By: Karen Fleur Tofti-Tufarelli

The royal jelly-producing glands of bees exposed to Round-up® experience premature aging, according to a Brazilian study published online. Round-up® is a widely-used glyphosate-based herbicide; many other herbicides are also glyphosate-based.

The study used the commercial formulation of Round-up® in order to simulate real commercial conditions.

The study was released around the same day in early August that a California Superior Court awarded a former school groundskeeper $289 million, finding that Round-up® contributed to his non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to various media reports.

Tara Cornelisse, a Senior Scientist with the Environmental Health Program, Center for Biological Diversity in Portland, Oregon, said that the Round-up® verdict against Monsanto was a “game-changer.”

Cornelisse said that while “the science has been showing (glyphosate-related) impacts on honey bees, habitat, and people, Monsanto (persists) in calling Round-up® safe while the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) continues to allow its use across the country.” ( In 2015, Cornelisse said, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), found glyphosate to be a probable human carcinogen (http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/pdf/MonographVolume112.pdf).

“The verdict in favor of the groundskeeper “almost gives more tangible credibility to the truth — and maybe will encourage the public to hold the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) more accountable . . . ” Cornelisse said.

In the Brazilian study, six-day old bees exposed to Round-up® appeared as if they were greater than 25 days old. The result, she said, “seem(ed) to advance cell death or aging,” and is “not only an issue because bees may die sooner or produce less royal jelly in their lifetime, “ but (also) because of the transition of roles that honey bees undergo.”

Worker bees feed the jelly to all larvae for a few days but feed it continuously to future queens, Cornelisse said. Then they transition from “nurse bees” — bees that take care of larvae — to foraging bees, or those that go out of the hive to get pollen and nectar.

“The premature aging of the royal jelly-producing glands could make it likely that the nurse bees transition too quickly to foraging bees, leaving (fewer) bees taking care of the brood, potentially reducing the brood, or number of offspring,” Cornelisse said.

Further, this reduction (19-days+ plus) in the lifespan of the honey bee is a “big deal,” according to Cornelisse, as the lifespan of a honey bee is relatively short, ranging from only three to four weeks in the summer to four months over winter. (Bees foraging for nectar in the summer, said Cornelisse, are more susceptible to dying from factors such as pesticides, predation, parasites or disease than those overwintering.)

Though the actual number of bees tested was small, Cornelisse noted, it should have been enough for microscopy tests, she said. The difference in cellular structure was “significant,” she said, “so that tells you that the sample size was sufficient to detect differences.”

The study —“Changes in hypopharyngeal glands of nurse bees (Apis mellifera) induced by pollen-containing sublethal doses of the herbicide Roundup,” Chemosphere (2018), doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.189) — was authored by Márcia Regina Faita, Eliana De Medeiros oliveira, Vieira Alves Valter, Afonso Inácio orth and Rubens Onofre Nodari.( https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045653518314553.)

Research hives used in the study were well-established, said Cornelisse — “a good thing,” as the researchers “know what they’ve been exposed to for a while and could control their exposure.” (Before beginning the study, hives were managed for six months to provide homogeneity with the breeding area,)

Though the amount of royal jelly produced did not decrease with Roundup®, the study found, those hives that received food containing Roundup ® presented an average weight of royal jelly lower than that of control hives (0.167 g and 0.287 g per queen cell, respectively); but this difference, the study found, was not statistically significant.

The study authors noted, Cornelisse said, that it will be important to analyze the nutritional quality of the actual royal jelly produced to see whether its chemical make-up changed with Roundup®.

While a few previous studies have looked at the effect of glyphosate-based herbicides such as RoundUp® on bees, Cornelisse said, this is the first study that looked at RoundUp® on royal jelly (and thus queen bee) production.

Cornelisse said that while there has been much research on the link between herbicides killing plants that bees need for their foraging, the Brazil study findings “will jumpstart some other research on the impact of herbicides on insects, because we haven’t been paying much attention to that and it’s really important.”

But the spraying of glyphosate-based herbicides such as Round-up® affects not only the health of honey bees as shown by the research, but also honey itself.

EPA documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by U.S. Right to Know — a consumer advocacy organization — also show that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has found residues of glyphosate in samples of U.S. honey. Some samples, according to Right to Know, showed residue levels double the legally allowed limit in the European Union.

In May 2018, Right to Know filed suit in Federal District Court against the EPA seeking documents related to EPA’s interactions with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding the residue testing for glyphosate, communications EPA has had with Monsanto regarding that testing, and EPA compliance with a FOIA request filed in February 2017 seeking records between EPA employees and CropLife America, a trade association for the agrochemical industry.

Given these recent results showing the negative impact of RoundUp® on both honey bee lifespan and honey itself, “the biggest thing we can hope for right now,” Cornelisse said, is that the public can wake up and realize the EPA is approving the use of (RoundUp®) all over the country — millions of pounds — and maybe this will put pressure on the EPA to carry out their mandate – their mission – to protect human health and the environment.”

##

Meanwhile….

By: Peter Dockrill

Scientists aren’t entirely sure why honey bee populations are stessed. Strong evidence exists linking the decline to pesticides, but new research shows another poison – one long believed to be harmless to animals – may actually be indirectly killing bees.

A study by researchers from the University of Texas at Austin suggests the world’s most widely used weed killer – glyphosate – could be a previously unknown factor behind what’s going on.

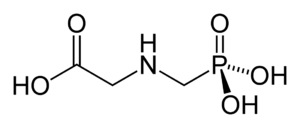

Glyphosate is the active ingredient in Monsanto’s best-selling Roundup – the self-proclaimed “flagship” of the company’s agricultural chemicals business.

That’s quite a business too: a 2016 study found that since its introduction in the 1970s, almost 10 million tonnes of glyphosate have been sprayed onto fields the world over.

That’s a lot. Especially when this herbicide may be killing more than just herbs.

“We need better guidelines for glyphosate use, especially regarding bee exposure, because right now the guidelines assume bees are not harmed by the herbicide,” says one of the researchers, biologist Erick Motta.

“Our study shows that’s not true.”

Glyphosate’s mechanism of action as a herbicide is the disruption of an important enzyme found in plants and microorganisms, which is located in a metabolic structure called the shikimate pathway.

Animals don’t have this pathway, which is why the chemical has long been thought to be non-toxic to them. But what about smaller organisms, such as the gut bacteria that populate the bee microbiome?

Contemporary science is basically an avalanche of studies revealing how gut bacteria and the microbiome generally are an essential and complex part of overall health.

In bees, it looks like the same holds true.

When the researchers exposed honey bees to glyphosate at levels equivalent to what’s been found in crop fields, gardens, and roadsides, it significantly reduced their healthy gut microbiota.

In the experiments, half of the dominant healthy species of gut bacteria in the exposed bees – including Snodgrassella alvi, which help the insect process food and defend against pathogens – were found to be reduced.

This reduction of good bacteria didn’t end there: it actually impacted bee survival.

When untreated bees and glyphosate-exposed bees were exposed to the same bacteria – an opportunistic pathogen Serratia marcescens – the survival rates were starkly different.

Bees that hadn’t been exposed to glyphosate saw their numbers halved after eight days with S. marcescens. But only one-tenth of the glyphosate-exposed bees survived the pathogen after the herbicide.

“Studies in humans, bees and other animals have shown that the gut microbiome is a stable community that resists infection by opportunistic invaders,” says senior researcher and evolutionary biologist Nancy Moran.

“So if you disrupt the normal, stable community, you are more susceptible to this invasion of pathogens.”

The pharmaceutical giant Bayer – which now owns Monsanto – issued a release in response to the research, claiming “[no] large-scale study has ever found a link between glyphosate and honey bee health issues” and that the new paper “does not change that”.

That’s predictable, but according to other researchers, it also might be missing the point.

“This study is part of a growing trend towards looking at more complex interactions between animals, their microbiome, and interacting stressors,” explains evolutionary ecologist Andres Arce from Imperial College London, who wasn’t involved with the research.

“Understanding these interactions is essential to quantify the hazards associated with pesticide use and is essential if we are to develop strategies that allow us to continue using pesticides, which are vital to modern agriculture, whilst minimising their effects on the natural world.”

For now, more research is needed to better understand how glyphosate is affecting the bee microbiome – and the health of other creatures too – but the researchers say we should no longer think of this herbicide as being harmless to animals, even if it’s only one factor affecting honey bee health.

“It’s not the only thing causing problems,” says Motta, “but it is definitely something people should worry about because glyphosate is used everywhere.”

The findings are reported in PNAS.