By: A.I. Root

In the year 1866 I had a light colony, or rather nucleus that I put into the cellar. This cellar was so arranged as to keep an even temperature of about 40°. We gave only one comb of sealed honey early in December, at which time the bees were almost entirely destitute. Nearly everyday I tapped on the side of the hive, expecting the bees to be out of honey long before spring but, to my surprise, they answered promptly every time until the middle of March, when I set them out of the cellar. I was agreeably surprised to find not more than 20 dead bees on the bottom-board, though other colonies had lost two or three quarts and on taking out the frame of honey supplied, I found what I would have supposed an impossibility – nearly all of it remained. These bees must have lived more than three months on less than three pounds of honey. By placing my ear against the hive in the cellar I could hear scarcely a sound unless the hive had been jarred in some way.

What I Learned About Wintering

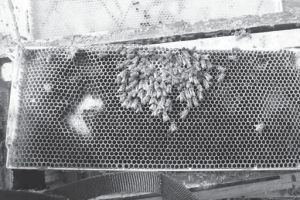

By 1874 I had learned that, if a 10-frame colony in the fall had seven combs of brood and bees enough to cover them nicely, it would not be too strong the first day of September. If the brood-combs all bulged above the brood with sealed stores and the other combs were full and heavy with pollen and sealed store, there would be an ample supply. Uncapped, watery-looking honey I did not consider desirable. I favored sugar syrup in place of honey, fed to the bees principally during the month of August. During this month I also fed enough to keep up brood-rearing briskly, moving the combs about but little and leaving each colony all the pollen gathered and just in the position the bees placed it.

Wintering Bees on Candy

I once tried some home-made candy for wintering bees. I put it over the cluster, but it soon got soft and sticky and finally ran down on the bees and daubed them up in such a way that I never wanted to see any more candy and I suppose the bees felt about the same.

In October, 1875, I was away from home for a couple of weeks and when I returned my feeding was rather behind. It was about the middle of October and I was so afraid that the bees would not get the syrup nicely sealed that I stopped feeding and sent a barrel of “Coffee A” sugar to the confectioners to have it made it into nice hard candy. I proposed to give several good strong colonies about half their rations in candy laid under the quilt on top of the frames.

All unoccupied combs were removed and piled up where they would be handy the next Spring. I was rather disappointed to find that my strong colonies when thus condensed did not cover more than four to seven combs, yet when these were well filled with stores I thought the supply ample. If I had any doubt I laid sticks of candy on top of the frames under the quilt. The sticks were 10” by ½” by ½”. I gave one colony nothing but empty combs and candy. The candy was very hard and brittle and therefore I did not think it unwholesome. It cost about 12¢ a pound.

Preparing Bees for Winter

By November 1, 1875, I had reduced my bees from 108 to 90 colonies and I believed they were all supplied with Winter stores. But after weighting them I was much disappointed in finding that I dared risk very few of them, especially since they were so much stronger than usual. There was no help for it and since I dared not feed syrup so late, I gave them bricks of candy. There is one very great advantage in favor of the candy: it can be given at any time and under any circumstances without the least danger of robbing.

I untied 18 colonies by simply lifting bees, combs and all into the hive desired, and did not see a single queen attacked. I was agreeably surprised to find that where the hives were no further apart than six feet from the center to center, any one could be united with its neighbor and the hive itself removed at once when the bees were flying, for they would all find the hive to which the colony had been united by hearing their comrades call, so that not a single bee would return to the old stand and be lost.

Where the distance was greater than six feet I shook all the bees off the combs in a heap before the entrance, removing the old hive entirely. The bees on the wing gathered at once at the hive where the commotion was, attracted by the loud humming of their companions and all went in like a new swarm.

My colonies were not all in the condition I could wish, after all. Those in the house apiary had too few bees, all being new colonies made late in the season. The others had plenty of bees, but on this very account were found short of stores in October and that is the reason I gave the candy. The bees stored this in the combs at a very fair rate during warm weather, but when it became cool the candy was taken very slowly. Since they could not finish it entirely, I put them away, candy and all.

Importance of Housing Bees Early

I feel sure that dampness in some form or other had much to do with my losses in wintering in the early years and by the Fall of 1875 I was advising that all colonies be fixed, whatever the plan might be, during dry weather. So far as I can recall, my losses occurred when I had housed the bees during cold wet weather. Indeed, in the Fall of 1873 they were housed during a snow storm. I had waited so long that I dared not wait any longer, so in they went. Perhaps the manure heaped around the hives that I was trying at the time contributed to keep the hives damp during the entire Spring also. In the Fall of 1874 I put the bees in the bee-house on the 3rd of November, at least two weeks earlier then ever before. They were put in as dry as a chip, for it was during very dry weather when it was so warm that I feared the consequences; yet they seemed to go into that desirable dormant state at once. As I was all taken up with the glass house, the majority of the colonies were almost entirely neglected (?) until March 15th: and yet, strange to say, they seemed almost precisely as they were the day they were put away, and they made as fine progress as one could wish until the freeze during the April following.

A strong colony of bees will dry out a damp hive or a set of damp moldy combs. In fact, one might drench the bees with water and they would soon be all right again if they were given only half a chance. The small colony, on the other hand, can do nothing and will remain damp and cold until they perish. If a colony has a cluster only on one side on combs containing watery honey or combs that look blue and moldy, it is pretty safe to assume that the bees will not Winter well and that the sugar that was fed, the time, the bees, and the queen will all be lost. The remedy is to unite colonies until they are strong the moth millers, ants and all insect enemies enough to be able to drive out not only mites, but also dampness and the wintering malady as well.

Wintering on Candy and Flour

In 1877 I made some experiments in giving bees small amounts of candy and discovered that under this treatment the combs soon filled up and everything began to prosper. I began wondering if there were not some way o giving them a big lot at one time. Candy bricks could be put above the frames, but after these had been consumed the bees were quite apt to build combs above the frames. Putting a heavy frame of sealed honey into a hive seemed the most satisfactory way and therefore I had a cake of candy made that would just fit inside a Langstroth frame. The bees at once filled their combs as if it were clover time and yet it was done so quietly that not a robber even smelled any feeding going on. One such frame weighted seven pounds and I felt that a pair of them would Winter a large colony even without a drop of stores. Then it could be packed as snugly as desired under chaff cushions. After the candy was all gone the bees could build comb in the frame that contained it.

In 1877 I made some experiments in giving bees small amounts of candy and discovered that under this treatment the combs soon filled up and everything began to prosper. I began wondering if there were not some way o giving them a big lot at one time. Candy bricks could be put above the frames, but after these had been consumed the bees were quite apt to build combs above the frames. Putting a heavy frame of sealed honey into a hive seemed the most satisfactory way and therefore I had a cake of candy made that would just fit inside a Langstroth frame. The bees at once filled their combs as if it were clover time and yet it was done so quietly that not a robber even smelled any feeding going on. One such frame weighted seven pounds and I felt that a pair of them would Winter a large colony even without a drop of stores. Then it could be packed as snugly as desired under chaff cushions. After the candy was all gone the bees could build comb in the frame that contained it.

While feeding this candy many eggs were laid, but as the bees were entirely out of pollen no larvae made their appearance. So I had some more slabs of candy made the same as before, but with one part of flour to ten of sugar. This looked all right, so I made another one one-fourth flour. The bees ate this in preference to the pure sugar and soon had a nice lot of brood.

Wool Cushions for Winter

I often thought of hair, fur, feathers, etc, for cushions and did experiment in the Winter of 1876 with a colony done up in wool; but the bees got tangled in it in such a way that I desisted. A friend of mine used cushions made of wool, I believe, with good results, although they were rather more expensive than chaff or cotton. I decided that the covering for all these kind of cushions would have to be made of duck, for any other fabric would soon be gnawed through. Many of my friends wasted money in trying different kinds of woolen cloth, but everything I tried like this was sooner or later eaten full of holes and spoiled by the bees, except hard twisted cotton such as I have mentioned.

In 1876-77 I wintered less than a quart of bees in the house apiary and had the little colony increasing almost all winter long by help of the chaff cushions.

Frames on End in Winter

In the February number, 1883, a correspondent suggested standing the regular Langstroth frames on end to two hive bodies, so as to have room for packing material. This was an old idea even at the time, first mentioned I believe by Mr. Quinby, also described in Gleanings in the early days. I do not know that I ever had a report from anyone who had tried the plan, however. I suggested the use of only three combs a little farther apart than in the Summer. These would easily hold all the bees needed for Winter, but of course for an extremely large colony six combs would be used instead of three.

Overwintering In A Bee House

My first building for bees was a Winter repository that I built in the Fall of 1869. The walls were packed with sawdust and there was a complete ventilating scheme to provide fresh air.

I had a stone foundation laid, 10×14 feet with two rows of brick on top, with holes in opposite sides of the wall, made by omitting two bricks, to allow ventilation. Sawdust was packed under the floor and in the walls. The walls were made of 10- inch studding, to permit 10 inches of sawdust packing. We put a double window in one end and a double door in the other. The ventilator through the roof was seven inches in diameter and extended just below the ceiling inside. The lower ventilator through the floor was simply a square box seven inches across and covered with wire-cloth to exclude mice. A very small stove was ample to keep the room comfortable.

Bees Hum When Too Cold

As early as November of that year I moved in one rather weak colony to test the house. One quite cold night outdoors before I moved them in, the bees were making a very loud humming, such as weak colonies always make when they are very cold. In two hours after carrying them in they were so still that not a sound was noticeable unless that hive was disturbed.

Many had said that five inches of sawdust would be plenty, but in a building in which no help is expected from the sun I thought we should find fully as much trouble in keeping off the effects of the sun as in guarding against frost; and even though the room were kept as dark as midnight, I did not expect the bees to be as quiet as they should be unless the temperature were never higher than 40 or 45°. Whenever we were not able to maintain such a temperature, I expected to set the bees outdoors.

By the 20th of November I had put my 46 colonies inside the bee-house. On account of the bad weather I am sure that it would have been better if I had put them in about a month earlier. The day we put them in happened to be quite cold and as I did not want the caps on I took them off and left them on the Summer stands. Most of the colonies behaved quite well, although the hybrids made up their minds that they would stay where they were. They had been extremely cross all the season and positively objected to any assistance whatsoever. From one of them I removed the cover, thinking that the freezing air would drive the bees down among the combs; but after leaving them thus until all the rest had been taken in I decided they would have to be treated like refractory children and put in by main strength.

Hybrid Bees Refuse to Become Quiet

I am not in the habit of being intimidated by bees; but the battle array on top of the frames was rather fierce looking and when I approached, the bees came more than half way to meet me in an onslaught much like that of a young hailstorm. Smoke was of no use, as they seemed to be all out of the hive before I got within 10 feet; yet I tried it and think that for almost the only time the fumes of tobacco seemed to have no terrors for the bees. I might smoke them until they lay on their backs, but the moment I stopped blowing they pitched in with fresh vigor until I finally, when I lost all patience and carried the hive in, letting the bees come along or stay behind, as they liked, I had about the fairest exhibition of real hybrid bee fury that perhaps had even been displayed. They buried themselves in my shoes, trousers, coat, vest, hair, collar, waistband and everywhere else. None of them got lost as they were so busily engaged in bestowing their whole attention on my precious self. Thus we all got into the bee-house, but instead of taking their places orderly in a row, as I had planned they should and very particularly desired that they should just then, they pitched in more furiously than ever until I began to think I would rather take a back seat and be a spectator a while.

I am not in the habit of being intimidated by bees; but the battle array on top of the frames was rather fierce looking and when I approached, the bees came more than half way to meet me in an onslaught much like that of a young hailstorm. Smoke was of no use, as they seemed to be all out of the hive before I got within 10 feet; yet I tried it and think that for almost the only time the fumes of tobacco seemed to have no terrors for the bees. I might smoke them until they lay on their backs, but the moment I stopped blowing they pitched in with fresh vigor until I finally, when I lost all patience and carried the hive in, letting the bees come along or stay behind, as they liked, I had about the fairest exhibition of real hybrid bee fury that perhaps had even been displayed. They buried themselves in my shoes, trousers, coat, vest, hair, collar, waistband and everywhere else. None of them got lost as they were so busily engaged in bestowing their whole attention on my precious self. Thus we all got into the bee-house, but instead of taking their places orderly in a row, as I had planned they should and very particularly desired that they should just then, they pitched in more furiously than ever until I began to think I would rather take a back seat and be a spectator a while.

Well, these bees raised such a howling that I really began to fear that the bee-house was going to enjoy anything but quietness and the other colonies as well seemed to be rapidly getting demoralized. I left the door open on cold nights until the thermometer went down almost to freezing, still the bees persisted in promenading constantly on the tops of the frames, scolding away worse than a lot of sitting hens.

Elisha Gallup, I noticed was advising more ventilation for bees in Winter. As I had covers off of the worst colonies and the entrances all open, I did not know any better way to ventilate unless I put the hives in the middle of a 10-acre lot with the bars down.

Finally my business became so pressing at the approach of the holidays that I had no time to see to the bees. After they had been neglected about a week I was surprised to find them quite orderly, although the cross rascals did boil over the top as soon as I showed my face. I then went away and shut them up in total darkness. After this I slipped in quietly about once a week and for the next four weeks the thermometer did not vary one degree from 40°, although the weather outside was cold and warm alternately. One it was so warm for several days that I could hardly understand how it could be so much colder inside. I do not think the sun produced any effect at all upon the interior. The bees in most of the hives behaved just as Mr. Gallup had described in his writings. Were it not for their bright color and their moving when touched I might have thought them dead.

The 46 colonies of bees all wintered safely in the bee-house. On March 10th we put them on their summer stands, nearly as heavy as when they were put in. Some tried to persuade me that they would be better if left in a little longer, but I thought they were better out of doors if properly protected and cared for.

Reviving a Starving Colony

We came very near having 45 colonies instead of 46, for after removing them from the bee-house on march 10th, we had some of the coldest weather of the whole Winter – two degrees below zero. It was with a feeling of nervousness that I went around and gently tapped on each hive. Those that I feared most I tried first, of course; but when they all answered promptly “All right,” I began to breathe freely. However my hopes went down to zero and no mistake, on finding that one of the heavy hives, when rapped repeatedly, gave no response. It was indeed too true. I grasped the hive and rushed madly for the kitchen stove. With breathless sorrow I hung over that little domicile which only the night before was the happy home of peace and plenty, but where all was now still. No little yellow bodies moved so softly and quietly about, but all was cold and frostily in death.

On one side of the hive there was plenty of sealed honey, but the bees had eaten along the other side where the relentless zero weather found them consuming the last on that side. I warmed them and re-warmed them, but not a movement until, after an hour or two, a few stirred a little, but that was all. I began to think I would have to give up, as I had tried the same thing the year before. My presence, too, was beginning to interfere with the preparations of the noonday meal. However, I could not give up yet. I visited the hive again, but this time with less determination than before and slowly walked toward the bee-house. I built a fire in the little stove, I opened the hive, brushed the bees into a large pan (all I could get out of the cells) and warmed and warmed them. It was no use – only a feeble movement occasionally. At length the sun came out through the frozen air into the single bee-house window. I put the pan on the window-sill to help in looking for the queen I had not yet found. Was it my imagination or was the sun really reviving them? Yes, they were certainly coming to. After sprinkling them with honey and water they got brisk space and on standing a comb up in the pan they crawled on it as fast as they revived and those in the cells towards the sun began to wriggle out. Before night I had the whole colony back in their hive; and a month later the pretty yellow queen was enlarging the circle of worker brood with all the matronly pride imaginable. So you see I came out ahead in the race of life and death and had the whole 46 colonies all right.

On one side of the hive there was plenty of sealed honey, but the bees had eaten along the other side where the relentless zero weather found them consuming the last on that side. I warmed them and re-warmed them, but not a movement until, after an hour or two, a few stirred a little, but that was all. I began to think I would have to give up, as I had tried the same thing the year before. My presence, too, was beginning to interfere with the preparations of the noonday meal. However, I could not give up yet. I visited the hive again, but this time with less determination than before and slowly walked toward the bee-house. I built a fire in the little stove, I opened the hive, brushed the bees into a large pan (all I could get out of the cells) and warmed and warmed them. It was no use – only a feeble movement occasionally. At length the sun came out through the frozen air into the single bee-house window. I put the pan on the window-sill to help in looking for the queen I had not yet found. Was it my imagination or was the sun really reviving them? Yes, they were certainly coming to. After sprinkling them with honey and water they got brisk space and on standing a comb up in the pan they crawled on it as fast as they revived and those in the cells towards the sun began to wriggle out. Before night I had the whole colony back in their hive; and a month later the pretty yellow queen was enlarging the circle of worker brood with all the matronly pride imaginable. So you see I came out ahead in the race of life and death and had the whole 46 colonies all right.

The ‘House’ Apiary

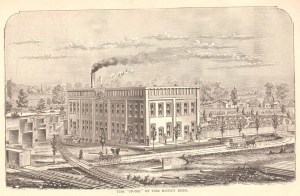

In the Summer of 1875 I became interested in a new project and for fear it might be only another “glass house” experiment I issued a supplement to Gleanings, feeling that the pages of the regular number should be occupied only with matter of known value.

Extracting honey is a laborious operation and a great portion of the labor involved is the necessity of carrying the combs from the hive to the extractor and back again. In order to have my 48 colonies located within a couple of yards of the extractor I determined on a double-walled, sawdust-packed, eight-sided building with three colonies to a side and with entrances through the double wall by means of a two-inch tube. This would provide space for 24 colonies with entrances about two feet apart. Four feet above the floor I provided another tier of hives, thus making the 48 colonies in all. I proposed making the three hives all in one with only thin boards to divide the three colonies and as all would be well protected from the weather a thin cloth covering would be ample protection. I planned to have the whole inside of the room warm in winter by retaining the animal heat from so many colonies closely packed.

When time to extract my plan was simply to take out the combs and hand them to an assistant at the extractor after the bees were brushed back into the hive. Any bees taking wing would soon fly out of the two large doors, one on each side.

By June 28, 1875, I had my unfortunate glass house all removed and in its place the octagon house. It was a two story building that was originally made to grind grain with a windmill for motive power.

By July 14th my “house apiary” was nearly ready for the bees. I decided to put but 36 hives in the room. As explained, there were eight sides, each six feet wide and seven feet high. The east and west sides were occupied by large double doors and the others contained six hives each, three on the floor and three on a 20-inch shelf three feet from the floor.

By July 28th 15 colonies had been placed in the house apiary and more were being put in as fast as a queen was found emerged. The first two queens (which had emerged on the 20th) were laying by the 28th and although I took no pains at all to make the entrances unlike either by paint or otherwise, there was no confusion. I took particular pains to see a queen take her flight. When she came back while she took a look into the entrances on either side, she seemed to say, “That is not my house, nor that one, but this one is,” and then she glided into her own two-inch auger hole.

The walls were four inches thick and I worried a little about the bees having to crawl the distance, but I found they swept right in and alighted with their huge loads of pollen directly on the outside combs, the combs running parallel with the side of the building. I was astonished to find that bees were much quieter in a darkened room. When the doors were closed the room was as dark as ink.

When shaking the bees from the combs they generally crawled back into their own hive at once, but I had a few heavy colonies that started in a body and marched all over the walls and ceiling. However, if no other hive was open they almost immediately went back again when the room was darkened.

Notwithstanding the apparent success of the house apiary, I advised no one to invest in a similar building until I had had an opportunity of trying it at least a year, for there was a chance that it might turn out like the glass house and I had forgotten the money that that cost.

The First Winter in the House Apiary

In December the mice got into the house apiary and I at once proceeded to make some mouse-guards out of pieces of galvanized sheet iron 2¼” square, large enough to cover the 2” auger hole entrances to the hives. In the sheet iron I punched two 5/16” holes so close together that they cut each other, making an opening large enough for one bee. A galvanized tack held these mouse-guards in place.

In the old bee-house the bees were in the habit of getting out of their hives on a very warm day; but those wintered in the house apiary, having entrances to the outside, seemed perfectly contented so far as I could see. After two weeks’ time there were a few dead bees brought out of the house apiary, perhaps a dozen per colony on the average, but these undoubtedly died of old age and were not an abnormal number of that length of time.

On February 12, 1876, bees were working on meal out of doors. I think it was the first time I ever fed meal in February. The sun shone very hot on the covers of the hives.

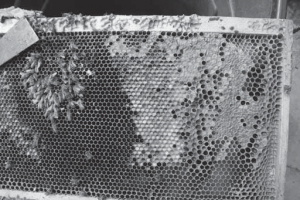

One colony I found dead in the house apiary. The bees died of starvation, although there were combs containing several pounds each at the other side of the hive. It was quite a good sized colony, but the bees were clustered on new combs and the hive stood right close to the door, which did not fit very tight. If the heavy combs had been placed next to the cluster or if the space had been contracted so that it would just hold the bees, no doubt I would not have lost the colony.

Trouble with the House Apiary

In the Spring of 1876 I noticed the fashion young bees had of pouring out of the top of the hive when it was open for examination. This did no harm, except that when one was through working there was a shower of bees determined to return to their own hive and to the very spot they came from. Even after they were all driven away they would sometimes hang about the door for an hour or two and it is doubtful whether they all regained their own hives if the entrances happened to be at a distance from the doorway. In case of hives out of doors it makes no difference where they get out, they always find their own entrance.

In the Spring of 1876 I noticed the fashion young bees had of pouring out of the top of the hive when it was open for examination. This did no harm, except that when one was through working there was a shower of bees determined to return to their own hive and to the very spot they came from. Even after they were all driven away they would sometimes hang about the door for an hour or two and it is doubtful whether they all regained their own hives if the entrances happened to be at a distance from the doorway. In case of hives out of doors it makes no difference where they get out, they always find their own entrance.

By May, 1876, seven colonies had died in the house apiary, five on the north and two on the south side. None of these colonies were very strong in bees except those that starved. In the house apiary it seemed such an easy matter to feed candy or sugar at any time that I was careless about the amount of stores, thinking that I could give more at any time in a few minutes.

When the house apiary was first built it was a novelty and it was a pleasure to have everything nice and exact. After a while it got to be something of an “old story” and then in stepped a besetting sin – a disposition to prefer working at some new thing. I was beginning to feel that I would like very well to try something else, but I realized that if I was really unable to stick to what I then had on hand and do that well, I should deserve to lose the confidence and patronage of my friends and readers.

There were a good many bees on the floor of the house apiary and to hear them snapping under my feet was enough to make me nervous, when I had been trying so hard to keep the floor clean. To be sure, the bees had no kind of business on the floor any way, but that Spring they had taken the peculiar fancy of crowding out under the edges of the cloth coverings of the hives rather than going out by the entrance.

Although I had put sealed honey close to the cluster in every colony running short of stores in April, I discovered that of the 36 hives only eighteen contained live bees. Many of the colonies had starved with sealed honey plainly visible through the glass division-board and a few had really used particle in the hive and then lay dead in great heaps that seemed to say to me “Why did you, with so much care and pains, bring us into existence only to let us die in such a shameful way just as the gentle April breezes were beginning to call us forth to activity?” The colonies had perhaps reared more brood than those out of doors, as there were great heaps of dead bees where there was but a small colony last fall. Those out of doors did not starve because they did not rear brood and exhaust their stores.

On May 9th the bees in the house apiary were dwindling so rapidly that I feared none would be left. Most of the colonies outside were building up, but a few of the weakest were going down with the well-known Spring dwindling.

By May 18th conditions were much improved again. My whole apiary by dwindling had been reduced to 52 colonies and then the weather changed and colonies with only a half-teacupful of bees began to build up. The house apiary, too, caught inspiration caused by how honey, plenty of new pollen and the soft balmy air, until bee culture seemed the very easiest thing in the world.

By May 18th conditions were much improved again. My whole apiary by dwindling had been reduced to 52 colonies and then the weather changed and colonies with only a half-teacupful of bees began to build up. The house apiary, too, caught inspiration caused by how honey, plenty of new pollen and the soft balmy air, until bee culture seemed the very easiest thing in the world.