By: Ross Conrad

You can eat the larvae.

Given current projections, by the year 2050 there will be approximately nine billion people living on Earth. Estimates are that our food production will need to almost double from what it was in 2005 in order to feed everyone. (Alexandratos 2012, Tilman 2011) Despite the “feed the world” promises of today’s modern industrial agriculture and techniques that seek to harness Genetically Modified Organisms, pesticides, GPS technology and expensive machinery for food production, there are still nearly 1 billion chronically hungry people worldwide.

An inefficient system

Our current agricultural system is woefully inefficient burning many more calories of energy than each food energy calorie produced. For example, consider the energy consumption of a hypothetical purchase of a fresh-cut non-organic salad mix by a consumer living on the East Coast of the United States. A lot of gasoline, diesel and electricity are used during the tilling, planting, fertilizing, application of pesticides, irrigation, harvesting, transporting, processing, packaging, refrigerated transport, and refrigerated storage. And that is just to get the product into the grocery store refrigerated display.

To purchase this salad mix, a consumer likely travels by car or public transportation to a nearby grocery store. At home, the consumer refrigerates the salad mix for a time before eating it. Subsequently, dishes and utensils used to eat the salad may be placed in a dishwasher for cleaning and reuse – adding to the electricity use of the consumer’s household. Leftover salad may be partly ground in a garbage disposal and washed away to a wastewater treatment facility, or disposed, collected and hauled to a landfill. Although not comprehensive, this packaged salad mix example illustrates an accounting of the energy use related to producing, distributing, consuming, and disposing of this product. While organic, biodynamic and permaculture agricultural practices all help to reduce the total amount of energy used to produce our food, how it is produced is not the only thing we have to change. In order to meet our future nutritional challenges, what we eat, and how it is packaged, transported, stored and consumed must all be reevaluated.

One possible alternative

One area that appears ripe for more research and expansion in order to improve the energy efficiency of our food supply is insects. According to taxonomist Yde Jongema at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands, there are over 2,000 edible insects in the world. While edible insects have traditionally been a large part of human diets, in some societies such as ours, there is a degree of distaste for their consumption. While uncommon in Western countries, some African and Asian countries have a long history of eating honey bee larvae and is it often revered as a special delicacy.

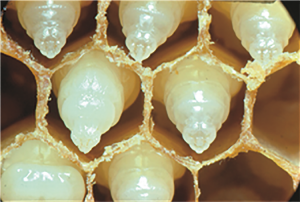

Drone development time from egg to harvestable larvae is eight to nine days. While honey bee brood can be harvested from colonies at different stages in the development from larvae to adult, to maximize biomass of the harvested brood it is best not to harvest before the larvae stop feeding, which is at the time of capping. Honey bee larvae at this stage will have increased in weight almost 1000 times and protein content will have increased almost as much. This growth rate is much faster than the growth rate of more traditional protein sources such as cattle or chicken. As pupae grow older, there will be an increasing amount of chitin produced for the developing cuticle making the brood less palatable. The cuticle is fully developed just before emergence when the brood resembles an adult and imparts an unpleasant taste (Schmidt & Buchmann, 1992).

While freezing is the most common method of preserve larvae and pupae, smoking and drying are sometimes used. Brood can reportedly be frozen for up to 10 months without adverse effects. In China and Japan, drone larvae are canned for export and even though there is not a large demand in European and American markets, canned bee larvae and pupae, sometimes coated with chocolate, may be found in some specialty ethnic food stores.

The traditional aversion to insect foods in Western civilization appears to be based on custom and prejudice rather than any established health or safety concerns. Despite this, it has been estimated that the average American eats about two pounds of dead insects and insect parts a year that end up in vegetables, rice, beer, pasta, spinach and broccoli. For example the hops used to brew beer, can contain large numbers of aphids. Even the U.S. Food and Drug Administration guidelines for the allowable “levels of natural or unavoidable defects in foods that present no health hazard for humans” includes insects. Moreover, companies like Pepsi have experimented with using cricket and mealworm powders in its products. (Garfield, 2017)

Honey bee larvae have traditionally been eaten fresh and raw right out of the hive along with the honey and pollen in the combs. These days however, some Asian countries will prepare honey bee pupae (in the white or pink eye stage) for human consumption by boiling or pickling. While both open and capped brood will stay alive at room temperature for a few hours, fresh larvae and pupae should be refrigerated as soon as possible and freezing, drying, boiling, roasting, baking or frying should take place within 24 hours after collection to avoid spoilage since insect proteins decay much faster than beef, chicken, lamb or pork.

A Nutritional Powerhouse.

Research into the nutritional value of honey bee brood indicates that it is high in carbohydrates and protein, contains all the essential amino acids. Brood is a good source of phosphorus, magnesium, potassium and the trace minerals iron, zinc, copper, selenium and most of the B-vitamins, as well as vitamin C and choline. The fat content provides a balanced composition of saturated and mono-unsaturated fatty acids with only about 2.0% being polyunsaturated fatty acids. (Abd Al-Fattah 2016, Ghosh 2016, Finke 2007, Crane 1999)

Eaten fresh and raw, honey bee larvae are sweet and fatty tasting. When not frozen, honey bee brood is quite fragile, and can rupture easily, especially if it has been frozen previously. This softness, however, is also part of their gastronomic potential, and if preserved well bee brood can bring a surprising and unique element to a dish. While raw larvae at room temperature are soft and plump, in the mouth they can be popped with slight pressure from the tongue, releasing a mouth-coating liquid within. Raw pupae at room temperature are slightly firmer as a result of their later developmental stage and so resist pressure a little more than the larvae, though they contain a similarly viscous interior. When cooked or dried they tend to retain their shape and are pleasantly crunchy with a rich nutty flavor.

As more and more beekeepers utilize the culling of capped drone brood as as part of a natural Varroa control strategy, drone larvae and pupae has the potential to become a commodity. However production of bee brood is highly reliant upon adequate food availability within colonies and brood production becomes problematic during periods of prolonged dearth such as during a drought for example.

Nordic Food Lab

The consumption of insects in the Western World is perhaps most prevalent in the Scandinavian countries. This is partly due to members of the Department of Food Science at the University of Copenhagen who have developed the Nordic Food Lab as “a non-profit, open-source organization that investigates food diversity and deliciousness.” In 2013, the Lab launched its Insect Project to fully explore why, unlike most of the developing world; the Western World doesn’t eat insects. This effort has been condensed into the first book to holistically explain entomophagy, the human use of insects as food, titled: On Eating Insects: Essays, Stories and Recipes. However, the Nordic Food Lab is most commonly known for its sister institution Noma, Copenhagen’s world-famous restaurant run by Chef René Redzepi where insects are a regular part of the fine dining experience.

An Entrepreneurial Frontier

While American restaurants have been slow to embrace edible insects, one new entomophagy business that is looking to change this situation is called Laroua and is based in Vermont. The founders of the business are two recent University of Vermont graduates, Kitty Foster, who graduated with a degree in Nutrition and Food Science, and Julia (Jules) Lees, who took a Food Anthropology class while getting her degree in Anthropology. As Jules explains it, it was their common background in sustainable agriculture that led the duo to start the business. “. . . What has really been good about this business for us is that it is at the nexus of our mutual interests in food systems, nutrition, and environmentalism. It’s an opportunity to encourage beekeepers to organically control their Varroa mites while at the same time creating an additional food stream from something that would otherwise be a waste product. And it’s good for you! It feels like it takes all of our interests and brings them into one.”

Laroua is seeking to establish a market for bee larvae that is supported by top chefs who are advocates for sustainable, nutrient-dense food sources. At the same time they will create an additional revenue source for Vermont beekeepers who manage their hives organically and through restaurant promotions, conscious diners provide the beekeeper with recognition for their efforts. From Jules and Kitty’s perspective, drone brood removal as part of a Varroa control program adds to the branding of drone brood as human food, potentially helping to sustain the beekeeping industry by providing a new source of revenues for beekeepers.

The company currently pays beekeepers $5 a pound for drone brood in the comb. “I think a lot of people don’t do anything to control their Varroa mites so I feel like there’s a huge niche for us to come in and say, ‘you need to control your mites, your bees are dying because of the mites and, we’ll pay you to do it,’” says Jules. Laroua’s company slogan is “Save the bees. Eat them.”

Recipes

For the adventurous, here is a basic recipe for:

Garlic Butter fried Bees (adapted from FAO 1996)

- ¼ cup butter

- 6 cloves garlic

- 1 cup cleaned honey bee larvae/pupae

Directions: Heat the butter over low heat in a frying pan or pot. Slowly fry the garlic so that in about five minutes it is slightly brown. Add the bee larvae and continue frying at the same temperature for another five to 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. Do not overheat or the garlic will burn.

Meanwhile Daniella Martin, author of Edible: An Adventure Into the World of Eating Insects and the Last Great Hope to Save the Planet, and host of the website Girl Meets Bug, the insect cooking/travel show, posts the following on her website:

“Bee larvae, when sauteed with a little butter and a few drops of honey, taste very much like bacon.

“Sometimes, when I talk about eating bees, I hear concern about the problems plaguing bee populations. Naturally, I would never recommend a bug-gredient that is threatened.

“I primarily eat drone larvae, which I get from from beekeepers whom I’ve bee-friended.

“…Many beekeepers have a special comb just for drones, which they sometimes use as bait for potential parastites.

“Periodically, they remove this comb altogether, toss it into the freezer to kill any ‘extras’ like mites, and then either throw it away or feed it to chickens, if they have any. If more people knew how delicious they are, I think the chickens might have to peck elsewhere!”

According to author Daniella Martin, when cooked just right, drone brood tastes like bacon. This is the inspiration for the BEE-L-T sandwich.

Bee-L-T Sandwich

Ingredients:

- Bee larvae

- 1 egg white

- 1 tsp butter

- 1/4 tsp honey

- 1 tomato

- 1 leaf lettuce

- 2 slices of bread

- 1 tbsp mayonnaise

- 1 pinch salt

Sautee the bee larvae in the butter, with a tiny bit of salt and a few drops of honey. Once larvae become golden brown and crispy-looking, remove, and mix into enough egg white to cover and bind them into a mass. Then return them to the sautee butter, pressing them together into a patty.

Toast bread, and slice tomato. Spread mayonnaise on toasted bread when ready. When bee patty becomes firm, place it atop the lettuce and tomato on the sandwich. Enjoy!

…And for those of you who may be hesitant to eat your beloved honey bees, perhaps this recipe I came across for one of the honey bee’s major pests, the Greater Wax Moth, will be more to your liking.

Popmoth (adapted from FAO 1996)

Heat some coconut oil and drop fresh (live) or frozen wax moth larvae into the hot oil. Their skin will break and the proteins will expand, making them look like popcorn. Remove them before they become too dark, let the oil drip off them and salt or flavor them to taste similar to popcorn or potato chips. Consider drizzling them with honey for a sweet treat.

Bon Apetite!

References:

Abd Al-Fattah M A, Sanaa A Mahfouz and Enas O Nour El-Deen (2016) Nutritive composition analysis of honeybee Apis mellifera L. brood as edible insect: Chemical composition and amino acids content, Journal of Sports Medicine and Doping Studies. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0673.C1.009

Alexandratos, N., and Bruinsma, J., (2012) World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision No. 12-03 (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation)

Crane, Eva (1999) The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting, Routledge, New York, pg. 551

Finke, Mark D., (2007) Nutrient Composition of Bee Brood and its Potential as Human Food, Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 44:4, 257-270, DOI: 10.1080/03670240500187278

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, Value Added Products From Beekeeping, FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 124, pp. 257 and 261

Garfield, Leanna (2017) PepsiCo has experimented with mealworm powder for its snacks and drinks, Business Insider, Accessed April 8, 2018 at www.businessinsider.com/pepsico-alternative-protein-mealworm-powder-2017-5

Ghosh, S., Jung, C., Meyer-Rochow, V.B. (2016) Nutritional value and chemical composition of larvae, pupae, and adults of worker honey bee, Apis mellifera ligustica as a sustainable food source, Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology: 19(2) 487-495

Jensen, A.B., Evans, J., Jonas-Levi, A., Benjamin, O., Martinez, I., Dahle, B., Roos, N., Lecocq, A., Foley, K (2016) Standard Methods for Apis mellifera brood as human food, Journal of Apicultural Research, DOI: 10.1080/00218839.2016.1226606

Schmidt, J.O. & Buchmann, S.L. (1992) Other products of the hive. J. M. Graham (Editor), The hive and the honey bee (pp. 927–988). Hamilton, IL: Dadant & Sons.

Tilman D, Balzer C, Hill J and Befort, B L (2011) Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 108 20260–4

Ross Conrad is the author of Natural Beekeeping: Revised and Expanded Edition.