By: Daivd MacFawn

When examining a hive, the beekeeper can tell what is going on inside by answering a few important questions. Does the colony have swarm, supersedure, or emergency queen cells? Are there empty queen cells from which a virgin queen has emerged? How many queen cells total are there, and where are they located? The beekeeper also looks to see if there are worker brood, drone brood, and the stages of this brood (egg, larvae, pupa, emerged). Are there signs of a laying worker(s) such as drone brood raised in worker cells? How large is the brood nest? Where are the frames of pollen located, and where are the brood nest pollen bands? Is honey stored in the corners of frames of the brood nest or in the super above the brood nest? Are there signs of wax moths or small hive beetles such as debris on the bottom board? How much damage exists from wax moths or small hive beetles? Are there signs of American Foulbrood, European Foulbrood, or of Varroa mites (“snott” brood, Varroa visible on drone brood, deformed wings)?

A normal colony

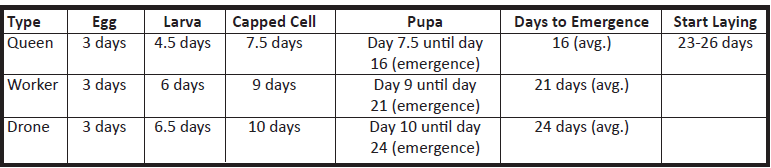

The brood development of a normal colony follows the seasonal bee-year. The colony begins building its population the latter part of December, with peak brood-rearing culminating during the nectar flow. When swarming occurs, it is usually during the nectar flow and in healthy colonies that have plenty of honey and pollen available. In the spring, worker brood follows the 1/2/4 rule that means there should be twice as many larvae as eggs, and four times as many capped cells/pupae as eggs.

Queens

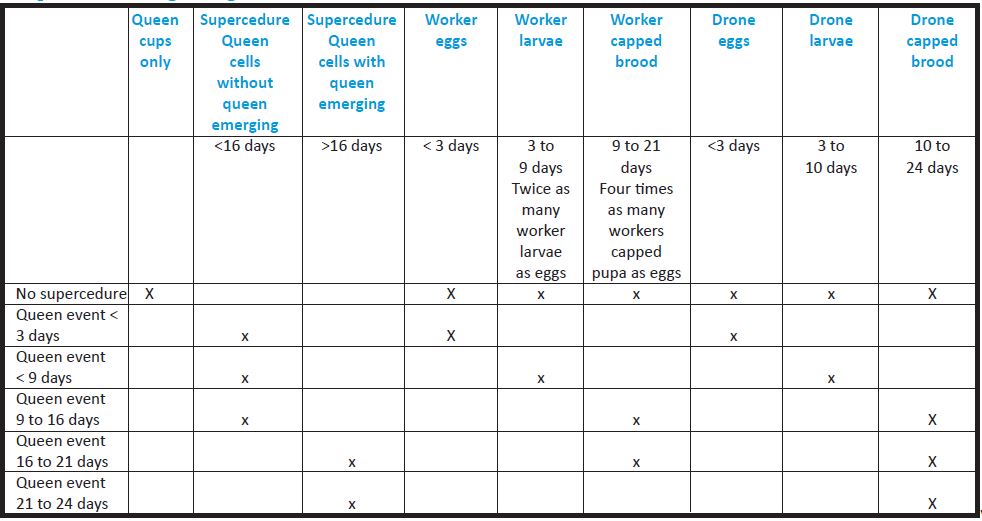

When examining a colony for queen issues, look for queen cells and other queen-related conditions. If the queen cells are toward the frame bottoms and numerous (greater than five or six), you probably have swarm cells. If the queen cells are toward the frame center and top and are less numerous (two or three), you probably have supercedure cells. If the queen cell is drawn from a worker cell and elongated, you probably have an emergency queen cell. Look to see if the bottom of the queen cell has been chewed open (raggedy edges). If so, a queen has emerged from the cell, and the workers have not yet torn the cell down.

Figure 1. Broad

Development Times

Figure 2 Swarm Cells/cups on the Frame Bottom with Two

Emergency Cells Midway up the Frame (Kathy Carpineto) Note the pollen between the Queen Cells and the Honey in the Upper left of the Frame.

Figure 4.

Healthy brood.

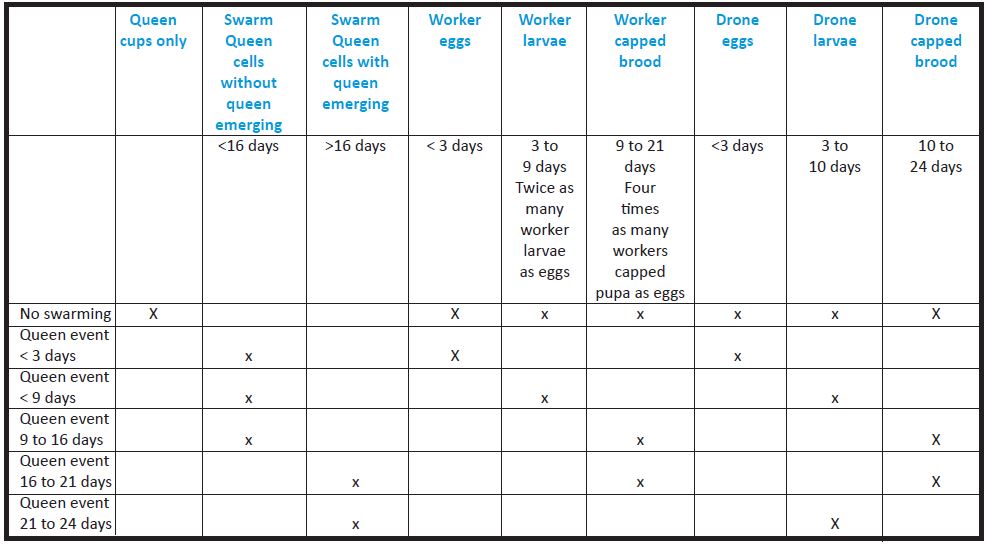

Other queen-related conditions also should be assessed. Look for worker brood (eggs, larvae, or capped) in the frames. If you have eggs or larvae, and the queen has not emerged from the queen cell, you know the colony recently swarmed, probably less than 16 days ago. If there are only capped worker brood, which is capped after approximately nine days, you know the colony probably swarmed nine to 21 days ago. If you have a queen cell from which the queen has emerged, together with capped worker and drone brood, you know the colony probably swarmed 16 to 21 days ago. If you have an empty queen cell, and have no capped worker brood but do have capped drone brood perhaps with some drones emerging, you know the colony probably swarmed 21 to 24 days ago, and you probably have a new queen that is getting ready to lay. After emerging, a new queen typically takes seven to 10 days to mate and start laying. Often, after swarming has occurred, the colony will backfill the brood nest with nectar/honey until the newly mated queen begins to lay.

Swarming: Diagnosing Queen Issues

Figure 5. Swarming: Diagnosing Queen Issues David MacFawn

Figure 6. Supercedure: Diagnosing Queen Issues David MacFawn

Laying workers

A laying-worker bee develops when the colony’s queen dies for some reason, and the colony is not successful in replacing her. This failure to replace the queen may be due to the colony having only larvae that are more than three days old when the queen dies, or the queen not returning from her mating flight. Sometimes a worker will start to lay, but her eggs are not fertilized. These eggs are known as drone eggs. The eggs are infertile since the worker has not mated with a drone and has no semen. This is the last effort for the colony to propagate the species. As brood pheromones that suppress workers from laying eggs diminish, a worker may start to lay. Laying workers usually take several weeks to develop after loss of a queen.

All workers are females with ovaries and the other egg-laying organs, but these organs are undeveloped due to suppression by the queen’s pheromones. When the queen disappears and is not replaced, her pheromones also disappear and with them, suppression of the worker’s ovary and egg development. As a result, a laying worker is created. The colony is still trying to pass on its genetics, but it can only do so if the laying workers produces drones that mate with a virgin queen from another colony in the Drone Congregation Area (DCA).

Figure 7 A frame of laying worker drone cells. (Photo courtesy:

Mark Sweatman)

Figure 8 Close-up of laying worker drone cells. (Photo courtesy:

Mark Sweatman)

The laying worker’s abdomen is typically not long enough to reach the cell’s bottom, so the eggs are laid on the cell sides , Multiple eggs are laid on each side of the cells. The bees enlarge the cells from worker cells to drone-size cells. Usually, worker drones are smaller than queen-laid drones. Laying workers lay more drones than a queen does, and the drones result in multiple combs/frames becoming all drone cells, effectively ruining the combs/frames for later use in producing worker bees.

Brood Nest

The pollen and honey define the brood nest boundaries, thereby defining the colony size. As a beekeeper, you should assess the brood nest by asking the following questions: Where are the outer frames of pollen and honey located in the brood nest? Where is the band of pollen above the brood nest? Where is the honey above the pollen band? Is this band of pollen in the bottom brood chamber or the super above? Is there a lack of pollen and honey in the frames? If there is a lack of pollen and honey, you may need to feed the colony.

Upon examination of the worker brood, larvae should be floating in food. If not, the colony has a nutrition issue. There is not enough honey and pollen for the nurse bees to produce the larvae food. The colony probably needs feeding.

Signs of wax moths and small hive beetles

Is there debris on the bottom boards of a hive? Are there other signs of wax moths or of small hive beetles (SHB) inside the hive? How much damage already exists from wax moths or SHB? Such conditions may suggest a hive in trouble. If you see wax moths and cocoons when removing the hive cover(s), look further down into the equipment stack to determine if you have a weak hive. Wax moths and wax moth cocoons are usually a sign that the colony is weak. The colony is not strong enough to manage the amount of space in the hive. If you have a weak colony, you need to determine if you should re-queen the colony, combine the colony with a stronger colony, or dispose of the colony. The extent of wax moth damage to the combs will assist you in making this decision.

Figure 9 Super with Advanced Wax Moths: Woodford, South

Carolina. David MacFawn

Figure 10 Frame with Advanced Wax Moth Damage. Woodford,

South Carolina. Taken by David MacFawn

Wax moths are attracted to the dark comb where brood has been raised. Hence, the challenge is to maintain your honey supers on the hive such that the queen does not lay brood in them. Wax moth eggs will not hatch at 64°F and are completely dormant below 41°F. This temperature sensitivity means that you should not have an issue with wax moths when outside temperatures fall below 64°F. You will have issues with SHB if you feed pollen patties in large quantities early. I found it best to control SHB by placing the patty directly above the brood nest in small quantities and feeding patties more often. Also, keeping the colonies in direct sunlight helps. SHB are usually not a large issue in January/February. You can use non-scented “Swiffer” pads to help control SHB during warm months. Very few honey bees get stuck in the pad.

Figure 11. SHB damaging comb. (Photo courtesy

Steve Seigler.)

Signs of American or European Foulbrood

A healthy bee has plenty of hair or/setae all over its body. Healthy brood looks “normal,” without sunken or perforated caps (American Foulbrood) or dark-colored larvae before capping (European Foulbrood). Healthy brood is not hardened like chalk (Chalk Brood). There should be no signs of exterior Varroa mites, and no deformed or distended wings (Varroa or viruses). If there are many dead bees (greater than 100) in front of the colony, and they look “greasy,” it may be due to pesticide poisoning. American Foulbrood (AFB) is caused by a spore-forming bacterium that will persist for decades. The infected worker pupa has sunken and perforated caps. When a small twig is inserted into the diseased cell, the infected pupa will “rope out” two to three inches. European Foulbrood (EFB) usually occurs in the larvae stage. EFB is considered a stress disease that is caused by a non-spore-forming bacterium and usually clears up with a nectar flow. Adding a frame of nurse bees will often clean up EFB.

Figure 12 SHB in advanced stage “sliming” comb.

(Photo courtesy Steve Seigler.)

Assessing Signs of Varroa Mites

Are there signs of varroa mites such as “snott” brood, varroa visible on drone brood, or deformed wings? “Snott” brood is present when many larvae brood are white and flowing in the cell bottoms. Often in Varroa loaded colonies, you can see varroa mites on a drone pupa when it is removed. Bees with deformed wings are also a sign of heavy Varroa mite loads that have resulted in Deformed Wing Virus (DWV).

An alcohol wash or some other method of determining the colony’s mite load should be done to determine your colony status. I refer you to Randy Oliver’s https://scientificbeekeeping.com/ website for further information on determining your colony’s Varroa mite status.

Summary

Observation of what is going on in a colony is key to determining the colony’s status. If and when the colony swarmed or superseded the queen, if the colony has wax moths or small hive beetles, if you have a laying worker situation, and if you have Varroa mites are all important in assessing the colony’s health, and this assessment will assist you in your treatment and remedy efforts for the colony.