By: Meghan Milbrath

Our goal as beekeepers is to keep our bees safe and healthy, and to make sure that our beekeeping doesn’t affect the health of the humans and the environment around us. If we don’t monitor, we risk spreading disease to neighboring honey bee colonies or even native bees, or we risk overusing chemical inputs.

The fight against Varroa is a battle on two fronts – we are combating the mites within our hives, while at the same time we are struggling to breed bees that can survive this pest. This two-front problem has led to a divide in the beekeeping community – fighters on one line or the other sometimes don’t see eye-to-eye. One side values the quest for better bees in the future, and they don’t see how we can get there when we treat all the time. The other side values the health of our current animals, and they don’t see how we can beat a disease when crashing colonies are adding to the risk.

These values can seem at odds when we approach the issue from one side or the other, and it sometimes feels like we will lose both battles while continuing to fight among ourselves. Don’t despair! We have a knight in shining armor – the one weapon that can save us on both fronts, and restore peace to the beekeeping world – Monitoring! I understand that monitoring may not sound like the sexiest solution to a deadly global problem, but it is truly the one tool that we have that helps us keep our own bees alive, reduce the spread of disease, and work towards getting better bees.

Hands on training is the best way to learn monitoring. Take a friend to the beeyard with you. photo by Andrew Potter.

A decade ago, before we really understood the value of monitoring, we had two bad options for the varroa problem: don’t treat, and hope that some bees survive with valuable traits, or treat all the time and hope that there is an outside solution to this pest. Now that we have monitoring, both of these extreme positions are outdated (Those of you still fighting about this on the internet, you are out of touch – it is time to put down those pitchforks and pick up a monitoring kit!). It is no longer acceptable to let colonies die when we can identify the survivors before colony death – the deaths resulting from the ‘live and let die’ strategy are unnecessary and promote the epidemic. It is also not necessary to simply use chemical treatments all the time, which can lead to health risks and possible resistance. Monitoring allows us to breed better bees by identifying survivor colonies, and it allows us to protect our individual colonies by identifying when treatment is needed. With monitoring, we can value the health of our bees now and the health of bees in the future.

Monitoring allows us to practice integrated pest management (IPM). IPM is a system of managing pests that was designed to reduce harm to humans and the environment. A good IPM strategy is based on the following principles:

Understand the biology and life cycle of your target pest,

Monitor to make sure that the pest doesn’t reach damaging thresholds,

Use a variety of non-chemical tools first (biological, cultural, physical),

Use chemical tools when the pest will cause damage.

Obviously, we can use monitoring for IPM step 2, making sure that the Varroa mites haven’t reached dangerous levels. However, we can also use monitoring for step one, understanding the life cycle of this pest. When we monitor year after year (and take good notes), we can start to understand the natural Varroa dynamics in our area. For example, in Southern Michigan, where I live, I have seen the same cycle over the last few years – I don’t see any mites in June, just a few in July, and they start to peak in mid-August. I know that I have to practice some sort of control before mid-August in order to keep by bees from this dangerous peak. This can change of course, but I have a good understanding of the Varroa population dynamics in my area, which can drive my management plan, and help me develop a strategy where the mites never reach dangerous levels.

Even if you have never monitored, you likely have some data on mite population dynamics in your area – if you lose over 30% of your colonies every year, you likely are having a dangerous peak in parasite load when your Winter bees are getting made. You have enough data to tell you that you will need to take action earlier in the season to protect your bees.

How to monitor

If we want to use monitoring for step 2 of IPM (making sure that mites don’t reach damaging thresholds), we need to use a type of monitoring that provides us with a number we can match against a threshold. For Varroa, the number we want is the proportion of mites per bees, or percent infestation. This means that we need a known number of bees, and we need to see how many mites we have. We can do this with a version of the sugar roll/alcohol wash/ether roll. Other methods may allow us to see mites, but they don’t provide us with a clear, actionable number. For example, if we just uncap drone brood and don’t see mites, we don’t know we are safe. Likewise, it is really difficult to interpret the numbers we get off a sticky board, because it depends so much on the size of the cluster. We want a result that can be compared from hive to hive, within a hive over time, and against a known threshold.

To get a result in terms of percent infestation, take ½ cup of adult worker bees (about 300) from a frame in the brood nest, and add them to a jar with a screened top. You will use powdered sugar or alcohol (or another substance – sometimes people use windshield wiper fluid or ether) to knock the mites off. The mites are shaken through the screen into a container where they can be counted. If you divide the number of mites by three (to account for the 300 bees in the sample), you will get percent infestation. For step by step instructions, and instructional videos, and info on pre-made kits visit www.keepbeesalive.org. The substance that you use to remove mites will determine how many you recover from your sample. Usually, you can get the most mites off when you use an alcohol wash. The downside to an alcohol wash is that it also kills the sample of bees (still way better than losing your whole colony, but it is hard for those of us with big soft hearts). You can use a sugar roll or CO2 to knock mites off if you can’t handle the alcohol wash, but just keep in mind that you will likely get fewer mites (you can underestimate). Usually, this underestimation isn’t enough to change what you need to do for management, but it is important to take into account.

Here’s the trick. Once the bees are washed and mites counted wash them again. More mites? No mites? Both results tell you something. The first, you didn’t shake the sample long enough and/or hard enough. Learn from that.

The second – you probably did. Every time. Every. Double test to make sure YOU are not the problem.

How many mites are too many mites?

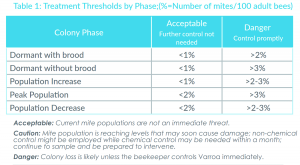

The Honey Bee Health Coalition has a good table of treatment thresholds in their “Tools for Varroa Management Guide” available at https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/varroa/.

In the table, you’ll note that the safe threshold varies over time, depending on the brood in your hive.

Table 1: Treatment thresholds recommended by the Honey Bee Health Coalition, where % = number of mites/100 adult bees. Acceptable = current mite populations are not an immediate threat. Danger = Colony loss is likely unless the beekeeper controls Varroa immediately.

Table 1: Treatment thresholds recommended by the Honey Bee Health Coalition, where % = number of mites/100 adult bees. Acceptable = current mite populations are not an immediate threat. Danger = Colony loss is likely unless the beekeeper controls Varroa immediately.

This table is a good place to start, but keep in mind that your risk can change from year to year, and you may have to adjust. Make sure to always check the published dates when you look at threshold recommendations. Varroa-virus dynamics have changed in the U.S., and older numbers are no longer safe or relevant. If you use threshold recommendations from even five years ago, you will be in trouble.

When to monitor

It is good practice to start monitoring early in the season, even though varroa risk is usually low at this time. First, it will give you the full picture of Varroa growth and dynamics – you will be able to follow the population over time, and get an understanding of the risk in your area. Secondly, starting early will give you good practice, so that when risk is high, you can trust your data. There is a bit of a learning curve with monitoring – especially with making sure that you get a full scoop of bees. You want to be good at monitoring before the risk gets high, so that if you see a low number,

you know your bees are safe (and you aren’t worried that it is because you messed up). A standard recommendation by extension is to monitor once a month through the season, and a little more when risk is high. For example, in my area I would monitor in May, June, July, beginning of August, mid-August, beginning of September, mid-September, and beginning of October.

There are tools that can help you monitor. You can make the kits yourself out of cheap and easy materials (Sugar roll kit instructions: https://beeinformed.org/2013/03/19/how-to-make-a-sugar-roll-jar/, or an alcohol wash kit instructions: http://scientificbeekeeping.com/an-improved-but-not-yet-perfect-varroa-mite-washer/). However, there are a lot of us who sometimes mix up “can” with “will.” We all can go out and buy hardware cloth and cut it, but will we? Sometimes it is easier to purchase kits, and you can find them for sugar rolls or alcohol washes.

There is even a phone app ‘MiteCheck’ (for android and Ios) that will walk you through each step to make sure you don’t forget anything when you are in the field. The MiteCheck program also has a citizen science program, where you can report your mite numbers – helping scientists understand dynamics across the country. You can view current mite counts by county to know when levels are becoming high in your area. Find out more at www.mitecheck.com.

Pitfalls

Don’t fall prey to some of the common monitoring and management mistakes. The biggest mistake that beekeepers make is they are too late. Remember, you want to keep your bees safe. This means that you want to prevent a parasite boom from happening – not just revenge kill the mites after your bees are damaged. Too many beekeepers wait to monitor/manage mites until it is too late, and the bees are already damaged. Make sure you have treatments on hand (or are able to order them immediately), if you know you’ll need them. Also make sure to account for the time they take to work – some of treatments need to be in the hive for weeks. You don’t want to wait until your colony is totally overwhelmed, take a week to go to the bee supply store, and then apply a treatment that takes four weeks to work. Be proactive, and focus on protecting your bees.

Another common mistake is to assume that once you have treated your bees will be fine. You want to monitor after treatment to ensure that it worked well. You can use a sticky board during treatment to witness mite drop, and you should do a regular check (alcohol wash) after the treatment time has concluded to make sure treatment was sufficient, and that your bees are still safe. It is unfortunately all too common that beekeepers treat in the late Summer, only to have their hives bombarded by the hives crashing around them, and a colony that has low numbers can spike later on. Watch for a resurgence – it is very common in many areas.

Finally, make sure that your information is up to date. Years ago, it was just recommended to treat in the Fall. We now know that fall treatment is too late, and if you aren’t watching your local mite populations, you may be coming in after the population spike. There is also bad messaging about first year beekeepers – there is a bad rumor on the internet that first year beekeepers don’t need to worry. That may have been true in the 1990s, but it hasn’t been the case for years. Finally, make sure that you are getting up to date threshold information. Old threshold numbers still abound on the internet, some of them 10 times higher than what we consider safe now!

Using monitoring to protect your bees and to move towards better bees

The near-term goal with mite management is to never let our colonies become overwhelmed with parasites. The health of our colonies depends on having enough healthy individual bees. If too many bees have injury or viruses from mites feeding on them, the whole colony will suffer and die. With monitoring, we can understand when peaks are likely in our area, and also to know right away if we have any colonies that are in trouble, so we can help them immediately and prevent disease from getting worse and from spreading.

Our long term goal with Varroa is to find bees that can survive this pest. Before we had monitoring, the only way to know which colonies could survive a Varroa epidemic was to see which ones didn’t die. This resulted in lots of unnecessary death, suffering, economic loss, and it contributed to the spread of disease. While I think it is essential that we find bees that than find a balance with Varroa, I am happy that I don’t have to treat my animals so horribly anymore to do so. When we monitor, we can tell which bees can’t handle Varroa before they die. If I find a colony where the Varroa population is unmanaged by the bees, I step in and treat that colony to save the workers, and will requeen with a queen from a better hive or from a breeding program to manage Varroa. I can get the information that I need earlier in the season, and save all of my colonies. That way I’m helping to find Varroa-resistant bees, but I’m doing so in a responsible way.

Good monitoring practice is the key to colony health, and to developing better bees.

Monitoring can help us get out of the quagmire of perpetual death and disease, and save us from our own poor practices. We’re really struggling to get control of the varroa-virus complex, and we continue to make a lot of mistakes.

We lose a lot of colonies every year because we didn’t realize they were in danger.

Many bees die because the disease isn’t managed in time- we treat too late because we don’t know our local disease dynamics.

We have perpetuated the epidemic, making the risk worse for our neighbors, and putting native bee populations at risk.

We are dependent on chemical treatments in our colonies.

We are really mean to each other when we talk about Varroa management.

Get a kit, and go out and monitor. Take good notes, so you know what your disease risk in your area. Make a plan to control mites before they endanger your bees, using your previous years’ data. Monitor through the whole season to make sure you immediately can respond to peaks. Use monitoring to identify the colonies that can handle mites, and use queens from those colonies to requeen your other hives. It is on all of us to keep our bees healthy and get this epidemic under control.