certainly not dead and protective gear was quickly needed.

It was late June. All major flows were long over. I could kill this colony now or just let it die a (somewhat) natural death. Since, at the moment, I had no ready way to destroy it, I just left it to deal with its own fate. On June 27, 2018, I essentially abandoned the colony – again. Once more, Out-of-sight, out -of-mind.

Your bees are alive . . .

My good friend, Bob, a beekeeper himself and also the land owner, gave me a surprise phone call in mid- September, 2018, to tell me that the rogue, un-killable hive was still living. Good grief! What is it with this colony?? I had no idea the colony even had a queen, but I did know that the colony had very little – if any – food stores. They might very well be alive now, but this unit would become a winter kill statistic next spring. Even so, I opted to make the 80-mile round trip to put some stores on a colony that didn’t have a future. Truly, I had good intentions. Then, Thanksgiving, family visits, leaves falling, home chores, and home bees – you know the drill – out-of-sight, etc. They never got supplemental feed.

Some cold weather hit early – and it hit hard

Several cold spells came early and were significant. Temperatures dropped to the mid-teens at a time when my lawn still needed mowing. I would occasionally think of the colony, oh so far away, and accept the fact that this colony with such an annoying personality was finally dead. For the first time, I had a guilt pang. This was a continuingly, frustrating colony that had caused extraordinary amounts of work, effort, and pain – but, the colony had never quit trying to survive. I should have found time to go down there. Wow, guilt has a bitter taste. But alas, bees without stores could not survive this.

Your bees are (still) alive . . .

After all this saga . . . after all this colony had endured, on December 6, 2018, another phone call from Bob told me that colony was still alive. Okay, this is truly strange. The bee cluster simply had to be hanging onto the very edge of life. It simply had to be. I conjectured there could be no food stores. Except for a spotty fall flow, there was nothing. Nothing! I, too, then became alive. This bee cluster deserved a better beekeeper.

The absolute best I could do was make the trip two days later. I felt certain that the colony would die within those two days. Like a movie with a sad ending, this colony would go through all of this turmoil and then die just as the supply truck was enroute. Maybe for the first time, I worried for this stingy colony. Two days later, with a full deep super, Bob and I loaded up for the ride.

It was cold, rainy, and muddy at the site

Every time I have interacted with this beehive, it has been rainy, ugly and sometimes, painful. Why would I expect any difference?

It was cold, far below clustering temperature. Even so, having some clear, painful memories of being whimsical with this beehive and having been suitably admonished for that oversight, I gently removed the outer cover. I noted a good sign on the outer cover. here was a bare spot right in the lid’s center that was free of snow.

That meant that the colony had, at least, been alive within the past few days. I cautiously cracked the inner cover and exposed – what??

You know it was alive

You know it was alive or I would not have written this article. What you did not know is that the colony was not only alive, but alive and well. I kid you not. I kid you not. Counting this piece, I have three published articles about this colony – all its trials and tests – and it not only survived but looked good. In fact, not only did it look good, it looked very good. I have been fiddling with bees and their biology for forty-five years, and I predicted that this colony would be dead on multiple occasions. Other than to be left alone, this colony needed nothing from me.

The cluster was centered. There was honey in frames on all sides. The cluster was compact and clean. There were no indications of dysentery or dead bees on top bars. The landing board was clear. There were no dead bees near the hive front. I hefted the hive from the back and discovered the hive had good weight, not dead weight, but certainly heavy weight. Without breaking the cluster, this bee colony appeared to be perfect.

How in the bee world could this colony have recovered from nothing in June to this extent in December?

The mystery nectar/pollen flow . . .

I have said many times in several articles that I try to first select the simplest of the possible answers to a given problem or question. I also like the old adage, “If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not Zebras.” If I follow that advice, the answer is simple – the mystery flow came from common autumnal species that were in full view. These Fall plants are primarily asters and goldenrod.

Know this. Bob and I have had beehives on this spot for approximately 10 years. A flow like this one has never occurred. Yes, yes, I am fully aware that big flows come along occasionally. In fact, if you posed the situation that I have outlined above to me, I would listen intently and then speculate that you had a great flow from traditional plants not particularly known for great flows (in your area).

But you see . . .

During the same couple of months, I was getting correspondence from John H. an Alabama beekeeper whose colonies are 850 miles from this colony. He was observing that a good Fall flow was occurring from Elaeangus species. In fact, there were some blooms bleeding over into December. My Elaeangus species here in Northeast Ohio bloom in the Spring through late Spring. My colony was trashed by bears on June 20th or so. For the desperate bees to profit from that flow seems late for a surplus from Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellate) that normally blooms in March-April. Did that flow go well into June? That’s a stretch, but making nearly a full deep of honey from routine sources from June to December is a stretch, too.

But I do know this . . .

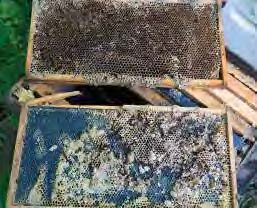

My colony that looked like this June 27, 2018

This is what the colony looked like on December 7, 2018

This is what it looked like inside the hive on December 7, 2018

It only gets more intriguing . . .

It’s clear by now that I don’t really know from which plants the pollen and nectar flow came, or the dates that the flow was available to the bees. I thought the colony was dead. It was essentially abandoned. Until this colony does something else, my saga ends at this point. I do plan to put some extra stores on the deserving colony in late January to early February. Again, since I am now un-nerved, maybe I should just leave it to fend for itself. It’s done fine so far.

Final thoughts and considerations . . .

- Did this colony do well, in part, because it was isolated? No robbing. No drifting. No swarming (this season – at least)

- Did this colony do well because I was not a “helicopter” beekeeper. Other than by the bear, the unit was never opened at this new site.

- In the two years that it has been in my life, this colony has never been treated for mites. Did the complete setback in June disrupt mite biology?

- Did this colony do well because all its honey stores are recent and fresh – not the reserve stores that I hold back from the previous season?

- Was this colony just very lucky. After all, it (apparently??) did not lose its queen. Or did it? Could it have possibly been queenless and that allowed the foragers to store some surplus stores before the demands of brood feeding started.

- Should I practice more “out-of-sight out-of-mind beekeeping?

- I don’t know. But I do know that this colony should not be alive. 8. I do know that I will not forget this colony – ever.

Please note . . .

For the first time in a while, I have written a bee article that has a happy ending. Cheers for me and the rogue colony.