By: Peter Sieling

Visiting with the Cogshall Brothers and G.M. Doolittle.

Many years ago, my dad, the first beekeeper I ever knew, took me to the barn early one morning to milk the cows. We lived in the Lake Ontario Snow Belt and the snow was pretty deep for a four-year-old. Dad walked ahead of me. Looking back he saw me leaping from one of his footprints to the next, trying to match his stride and fit my little boot prints in his.

Many years ago, my dad, the first beekeeper I ever knew, took me to the barn early one morning to milk the cows. We lived in the Lake Ontario Snow Belt and the snow was pretty deep for a four-year-old. Dad walked ahead of me. Looking back he saw me leaping from one of his footprints to the next, trying to match his stride and fit my little boot prints in his.

Fifty-five years later, I again attempted to follow the footsteps of giants. In 1890 and again in 1897, Ernest Root, editor of Gleanings in Bee Culture packed his Sunday clothes, stuffed a veil in his back pocket, and strapped a “Kodak” under his bicycle seat. He wanted to meet some of the New York beekeepers and discover the secret to their large honey yields. His journey, by train and bicycle took him zigzagging across New York State.

While reading through old issues of Gleanings in Bee Culture, I found a couple old photos of the Coggshall and Doolittle houses. What had happened in the last hundred years? Their houses may have fallen into ruin, burned to the ground, or been altered beyond recognition. I decided to try to find them.

Armed with two photographs and descriptions of the neighborhood, my wife Nancy and I packed a lunch and set out to visit the former houses of the Coggshalls and G.M. Doolittle. Both lived in the eastern Finger Lakes region. We live at the southwest edge of the Finger Lakes. Our plan was to circumnavigate the Lake region and search for their homesteads.

In the gay nineties (that’s 1890s for all you kids under 50), New York State was one of the largest honey producing regions in the United States. Several of the largest and most progressive honey producers lived in the Finger Lakes region and east. It was buckwheat country. In 1897, Ernest Root exclaimed, “. . . New York State has more beekeepers to the square mile (I was about to say to the square inch) than any other place on the globe. I have been in locations where from one hilltop could be seen as many as 5,000 acres of buckwheat fields – counties where there were all the way from 2,000 to 3000 colonies!”1

There is still a lot of beekeeping and a rich history in the Finger Lakes. Between Keuka and Seneca Lakes, we detoured north to a Mennonite bulk food store. Their shelves were stocked with Wixon honey, a multigenerational honey and beekeeping supply company. My dad bought his supplies there in the 70s and I buy supplies there now. We drove southeast across the plateau and down through Watkins Glen, familiar to race car fans. Watkins Glen sits at the southern tip of Seneca Lake, the deepest of the Finger Lakes. It never freezes over and I have been told that people come from miles around to fill their car radiators with Seneca Lake water to avoid the expense of buying antifreeze. If you believe that, I have a new patent hive I’ll sell you.

Rounding the end of Seneca and driving up hill away from the lake feels almost like taking off in an airplane. The next lake is Cayuga and as we descended out of the clouds (figuratively speaking) we saw Cornell University across the valley reflecting the sun like a “shining city on a hill”, its huge buildings looking down on the city of Ithaca in the valley.

Colleges and universities in New York are frequently built on hillsides. Why waste good farmland? At Cornell, a Bee Culture columnist, Dr. Roger Morse, taught a generation of bee researchers, professors, and full time beekeepers. I never met him, but as a young beekeeper I once wrote him a letter and I have his reply still tucked in one of his books – A Year in the Beeyard. I took beekeeping classes at Cornell under Dennis vanEngelsdorp, now at the University of Maryland. There was some talk of dropping the beekeeping program a few years ago, but funding has been restored and they are now developing a new beekeeping program. After rounding the tip of Cayuga Lake, we saw the County Cooperative Extension Building, the meeting place of the Finger Lakes Bee Club. They’ve asked me to lecture there twice, proving that either I’m not a horrible speaker or they couldn’t find someone else to talk.

We stopped at a visitor’s center, tucked away off the main highway, picked up some tourist brochures, ate lunch, and consulted the map. Was it Fate or Providence? The visitor center was on the road we needed to take. If we had flown past, we could have ended up in Cortland. Once more we ascended into the hills. We were aiming for West Groton, home of the Coggshall brothers, David and Lamar. By 1897, Lamar owned between 1,100 and 1,200 colonies in ten bee yards spread out over 40 miles. David had 600 colonies and with all his extra free time, did regular farming and poultry.

Ernest Root missed the Coggshalls on his first visit, but seven years later it was one of his main stops. Ernest said the Coggshall’s harvesting methods would “make a beekeeper’s hair stand on end”. They would typically harvest 3,000 to 5,000 lbs of honey in a day with nothing but a three or four man crew removing one comb at a time, uncapping with a single cold knife, and spinning them in a four frame extractor. Ernest called it the “lightning-kick-slap-bang-get there plan.”

If you want to try it yourself2, start with a sting-proof suit. The first man kicks off the cover, sending it flying to the ground. They used enameled cloth instead of inner covers. Pull it up on three sides, leaving the fourth edge stuck down like a hinge. Puff a cloud of smoke under the cloth and push the smoke down through the frames using the cloth like a bellows. That clears most of the bees from the super. I tried it and it works. Remove the frames one at a time, shake the comb, give it two swipes with a bee brush and shove it into an empty super on a wheelbarrow. Once the super is empty, kick it off with your foot. That knocks off the remaining bees. Now place that super on the wheelbarrow and fill it from the next super. The second man wheels four supers into the extracting building, a bolt together shack. A cloud of robber bees fills the room. Bees by the thousands fall into the extractor and drown. The third man uncaps the combs, and the fourth spins and draws off the honey until he reaches the layer of drowning bees. By the end of the day, there will be a three or four inch layer of dead bees floating in the extractor. They are dumped and the robbers carry the honey back to their hives to be harvested later or used for Winter food.

When Ernest visited he could hardly believe the cloud of stinging bees, but one of the boys later confessed that they might have stirred the bees up a bit for his benefit.

One of several articles on the Coggshalls in the 1890s shows a photo of the distinctive Eastlake style “house that bees built”. I wondered if we could find it. All we knew was the location was somewhere near West Groton. We had our car’s navigation system, a GPS, and a cell phone GPS all running at once, plus a map. Without a house number or road name, the modern devices were nothing but dashboard ornaments. We had to depend on the map, but West Groton was located in a crease.

After wandering up and down dirt roads, we managed to find Peruville, then Groton. I got local directions at the gas station. Five miles later we found West Groton Rd. and then an intersection, half a dozen houses, and a church. We drove two miles out of town, back tracked, two miles down the second road, and then tried the third road. There is was! It was like seeing the Emerald City for the first time. It has been kept up in beautiful condition. The current owners sell organic beef, eggs, and dairy in a store on site, so I didn’t feel too shy about stopping and knocking on the door.

Ed Scheffler, the owner came out. He knew the house used to belong to the Coggshalls and that they kept bees after someone invented a new hive. The only vestige of their honey business was in the attic – a cardboard comb honey box. He graciously allowed me to take some photos.

David and Lamar were active in beekeeping organizations, but they didn’t have time to write. Lucky for us, Lamar had a protégé, Harry Howe, one of his “lightning operators”. Off season, Harry built and sold bicycles, taught school, and managed a couple of his own apiaries near Cornell. He wrote several entertaining stories about the Coggshalls in the late 1890s. After studying entomology at Cornell, Harry moved to Cuba to become a full time beekeeper.

After the Coggshall’s we continued east toward the home of one of the greatest beekeepers who ever lived, G.M. Doolittle – the father of modern queen-rearing, and a prolific writer. We were following in the footsteps of beekeeping pilgrims from all over the United States. Doolittle had a lot of visitors.

We did not see Owasco Lake. Moravia, the village on the southern end is situated farther south because of the marsh flats. The village of New Hope, my childhood hometown, sits halfway between Owasco and Skaneateles Lakes at the top of the hill. There’s my old house, the church, and the store. The mills are boarded up. G.M. Doolittle and I were practically neighbors, separated by seven miles, forty years, and a lake.

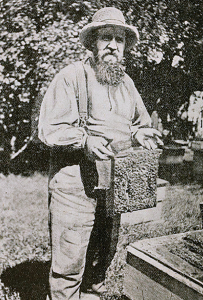

Doolittle’s life spanned 72 years, from 1846-1918. He gets a short paragraph in the ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture. There is much more, but you can only piece together fragments of his biography from his writings. As a boy Gilbert performed poorly in school. He showed a deep interest in honey bees from early childhood. His father, a farmer and part-time beekeeper with 20-40 colonies, prayed that Gilbert would fail at beekeeping and become a farmer. Gilbert persisted and became one of the most successful beekeepers, queen producers, and beekeeping teachers of his generation.

While the Coggshalls managed over a thousand colonies, Doolittle probably had fewer than 100, one home yard and one 30 colony out-apiary. He produced mostly section honey, what we would call comb honey. Doolittle practiced intensive management rather than relying on large numbers of colonies. In a poor year he would get yields of over one hundred pounds per colony and regularly harvested 200-300 pounds per colony.

Besides section honey, his specialty was queen rearing. Doolittle shipped queens all over the world. His techniques, described in Scientific Queen-Rearing, are still used today with only minor variations.

As an author, Doolittle wrote three books, and for almost 50 years wrote regular columns for seven beekeeping periodicals. He was a popular speaker at conventions. A devout Christian, he sprinkled his talks with scripture quotations and kept his listeners in stitches with his anecdotes.

I have learned much through reading his column, Conversations with Doolittle, written at the turn of the 20th century. For example, a bee in April is worth 100 in June. That’s because that bee nurses the larvae that nurse the larvae that will gather the honey during the big nectar flow.

A colony rich in stores produces more bees than a colony near starvation. A frame of uncapped honey inserted in the middle of the brood nest will stimulate the bees to move the honey above and the queen will fill the newly empty frame with eggs.

The brood nest should be wall to wall brood 45 days before the honey flow to have the maximum number of foragers when most needed.

Finally, something to “paste in your hat”. As you are leaving the apiary, turn around and look over your apiary to make sure everything is in “apple pie order”. How often I have left something behind and had to go back.

When R.B. Leahy, the Editor of The Progressive Beekeeper, traveled from Missouri, he mentioned meeting Doolittle’s pet squirrels, Daisy, Fawn, and Gladstone, who came out of the trees to eat breakfast on Doolittle’s lap. Ernest Root, seeing a telescope in Doolittle’s workshop, noted that Doolittle was also an amateur astronomer. To visit Doolittle, editor R.B. Leahy took a train to Skaneateles village, boarded a steamer south to the Borodino Landing, then hiked up the hill to town and hitched a ride with Doolittle’s wife at the post office. Ernest rode his bicycle southwest from Syracuse, coasting down Rose Hill Rd. until suddenly the Doolittle house appeared on the left. That’s what we had for directions.

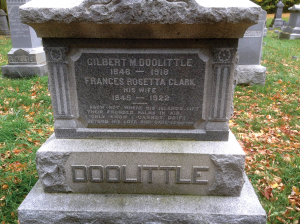

Nancy and I turned north on Rte. 41 at Scott, approaching Borodino from the south. Fifteen minutes later we stopped at the Borodino cemetery on the south end of the village. It is located on a steep hillside. Old and new tombstones leaned higgledy-piggledy along the narrow winding path made for horse-drawn hearses. Squeezing a car between tombstones felt like we were driving over toes of those resting in their graves. It was a perfect cemetery to wander through, on a windy night, clouds scudding under a gibbous moon.

We wandered among the tombs and after a few minutes of searching, Nancy found the monument of Gilbert M. Doolittle and his wife Frances. There were no other Doolittles in the Cemetery, as though he appeared out of nowhere and vanished into the mists of history. Doolittle died of “heat prostration complicated by contracting a severe cold”. He would surely have a different diagnosis today and would have lived many more years. “The voice of a great beekeeper-teacher has been stilled.”3

The epitaph on his stone is a stanza from John Greenleaf Whittier’s The Eternal Goodness:

I know not where his islands lift

Their fronded palms in air.

I only know I cannot drift

Beyond His love and care.

Borodino, consists of an intersection, a few houses, a church, and a store. We turned east on Rose Hill Rd. A couple miles out we saw a square, hip roofed house but no widow walk, with the right porch, and several outbuildings. I knocked at the door. It was closed up and silent as though no one lived there. We drove back to town, then down to the landing on the lake. Stopping at the store, an elderly woman was selling baked goods outside the front door. I asked if she ever heard of Doolittle. She referred me to the store owner who referred me to the town historian. No one that I asked had heard of Borodino’s most famous and revered citizen. A prophet is not without honor except in his home town.

With the sun setting we drove north to Skaneateles and west through the villages and cities at the heads of the Finger Lakes: Auburn, home of Harriet Tubman, Seneca Falls, the town on which It’s a Wonderful Life was modeled, and Geneva, where both in the 1890s and today you could attend the Geneva Bee Conference.

South of Geneva, we passed through Bellona, a dip in the road with a church and firehouse, once famous as the home of the Ontario Beekeepers Club, not to be confused with the current Ontario Finger Lakes Beekeepers. The Ontario Beekeepers spent most of the 1890s sending out letters and petitions to have Apis dorsata, the giant Asian honey bee introduced to the United States by the Federal Government. There was a big controversy over whether that was a good idea or not. A.I. Root, Ernest’s father, received several queens preserved in alcohol, and a beekeeper/missionary was on the lookout for colonies to put in a hive and ship halfway around the world. Some people speculated that these bees might not consent to being kept in boxes.

Did the Bellona beekeepers ever get their Asian honey bees? Did Doolittle ever convert from Gallup to Langstroth hives? Did Harry Howe make a success of beekeeping in Cuba? The answers may or may not be found. The internet contains the Big Book of Beekeeping History and there are a lot of pages, enough for a lifetime of reading.

1Gleanings in Bee Culture. 1897 page 672.

2I am not endorsing the Coggshall method. It was fast, efficient, and they made a lot of money, but it was rough on the bees. It is better to be a little slower and a lot more humane.

3Doolittle’s obituary. Gleanings in Bee Culture. 1918. p.397