By: A.I. Root

At the national convention in Cincinnati in 1882 I had announced that I would take a foundation mill with me and that I would make comb foundation before all who cared to see. Mr. Muth gave me a barrel of nice beeswax and one of his honey extractor cans and we had a steam pipe attached to the apparatus for melting. As soon as the wax began to melt, curious people gathered around, for the convention was held at an exposition.

“Is that maple sugar?” asked one onlooker, and at the word, everybody else began to walk over toward me. Did you ever see bees start over to a place in a hive where a new queen had just been run in? Well, I seemed to be the new queen, but I did not want to be just then, for I was not ready, and the man who was to bring in the foundation mill had not come yet.

By this time a crowd had collected. As usual, when anyone brings something to an exposition, people expect to see something nice or funny, or else, why should it be brought? Someone in the crowd picked up the wax and wanted just a little piece to wax thread with, but you see it was not mine to give away. They got in my way, and wondered if that was water in my tub until I began to feel almost cross, but I just looked pleasant and talked while I stood behind my stand and dipped wax, and wished and wished that the man would come with the mill, as he had promised to do. It was half past two, the appointed time we had agreed to make foundation and everyone was looking at the plain sheets of wax in a disappointed way.

“The machine will soon be here to make the cells in the sheets,” I kept saying, but while I said it, I kept fearing that something would go wrong, and that it would not come. Finally, however, it arrived, and was set down on the stand. Before I could turn some one had run a card through it just to see what it would do. I was horrified for it once cost me a ten-dollar bill when a child ran a piece of tin through one of the mills. While I was explaining to the thoughtless friends that it was a very dangerous thing to do with such a machine, some one else who was not listening, ran another card through. By a stroke of wit, I unscrewed the crank and took it off.

All Because I Could Not Make Starch

Then in a nervous, fidgety way I began preparations for making starch to lubricate the mill. I put some water into a pail, stirred in some starch, put it under the steam, and nervously waited for it to get thick. I made it so hot that it burned my fingers, but it was just harmless milky water and nothing more. The people were so eager, I feared every moment they would be rolling sheets of wax through without any crank or starch. I asked if any one in the crowd could tell me how to make starch. Not a man there knew how. I began to doubt whether there was a man in the state of Ohio who knew. I had just got up courage enough to ask a lady who stood near how to make starch, but she walked away. I put on my most winning smile and turned to another one.

“My friend, will you be so kind as to tell me how you ladies make starch?”

Not a word.

“Just a common starch, such as you ladies starch clothes with?”

She looked as if she had no ill will towards me at all, but offered not a word in return. I began wondering if this were not really a fairyland in good earnest. I looked around for a friendly face. Not one did I see.

“Why, that woman is deaf, she can’t hear a word,” said a bystander, and that unraveled the mystery. At this moment a friendly face did come into view. It was Prof. Cook and wasn’t I glad to see him! He asked me if I had boiled the starch and I said yes, but I was not real sure. He just put the steam pipe down into the starch and made it boil and then it was thick and starchy, to be sure. I made up my mind I should never scold anyone after that for being thick-headed.

By the aid of the starch the $25.00 mill rolled beautiful foundation the very first time and a friend who saw how hindered I was by the crowd invited me to come inside his enclosure where an iron fence kept the crowd away. Another friend sat down with a penknife and cut the foundation into little pieces and distributed them among the crowd.

I came pretty near falling in love with Cincinnati. I loved her children and I loved her men and women, and I felt that I could love even those who sold so much beer and tobacco.

Before I got through someone rolled a piece of dry wax through the Mill so it could not be used any more until I got home.

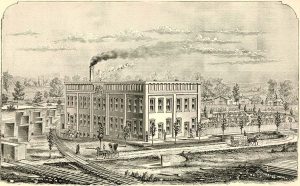

The Warehouse Fire

It was Sunday evening, March 7, 1886. I sat at my desk reading the Sunday School Times, and I noticed that the lesson for the following week was from the book of Esther, so I took my wife’s Bible and read the book of Esther clear through. By that time I was getting so sleepy that I thought I would go to bed. The print in her Bible was rather fine, but for all that I had not used spectacles up to that time, even though I was then 46 years old. Maybe the fine print made me drowsy before my usual bedtime. It seemed but a short time until my wife startled me from a sound sleep by asking what that light was out of the window.

“Why Amos, there is a great fire, and as true as you live, it is our warehouse.”

I remember she said something about the poor horses and our Jersey cow, and as I sprang from the bed wide awake in an instant, I meditated running to the scene of the disaster without dressing at all, but in a small part of a second I decided it would be better to clothe myself so I could stand the weather even if some time were lost. Many times I had planned what I should do if the factory should be discovered on fire, but I had never thought of a fire starting in the warehouse, for no fire was ever kept there – not even a lantern had been there for weeks. The building was all alone except for the piles of dry pine and basswood lumber between it and the factory.

About this time I began to hear the hoarse cry of fire from neighbor to neighbor. The first thing to be done was to give notice to the fire company. Too much depended on every moment of time to trust to anyone and I started on a run for the engine house, but just as I passed the factory my brother-in-law shot past me on one of his horses yelling worse than a Comanche Indian. I did not know before that any horse could go so fast nor that human lungs could utter such unearthly shrieks.

The boys who slept in the factory were now awake and yelling after the example set them by my brother-in-law. I told one of them to stay about the factory and then we went down to see what could be done for the warehouse. By the time it got there, it was pretty near all burned. Not only the million sections stored there, but all my tools and agricultural implements and ever so many other things that represented the hard work of years, were destroyed. Worse than all, a south wind drove the fire fiercely into the lumber piles and it seemed for a time that nothing could prevent it from sweeping clear to the factory and licking that up, too. How I prayed to hear the roar of the fire engine. Finally it commenced coming and hundreds of willing hands lifted the great hose toward the lumber piles. Almost immediately the water stopped, however, for in their zeal they had pulled the hose in two before it was fairly coupled together. A messenger had to be sent back to the engine to stop the flow of water, while the hose was mended. Finally it began pouring a great muddy stream on the burning piles, but to my great dismay the fire seemed to burn just as well with water on it, as it did without. Water was poured through the openings between the boards, but as soon as it stopped even for an instant, out came the flames again.

The fire was within a few feet of the second warehouse containing seasoned lumber and hives, and it seemed as though even a fire engine was powerless to stop it. By this time men and women had formed lines, standing in the mud meanwhile and pails were passed from one to the other, while this second warehouse was kept drenched on the roof and along the sides and ends by means of little pumps. For hours the people fought, making apparently but little headway. But the wind finally veered around a little and a snow storm set in, and by God’s providence we conquered.

In the weeks just past my health had been threatening many times to break down and so as soon as the fire was under control, I began to feel that if I were to be of any use that next day I must get some sleep. Many friends assured me that this was a wise thing to do and therefore, I obeyed and went to bed. Now it has always been said of me that one reason why I can stand so much mental strain, is that I can go to sleep at any time of day or night. Was I equal to the task now? I began to feel that I was not, until I questioned myself in regard to God’s promises. Whose property was it that was burning? I held the title to it and it was all paid for, but was it mine or the Master’s? I had often told him on bended knees to take me and all that I was and all that I had, in his care and keep it.

Here was a chance to practice what I had preached. If it was through any fault of mine that the building was burning I might lie awake, and worry, or get up and right the fault. If, however, it was something I had nothing to do with, why should I be troubled? If the property was all in God’s hands and he had seen fit to let it be taken away in this manner, why should I worry or lie awake when rest was so much needed? This reasoning took perhaps five minutes and then I went to sleep as if nothing had happened. When the fire engine stopped for a few minutes, however, I sprang up instantly. My wife asked what the matter was. I told her that they had stopped throwing water. Can you imagine how sweet the sound came as the booming commenced once more. I afterwards learned that they had stopped long enough to disconnect the hose and put it under the railroad tracks, so it would not be cut by an approaching train. One other stop was made and I awoke as promptly and commenced dressing, until they got started again. Even while sleeping soundly I kept in mind that if our town waterworks should give out, the fire would again be upon us.

When daylight came the flames still burned high, but they were held captive. Sure enough the firemen had exhausted the water from the reservoir and they were obliged to wait until afternoon, so that more could be pumped, and then and not until then, was the fire put clear out.

My loss amounted to some ten or twelve thousand dollars, and I had insurance for a little less than five thousand. I had a great abundance of seasoned basswood and pine that the fire did not touch, and better machinery than I ever had before, so I knew we should not be behind very much on filling orders. The day after the fire I read from the book of Nehemiah how they built up the walls when the gates had been burned down by the enemy.

By March 16 we had quite a pile of selections ahead awaiting orders, and by working from daylight until dark we managed to supply the wants of our customers as if nothing of the kind had occurred.

Now, then, how did the building get on fire? Nobody knows. My wife inquired about our old trusty family horse who for toward twenty years had been a faithful servant. He used to bring my wife to church from her home down by the river, and later he had taken each new baby out for its first ride allowing it to hold the lines. We showed her a blackened horseshoe. It was all we could bring as a remembrance of the faithful old friend that had been her special property for so many years.

The first neighbor who came on the ground when the building was burning saw the doors of the warehouse open and the two horses loose in the field. Poor old Jack, in his fright, ran back into the fire and turned into his old accustomed stall. Both horses had very strong leather halters on their heads, and the rings in the halters were found in the ashes by the mangers, indicating without question that somebody had unbuckled the halters and slipped them off, turning the horses loose, after they had removed the bars and opened the doors. The warehouse had been fired in different places. “An enemy hath done this,” was the language of everyone, but what enemy had I who could thus desire to destroy my property, taking the lives of domestic animals and endangering the whole of this part of town?