Investing In Forage For The Future

Investing In Forage For The Future

A Call To Blooms

By: Toni Burnham

Though many of us came to urban apiculture as almost a “call to arms” on behalf of pollinators in general and honey bees in particular, with Spring arriving I’d like to encourage city beekeepers nationwide to undertake a reinvigorated “call to blooms” (if you can possibly forgive that turn of phrase!) There just couldn’t be(e) a better time!

Just think about it: one of the reasons we often see a double take from people when we tell them about being an urban beekeeper is simple: most folks just don’t think of the city as a flowering place. Though in an earlier article or two (Bee Culture, October 2013) we showed that most North American cities feature adequate tree cover to support existing and additional beekeepers for quite a while, we don’t think this is any time for us to (ahem) rest on our Laurels.

Reason number one: they are what they eat

Even though there’s good stuff for pollinators to eat in the city, it is nonetheless completely reasonable to keep taking a look at the health and strength of the green spaces available to your bees, and to continue to improve the habitat in which we place our hives. More so than country bees, city colonies make up their diet from a wider range of smaller sources and may benefit from superior nutrition in many cases, compared to rural or suburban near monocultures. We can continue to expand the buffet on offer. The Spring (i.e. now) is absolutely the best time to make plans to boost the green cover and forage potential of your downtown landscape, and maybe to enlist many of folks who could not get into your short courses and other cool allies in the effort.

Reason number two: they aren’t the only ones in town

Also, the jury is still out, among native pollinator advocates, about whether the introduction of managed bee colonies to cities does not place additional competitive pressure on feral species. In an interview with renowned native pollinator expert Sam Droege of the USGS Patuxent Research Refuge (Bee Culture, December 2013) of the message for a beekeeping environmentalist can be hard to hear, but with some inspiration nonetheless: “…[T]he presence of honey bees is either going to be negative or neutral for native bees, and not a positive. It could be a neutral impact, but if resources are constrained, there is competition. When there are superabundant resources, the case gets murky, especially at different times of the year.” So let’s work on that abundance thing.

Reason number three: most of us are already teaching about forage anyway

Almost every short course has one (or a half-) lecture, kind of close to the end, where basic information on the key contributors to the local nectar flow is presented, along with a month-by-month overview of the local blooms. If you have gardeners in your club, you may be expanding that to even more information about bee-friendly wildflowers and landscapes. Sometimes a helpful list is distributed. This is all good, but it would be even cooler to see this sharing of information turned into a call to action.

The London Beekeepers Association offers custom seed mixes to promote pollinator forage in the city. (photo by Tara Moore with permission of LBKA)

It can really help. Back in 2013, beekeepers in London (England) went public with how the amazing growth of city beekeeping might be outstripping the capability of their Plane tree-based, pollinator-unfriendly street plantings to support all those colonies. They made this problem known not to dissuade people from making room for bees in the city, but to basically make more room. The London Beekeepers’ Association, which now has a Chief Forage Officer, Mark Patterson, in addition to the usual board members, started suggesting that people who wanted to add a hive to the cityscape needed to consider adding a chunk of pollinator friendly planting, too, and included bee forage gardening in their short course instruction along with packs of seeds and substantial planting guidance on their website (www.lbka.org.uk/forage.html).

This is a winning idea for all of us. When potential corporate sponsors who wanted to do something for the bees approached the association for hives, the latter were asked instead for places to plant, funds for seeds, volunteers to get those plantings done, and support for academic research into useful plant mixes, potentially usable by towns and cities to replace comparatively useless municipal displays of bedding plants and grass.

Reason four: you can box it up and take it home

Here in DC, we are working with the folks at the USDA’s Peoples Garden on an idea about planting window boxes for pollinators, because almost everyone has a window, though the same approach can be used for container or “square foot” gardens of all sorts. Clearly, a single window box won’t make much of a dent in the estimated 100 pounds of pollen and 500 pounds of nectar consumed by a typical colony in a year, but a few thousand of them sprinkled across a variety of urban neighborhoods can bias the habitat in a helpful direction. We talked to Sam, above, as well as other bee nutrition sources to develop some helpful guidelines in planning a pro-pollinator window box:Use “real,” preferably native plants for your region. Hybridized nursery plants often have sterile or nutrient-free flowers.

- If you opt for non-natives, take a look at plants that bloom during times of dearth or stress for your bees. Anything you can do to reduce robbing and build stores is good for your neighbors.

- If you are avoiding neo-nics, you might want to start from seed.

- Use several different kinds. Bees get nectar for energy and pollen for protein from flowers, but each bloom offers only a portion of what they need.

- Use plants that bees can “see.” The lighter the color, the easier it is for them to find. Go for white, yellow, pink, lavender, pastels, but stay away from reds and deep colors.

- Include some plants for you! Bees love many kitchen herbs that can make it into your diet as well, and these plants are often long blooming perennials: thyme, oregano, sage, chives, lavender (!!!), fennel, rosemary, and catmint.

- No flower will attract all the different bees – there are 2000 species in North America! – but each one is good for someone!

Reason five: fun we can have with non-beekeeper friends and allies

Reason five: fun we can have with non-beekeeper friends and alliesEvery year in April or May, we get phone calls from folks who are interested in learning about bees, but we have little to offer them. Our short courses take place in late Winter and are often sold out by early December. These folks are often gardeners, who got the “bug” while they were out turning over the soil for the first time this year. Enlisting them in pollinator planting, and teaching about forage for honey bees and others, gives them a handhold in our world and builds bridges way beyond the numbers of folks we can get into a hive in any season.

It’s also a useful science lesson for kids of almost any age, and appropriate for community gardens, rec centers, churches, schools, parks and many other locations in every city. The time they spend nursing up some flowers and watching avidly for a pollinator or two to come by builds advocacy and a useful basis of experience for future study of beekeeping.

Also, if you have any Master Gardener friends of bees, you may be able to work with them to create a locally appropriate pollinator seed mix: these do not have to be fancy, and they can even be a fundraiser. Consider a seed bomb building session using these materials, as well: though be careful where you throw (Bee Culture, October 2013).

Reason six: there may be more public opportunities soon

Reason six: there may be more public opportunities soonAt the recent NAPPC conference (Bee Culture, January 2015), Michael Stebbins of the White House Office of Science and Technology got many of us deeply excited by the news that part of the impact of the June 20 Presidential Memorandum on Pollinator Health was the opening of federally managed buildings and lands to pollinator friendly planting and landscaping practices, a change which has apparently captured the imagination of involved officials across the full range of agencies and settings. As a hint of what is possible, in places like San Francisco, where the Green Landscaping Ordinance requires planted offsets and climate-appropriate plant choices, “pocket park” and screening plantings have made helpful contributions to pollinator forage (even though SF is probably heaven for bees anyway!) Though much of the 650 million acres or so managed by the government (28% of the country, according to the Congressional Research Service in 2012!) is already rural or park land, the General Services Administration owns or leases almost 10,000 buildings nationwide, a large number of these within towns and cities. These enormous resources for pollinators are coming very nearly to your back yard if we make sure this happens, and we can keep an eye out for the Pollinator Task Force report due this Spring, and to both monitor what takes place near you for its impact on your bees, or to provide feedback on what you would like to see, including possible involvement and access. The Task Force has emphasized that public-private partnerships are a key element in this work, and we need to raise our hands if we want to get in on it.

Final reason: knowing more about the world of plants and bees makes you a better beekeeper

My job as an urban beekeeper is to try to understand my bees’ needs in such a way that they survive and thrive, and also that they make a net contribution to the lives going on around them–human, pollinator, plant, and more. The more you can learn about and improve the green spaces they explore, forage through, communicate about, and depend on, the more you can understand what they are up against, how these marvelous little creatures work, and what you can do on their behalf. Selfishly, some of my most-fun conversations are comparing notes with local beeks on what is blooming, what’s going on with hive weight as a result, how the last season seems to be impacting this one, and how it all resulted in more or less swarming, survival, supercedure, harvest, pests, delight, you name it. When you spot a need, or even just a nice-to-have (like something that actually blooms in August around here), you can move from observing to acting on a whole new level, one with mud on your hands and some kitchen herbs outside your window!

Toni Burnham keeps bees on rooftops in the Washington, DC area where she lives.

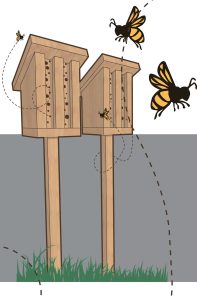

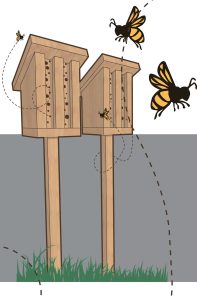

Winter Project: Make Your Own Bee Hotel

The architects at Sustainable.TO in Toronto recognized that the problem of urban sprawl could create an opportunity to build habitat for pollinators. They therefore used their design skill to come up with the concept of Bee Hotels, architecturally awesome sustainable resting and nesting space for solitary bees that ended up winning the NAPPC 2014 Advocate for Canada Award. The firm emphasizes that these species make up more than 90% of the bees we find around us in North America. Another bonus: these “resting places” for bees are not considered hives, and are therefore not regulated under strict city beekeeping rules!

The firm designed several different kinds of bee hotels: some were “street side” models designed to be located in the soil beds around Toronto’s 600,000 street trees

They also created “Park-Scale Bee Villages” for location in downtown parks. Made out of recycled wood from shipping pallets and the frames of demolished homes, the “villages” provide larger-scale multi-level habitats that can also connect with community garden and education activities in parks. In a way, the Bee Hotel that they built for the top of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel is like one of these: it has many different shelves which hold different types of nesting material attractive to different species. That gorgeous bee domicile has been visited by journalists, pollinator advocates, and even Prime Ministers!

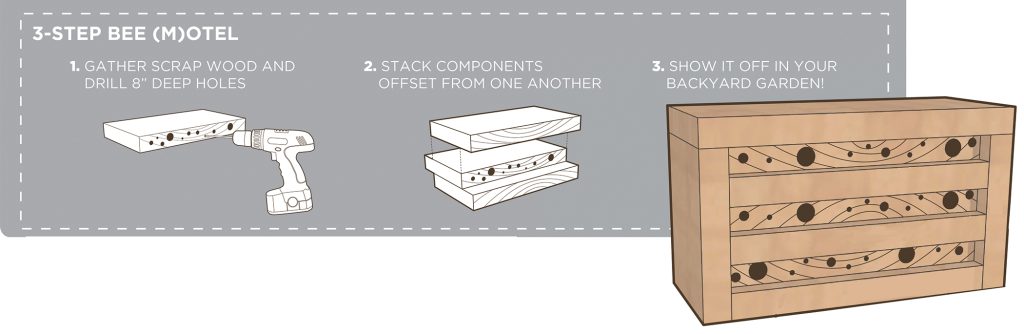

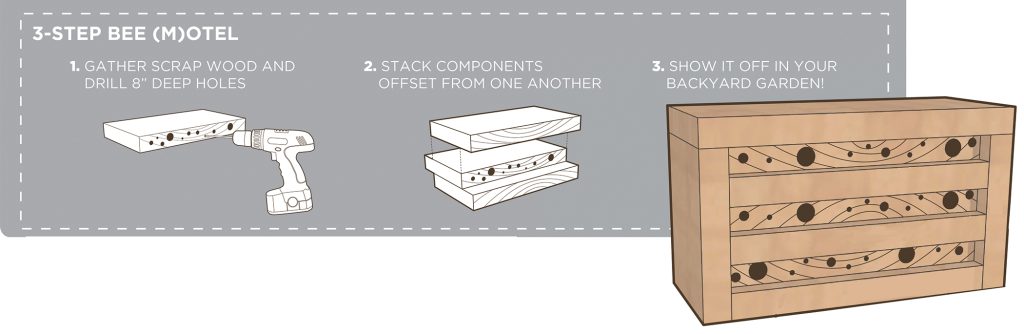

But anyone with some backyard or balcony or roof space can consider building a basic Backyard Bee Motel! You need to start with untreated wood: scrap or recycled lumber that has not been treated for water or pest resistance should work. The Sustainable.TO design offsets each board slightly from the next level, stacking and bundling the wood and then drilling 8” deep holes randomly in the front surface (see illustration). Their design features holes of several different diameters, appropriate to the preferences of a variety of species: experts recommend a range for 2 mm to 10 mm. It is compact, attractive, and has a foot print that you can choose to suit your available space.

In most of North America, solitary bee species emerge and are active as their plant partners come into bloom. The off season is an excellent time to build habitat and to increase the variety of native pollinators sharing space with your bees!

Investing In Forage For The Future

Investing In Forage For The Future

Reason five: fun we can have with non-beekeeper friends and allies

Reason five: fun we can have with non-beekeeper friends and allies Reason six: there may be more public opportunities soon

Reason six: there may be more public opportunities soon