by Larry Connor

Early on in your pre-beekeeping planning, you should carefully evaluate all your potential apiary locations. Evaluate location options with a mentor or another experienced beekeeper before locating bees in your back yard or friend’s backyard, review these items, and address the suitability of each one. Use the number of colonies you want to start as one of the criteria you use to evaluate a site. I recommend all new beekeepers set up a minimum of two to four colonies, and a maximum of 20-24 colonies during your first season. The lower number fits into a sustainable concept where colonies help each other in a time of need, while the larger number will help you both optimize your time and investment but unfortunately will also increase your risk.

Hazards to Humans and Animals

No apiary should be established where there is a potential for doing harm to humans, animals or the bees themselves. First, some bee biology; when bees are young, they make orientation flights around the front of the entrance of the hive as a means of learning the location of the colony. There are often a large number of young bees that do this at the same time. Some beekeepers call this ‘play flight’. All bees must make these orientation flights in order to successfully return to the hive, including young queens and drones. For some people, the sight of several hundred bees in the air in front of a hive can be unsettling. These bees are no more likely to sting than bees on normal flight, and maybe less so, since these are young bees. Beekeepers who have not seen this behavior will mistake it for swarming, which it is not. When non-beekeepers see this behavior, they might think that an attack is about to start. It is not, but how would an inexperienced human know that fact?

While you may think it looks pretty to have your hive at the edge of your vegetable garden, some of the bees will return to the hive by flying over the garden where you are working, get tangled in your hair and cause an accidental sting. This is not the same as the bees foraging on your cucumber flowers or working the borage; those bees will rarely cause you any problems and you probably will not notice they are there. In selecting an apiary location, carefully consider others who will be working and playing in the area, especially children, those with limited mobility, and animals in confinement.

Sun Exposure

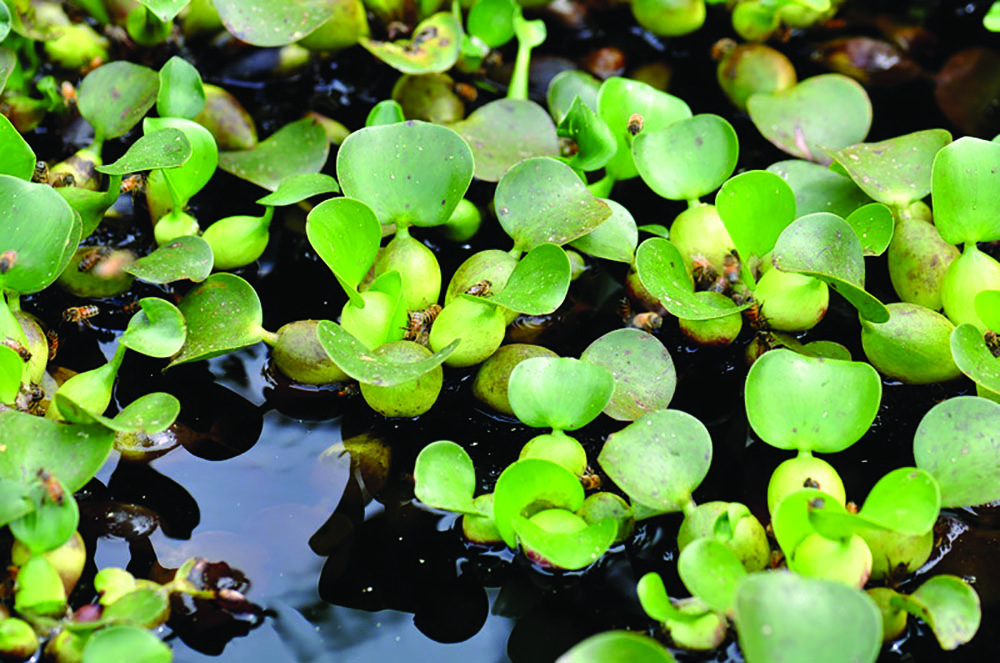

Providing an attractive water feature that also provides water for honey bees will eliminate problems with neighbors and their swimming pools, as well as minimize exposure to pesticide residues.

How Many Colonies?

Your community may set a limit on the number of colonies you can keep on the property you own, based on lot size and other rules. Let’s say your city guidelines limits you to four colonies. You can manipulate that number a bit by using double nucleus hives (two queens that are side-by side in divided boxes on one hive stand). Or you may have mating nuclei that are not as strong and powerful as full-sized colonies. You might make up nuclei during the late Spring and Summer and sell them or move them to an out yard for final development. That will keep you colony count within the spirit of the guidelines.

If you have an apiary location in the country, your primary limiting factor will be the amount of forage for the bees throughout the season. Some locations may be very good for Spring buildup and an early nectar flow, but then become a food desert that causes the bees to consume their stored food as well as steal food from each other. Other locations may have productive nectar production for a few weeks every year, and then become and area where it is relatively difficult to keep bees. In a heavily forested region of New England I have seen apiaries with as few as four hives – any more than that will not increase total honey production. In areas of diverse forage and generally good beekeeping locations, I find that yards between 12 to 30 colonies are possible.

As you expand into a new yard location, start with a smaller number of colonies and, over time, build the holdings as experience shows that the site can support more bee colonies. There are sweet clover locations in the Midwest that can handle 30 or more colonies quite well but only during the clover flow.

Locations may be very good for Summer nectar collection but not at all suitable for wintering. You want to avoid locations with extreme wind exposure, risk of vandalism from hunters and snow machine users, or are nearly impossible to visit and feed during January and February. You will want to visit the colonies during the Winter to evaluate their weight for remaining honey and feed as necessary. If you have deep snow you may end up using snowshoes and a sled filled with winter sugar patties to put on the bees to prevent starvation.

Some clever beekeepers put a group of bee colonies on a trailer that they can move to pollination sites and honey production areas. At the end of the season the bees are returned to a permanent apiary where the colonies are placed on the ground, fed, protected for Winter, and watched carefully.

Bee Forage

Honey bees do not visit every flower species Nature produces. They rarely visit tomato and related flowers because they do not buzz pollinate the flower like bumble bees to obtain pollen. It confuses new beekeepers to see vast expanses of flowers in full bloom and not find a single honey bee visiting them. Sometimes the flowers are covered with pollinating fly species, and other times there may be a predominant species of native bee on the flowers. This is where a good teacher/mentor will be a great help to the new beekeeper, as will selected reference books.

There are an estimated 20,000 species of bees in the world, and the honey bee is only one of them. Different races of honey bees that have evolved to pollinate plant species found within their native habitat. For example, studies in Europe showed that Italian bees (Apis mellifera ligustica) were more attracted to citrus flowers than bees that had no selective time together with Citrus. Similar differences in daily flight time were found between different races of bees in the African desert. It if sounds confusing, it is, and there are many specialists who have spent their entire careers trying to unravel this complicated puzzle. There is much more to learn about bees and flowers, a field called Bee Botany. In the United States, these races have been interbred to such an extent that it is hard to discriminate traits.

For the sustainable beekeeper, knowledge of the plant species and even varieties or cultivars of certain plants will be extremely valuable. Since the honey bee is not native to the Americas, it has a competitive relationship with other pollinators. Generally, this competition makes both the honey bee and other bee species work harder to collect pollen and nectar, which is beneficial to the plant needing bee visits for pollination.

Many agricultural and garden flowers are also introduced to the Americas. Some, like apples are widely embraced by human culture while others, like spotted knapweed (Centaurea spp) and purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), are highly regulated in some areas and subjected to biological control agents introduced for their control. Since honey bees are generalists – visiting a wide range of species – they benefit this floral smorgasbord as pollinators while benefiting themselves while filling their hives with surplus honey and pollen.

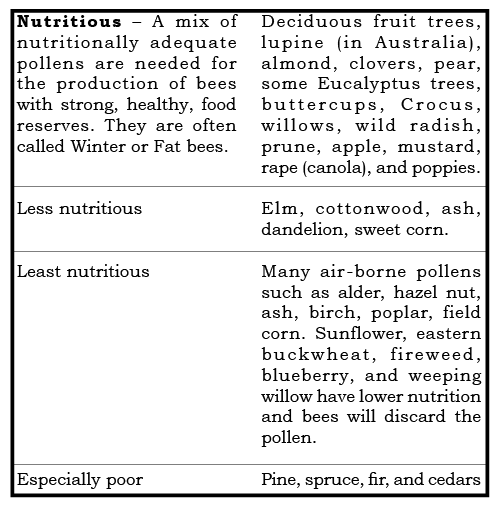

In a future article we will discuss the pollen and nectar producing plants important to bees and beekeeping, and the general colony management plans for the area. We know that not all pollen sources are the same, and here is a simple summary:

Foraging Distance From Hive

It is beneficial to honey bee colonies to be situated near a major nectar source because it costs the hive less energy, in terms of honey, to launch tens of thousands of worker bees to a nearby location than a distant location. In diverse forage environments honey bee workers fly routinely two to three miles to obtain pollen and nectar. This is an efficient foraging distance where the cost of flying the forager to the flowers still pays back with a positive nectar/pollen load. As distances increase, the flight becomes more costly for the colony. One California research study showed that honey bee foragers flew four miles for a very rich nectar source, passing over poorer nectar sources just two miles away. In the U.K. 10 percent of the bees on heather flew nearly six miles for forage and the average bee flew 3.4 miles. Reports of bees flying ten or 15 miles to forage may be an exaggeration or a reflection of a complete lack of food of any energy composition.

As you evaluate a potential apiary location, use an Internet map image or a traditional printed township map to draw circles around potential apiary sites. Draw circles with a radius of two miles, one at three miles and another at four miles. The two mile radius should be used to determine where rich sources of food are available. The four mile radius should be reviewed for potential problems with chemical exposure, diseased colonies or any potential hive disaster. It can be pretty shocking to see the wide range of risks bees face with their wide foraging range.

Water supplies should be within half a mile of hives, and preferable within the apiary. As temperatures increase, the percentage of bees collecting water increases. At extreme temperatures (above 105°F) the colony is primarily seeking water. Use a water feature using tropical plants to establish an attractive water source you can enjoy as well, especially in your backyard.

Flood and Fire Risk

Many potential apiary locations run the risk of high water during spring flooding during snow melt and seasonal flooding. During dry periods the risk of high water in a particular location may not seem to be great, but in areas where droughts have been routine for a number of years, during which beekeepers have set up and run bees for several seasons, a return to normal moisture level will increase the chance of flooding from a local stream or lake. Moderate flooding with the bottom boards covered with water can be tolerated if the bees have a good upper

entrance. But where water rushes through and carries hives down the river, these locations must be avoided at all costs.

During extremes in dry weather, there is always the risk of a forest or grass fire. Keep bees out of extremely high risk areas and put bees in less risky locations, such as in the middle of a fire lane or vegetation free region to reduce the risk of fire. Even suburban small-scale beekeepers loose colonies when a trash burn gets out of hand and burns their colonies.

Pesticide Exposure

As we learn more and more about bee deaths, outright or indirect, we learn that there are many compounds being used in the environment that negatively impact the colony. When setting up your apiary, check for use of routine chemicals in agricultural crops, around golf courses and corporate headquarters where all sorts of pesticides are used in great abundance. Even the water coming off the lawn may be toxic to bees searching for fresh water.

I’ll Bee In Albion! Join us at the 150th anniversary of the Michigan Beekeepers Association and the Heartland Apicultural Society in July.