Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

For the Eager Honey Producer –

The Classic System of Two-Queen Colony Honey Production

An old technique for the modern mega-management beekeeper

By: James E. Tew

Beekeeping then and now

Happily, beekeeping has kept up with many modern-day advances, but that evolving characteristic means that beekeeping today is not the same as beekeeping was many decades ago. Advances in protective equipment, improvements in honey processing equipment, introduction of new pest complexes and large migratory operations are only a few of the myriad of changes that have been occurring in our beekeeping industry.

I surmise that one of the biggest changes is that modern beekeeping is now primarily known for pollination while honey production is now the second factor for which beekeeping is known. That is exactly opposite of what beekeeping priorities were thirty or so years ago.

In the golden years of beekeeping past, honey production was the Number 1 goal of dedicated beekeepers. Nectar flows determined the beekeeper’s management schedule and then, when possible, supplemental pollination services were sometimes provided. In many instances, neither the grower nor the beekeeper felt that it was financially feasible to use added honey bee populations. That concept has radically changed. Priorities have evolved.

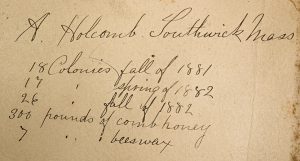

Figure 1. A post card from Amasa Holcomb, Southwick, MA, that was sent to Dr. C.C. Miller in 1883. Note that 300 pounds of comb honey were produced in 1882. There was no mention of extracted honey.

As a young beekeeper all those years ago, I was familiar with the beekeeping priorities of the day. Yes, even then, liquid honey ruled, but even that emphasis was a change from what honey production was decades before my time. I roughly estimate that eighty to one hundred years ago, comb honey was preferred to liquid honey because it could not be adulterated with sugar syrup. Comb honey was “pure.” Books were written about comb honey production. Talks were presented at meetings. Techniques abounded.

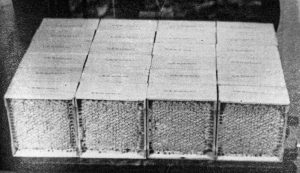

While comb honey is still produced in newly developed plastic containers, the old tried and true way of producing honey in basswood section boxes has seemingly died a long, slow death. Basswood boxes for comb honey production are only available from a few remaining vendors – if you can find them at all. The loss is not horrendous, but it is significant.

Figure 2. Basswood section boxes of comb honey. C. Killion photo, 1951.

It always bothered me that perfectly good nectar sources – basswood trees – had to be harvested to produce the unique wood that would bend into a box shape. But in obvious ways, moving from basswood boxes to plastic containers has only brought us different challenges. I suppose that could be a discussion for another time, but not today.

My belabored point is that beekeepers once produced comb honey in basswood boxes and now we don’t. That technology is gone. That’s a big change that took decades to develop.

An aside…

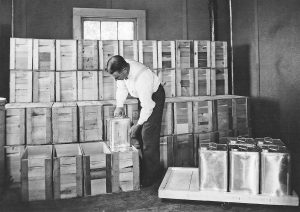

In this vein of bee things that are gone, a rarely lamented change is the move from 60# metal tins to common white plastic buckets. The tins could be tightly stacked on a truck while round buckets do not stack tightly. But current plastic buckets have more comfortable handles than the small metal handles on honey tins. But you should know that the change was rapid. It seems to me that in just three to four years, metal tins were dropped from catalogs to be replaced by plastic buckets. Now, I can’t even find a photo of a honey tin on the web. Things change. They always do.

Figure 3. Double crates of honey tins. Each crate weighed 125 pounds.

The classic double-queen system of honey production

Everything I have written in this article, has been to get to this point. Why write about a dated technique that few modern beekeepers still use? It was the rage then but as with basswood comb honey boxes and metal honey tins, things change. But if you have the energy and the interest, this is a technique you can still use in your bee operation.

When I began beekeeping, one of the advanced concepts was to use two queens to build up an abnormally large population of worker bees just in time for the nectar flow. Just as the flow started, the colony, that had two queens, whose brood nest was separated by a double screen or a modified inner cover, produced a double bee population. Excessive honey crops were the desired results.

A disclaimer…

I have not tried to manage bees in two-queen colonies in about thirty-five years. Readers, due to my current energy and strength capabilities, I doubt that I will ever try again. Never in my entire beekeeping career have I been an accomplished two-queen beekeeper, but all the advanced beekeepers were giving it a try. Talks were presented at meetings. Success stories were staggering. You had to be there. At this moment, I do not know a single two-queen beekeeper. But in its day, this management scheme was widely touted.

To put this article together for you, I relied heavily on the pamphlet published by C.L. Farrar in August, 1958 (Farrar, C.L. Two-Queen Colony Management for Production of Honey. ARS-33-48. Available in archival form at: https://archive.org/details/twoqueencolonyma48farr/page/4/mode/2up).

Quoting Farrar from his work,

“Two-queen colony management represents an intensive system of honey production designed to obtain the maximum yield from each hive. During any short honey flow (about two weeks) one large colony will produce more honey than two or more smaller colonies having the same aggregate number of bees. In single-queen colonies the production per unit number of bees increases as the number in the colony increases up the maximum (60,000 bees). This efficiency relationship remains high when populations are further increased through the use of a second queen. Because small colonies increase in population with time, their production efficiency over long honey-flow periods will rise. However, colonies with large populations throughout either long or short flow produce the greatest amount of honey, because their efficiency is high over the entire honey-flow period.”

To emphasize his point, a large population of bees will produce more honey than the same population housed in two or more hives. Getting an abnormally large bee population – before the flow started – was the reason for using a second queen.

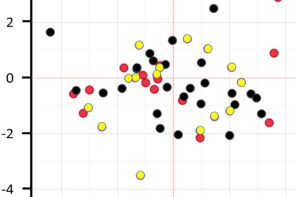

Figure 4. An old photo comparing two-queen colonies with standard colonies. The small colonies were in bright sunlight while the tall colonies were deeply shaded. My photo editing skills were stressed.

Everything about the double queen system was big. Big bee populations, big (tall) colonies, big honey and pollen crops, and big management inputs. The results were to be big honey crops with powerful colonies passing into the following Winter. A five-hundred-pound crop (yes, 500 pounds) was not considered impossible when using this technique. A fully functional double-queen colony could have the amazing population of twenty-five to thirty pounds of bees in it.

It’s all in the management details

Pollen reserves

In 1958, our industry had not yet developed artificial pollen products. At that time, to produce large bee populations, a beekeeper would need extensive pollen sources. Obviously, your colonies cannot produce brood without pollen. That same pollen reserve later became important to wintering colonies. The desire was to produce large colonies going into Winter to have strong colonies for the two-queen system during the next season.

Queens

For this system, queens need to be purchased and be readily available. In 1958, they were and the cost was not as great as today. You should be wondering if allowing the split part of the colony to produce its own queen was an option. The is answer is, “not really.” While it clearly could be done, valuable seasonal time would be lost while the bees were growing queens and not growing a worker bee population. It would seem to me that modern two-queen beekeepers would be confronted by queen availability during the early season of the year.

Hive equipment

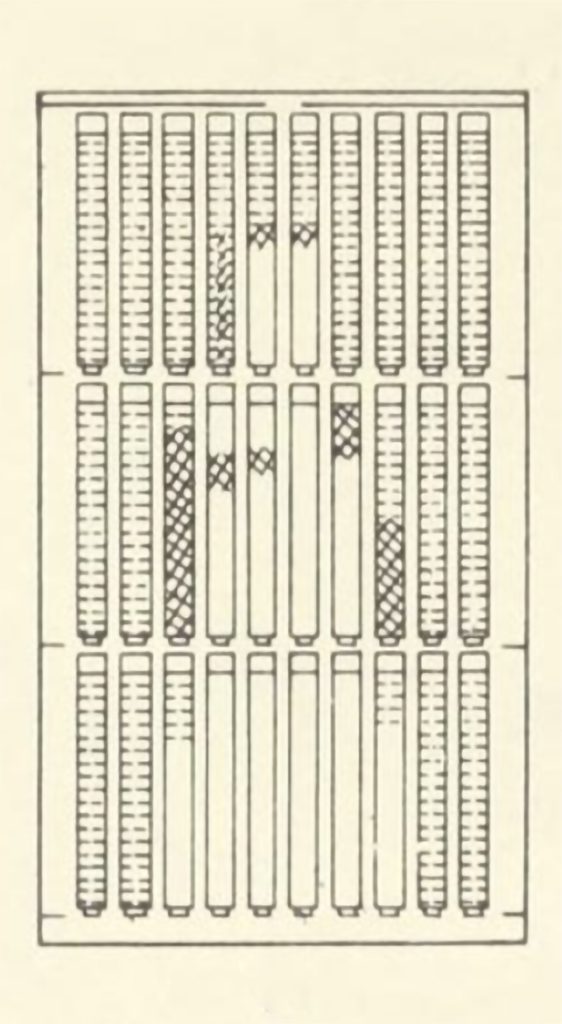

Two queens with a double worker population naturally results in a tall hive. Due to that fact, the two-queen colony would need to sit on a firm foundation that was essentially on the ground. Hives that were seven deep boxes tall were not uncommon. Hive stands would not be used.

To forestall bees storing honey in the valuable brood nest area, supers were never allowed to be more than half full. As boxes were filled, they were removed and processed and then the wet equipment was returned to the tall hive.

Other than purchase costs and assembly labor, shallower equipment was not held in disfavor. The reduced weight of full supers was the obvious reason. But a lesser-known reason was that some researchers felt that bees wintered better in shallow boxes. It was felt that bees’ wintering cluster had more interactive space to share Winter food stores in the spaces between the boxes. In fact, Dr. Farrar wrote, “The size and shape of the hive units have little effect on production if enough (boxes) are used for brood rearing, food reserves, and the storage of surplus honey.” That is an interesting observation that goes beyond this honey production discussion.

Farrar added the comment that the most efficient management was possible when all brood boxes were uniform and therefore interchangeable. The same would be (mostly) true for super sizes.

Shallower supers were preferred to deeper supers. Apparently, bees fill and cap the shallower equipment faster than deeper equipment. Again, weight would be another prime reason for using shallow equipment.

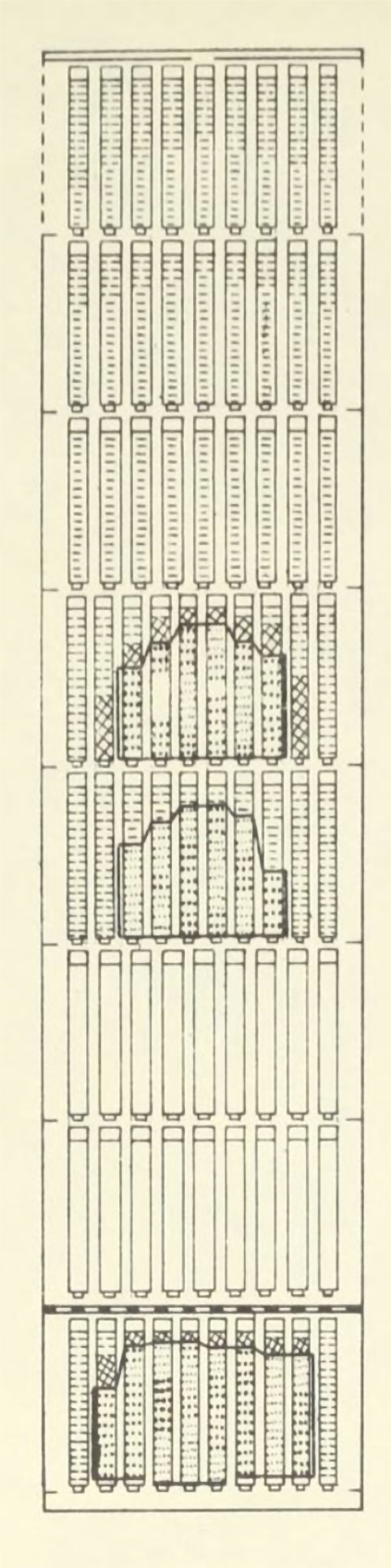

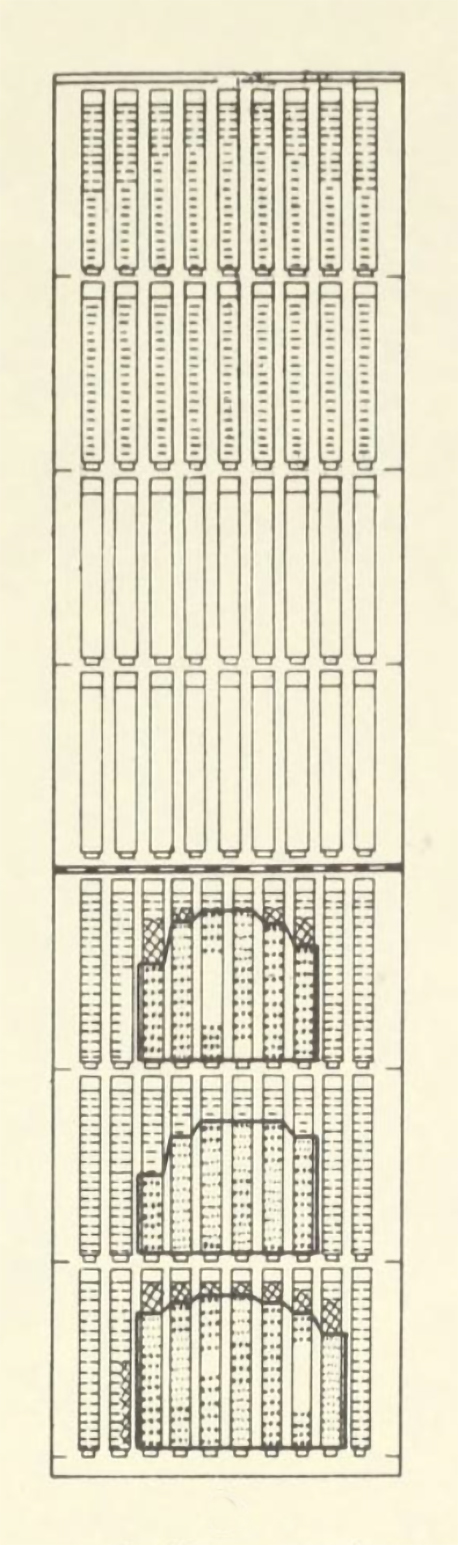

Figure 5. The position of the two brood nests in a full functional two-queen system.

Figure 6. Late season two-queen system with brood nests combined and excluders removed.

Management points

To produce stronger colonies, you need to begin with strong colonies headed by young queens. Weak colonies had no place in the two-queen system. Make everything large. Beginning five to seven weeks before the flow, begin the two-queen development process. Two weeks later, make a strong divide from the original colony and either use a double screen or a screened inner cover to separate the split from the parent colony. In his paper, Farrar provides intricate details for quantities of brood and bees that will need to be moved to different locations with the developing mega-hive.

After the new queen was installed and was producing copious amounts of brood in the split above the screen inner cover (usually ten to fourteen days), the screened inner cover was removed. The colonies were kept separated by queen excluders.

Empty brood nest space was provided above the lowermost colony. A queen excluder was used above the bottom colony. This was a necessity. At this point, the beekeeper had a strong queen in the lower unit with an empty box of drawn comb (preferred to foundation) atop of the lower unit. The extra space allowed for continued brood production.

Above the lower queen excluder was the recently introduced queen with a second brood nest with a similar configuration of brood and empty brood nest space. Then yet another queen excluder was put above the second top colony between the top brood nest and the supers. The dual queen excluders confine the queens to their respective spaces and became an aid to keeping up with the two queens when the colony was opened to remove full supers and for inspection.

Most of the surplus honey storage occurred above the second colony in the top of the tall colony. Again, it is important to write that the supers were inspected and additional space was added when supers were only 50% full. The intent was to discourage the bees from storing honey in either brood nest area.

Swarming and supersedure were not thought to be any more relevant than swarming and supersedure in single-queen colonies. If swarming was becoming an issue in a two-queen unit, the recommendation to use the “shook swarm” technique to attempt to get things back into order. That sounds like a management headache.

Not a technique for colony increase

As I began to write this piece for you, I envisioned the two-queen system having the possibility of ending the season with two colonies. While I feel that could still be accomplished, Dr. Farrar discouraged using this two-queen system as a technique for making colony increase.

Indeed, as the season ended, he suggested just removing the excluders and allowing the bees to select the better queen. Presently, the current cost of queens would be a hinderance to that recommendation. Having a $40 queen only produce for a single season feels extravagant. However, outside of the two-queen system, this general setup could be used to assist a “weaker” colony in becoming stronger but is a totally different discussion.

Figure 7. Former two-queen system

prepped for Winter.

The reason for this recommendation of not using the double-queen system for colony number increase was presented in his summary included in his paper. “The larger pollen reserves accumulated after the colonies have been reduced to a single queen status make it possible to overwinter stronger colonies for the next season.”

Times have changed. I extensively discussed that. Does the development of modern pollen supplements obviate some of the old two-queen management recommendations?

This is not for the faint-hearted

After my experience all those years ago and after reviewing my sources for this article, I can clearly write that this is not a management scheme for all beekeepers. Only those beekeepers with the time and the penchant for intensive colony management should take it on. The payoff is great, but so is the labor and monetary input.

Then why bring it up?

Like so many other things and recommendations within beekeeping, managing bees for a double queen scheme is an idea dating back to the 1930s. Does it still work? It certainly worked at one time, but I can’t speak for the present.

In the 1950s, herbicides were nonexistent. Queens were available and were not as costly. Honey was the Queen of Beekeeping. But we now have ready access to pollen substitutes and other improvements. So, I bring this subject up for those rarefied few of us who want to push the beekeeping envelope. That will not be me doing the pushing. If you try this technique, I would like to know how it works out.

For more information and instruction, in addition to the reference already provided, I refer you to the sources that I have provided below.

Current information on the two-queen system is included in:

The Hive and the Honey Bee. 2015. Pp 505-507.

ABC & XYZ of Beekeeping. 2020. Pp 679-680

As always, thank you.

If you are still reading, you are one tough beekeeper. A sincere thank you for your beekeeping dedication. I have not been able to do any more than introduce you to this old, advanced concept. I know you will have questions. I certainly do.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

tewbee2@gmail.com

Co-Host, Honey Bee

Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com