By: Darlene Bentley

A little over two years ago we settled with our bees into a valley home near the northern end of a protected, undeveloped lake, part of thousands of acres of land owned by the people of New York State.

The natural area surrounding us supports an abundance of animal life and a diversity of native and introduced plant species. Many of these plants are beneficial to pollinators. These include joe-pye-weed, boneset, bird’s foot trefoil, chicory, skunk cabbage, mints, thistle, Queen Anne’s lace, yarrow, sumac, Japanese knotweed, and poison ivy, as well as woody trees and shrubs like hawthorn, serviceberry, ninebark, locust, black cherry, black walnut, basswood, maples and willows. Our small property – just under six acres – reflects the habitat diversity of the surrounding ecosystems. It contains a variety of microenvironments: wetlands, former fields in various stages of succession, mixed deciduous woodlands and small stands of mature spruce and Scots pines.

The natural area surrounding us supports an abundance of animal life and a diversity of native and introduced plant species. Many of these plants are beneficial to pollinators. These include joe-pye-weed, boneset, bird’s foot trefoil, chicory, skunk cabbage, mints, thistle, Queen Anne’s lace, yarrow, sumac, Japanese knotweed, and poison ivy, as well as woody trees and shrubs like hawthorn, serviceberry, ninebark, locust, black cherry, black walnut, basswood, maples and willows. Our small property – just under six acres – reflects the habitat diversity of the surrounding ecosystems. It contains a variety of microenvironments: wetlands, former fields in various stages of succession, mixed deciduous woodlands and small stands of mature spruce and Scots pines.

My experience with bees, gardening and native plants, and my beekeeping and life partner’s woodworking skills, computer expertise and patience with machines (and me), provides a solid skill base for what we hope to accomplish. Our goal is to develop and implement a land management plan that centers on our bees and our acquired acreage. Since the bees are a crucial component, as pollinators for a variety of crops, and as producers of honey, propolis and wax, our earliest tasks focused on setting the colonies into their new home: clearing an area for the apiary, establishing the footprint for a bee yard storage shed, and planning for an extraction and bottling area. By the end of our first year, we had also planted an abundance of edible and ornamental perennials, fruit and nut trees and bushes, and an extensive vegetable garden in a fenced acre clearing.

As we moved forward with our plans and refined our goals, the need for careful land management became increasingly evident. We wanted to grow a wide variety of edible and medicinal plants for personal use, while supplementing our incomes by selling surplus crops and value added products – helping to meet the growing demand for goods produced and distributed locally. We opted for a permaculture approach for land use, which would allow us to preserve existing pollen and nectar sources while providing opportunities for integrated edible and ornamental pollinator-beneficial plantings. It also fit well with our desire to protect and work harmoniously with pre-existing microenvironments, including the evergreen groves – half of the available land – and an established bog area.

In contrast to traditional farming methods, permaculture gardening preserves and manages natural habitats. Plants are strategically integrated into the existing environment based on their growing needs, and new planting areas are intentionally planned to mimic natural ecosystems – creating species rich environments where plants, animals and decomposers assume crucial niches in an integrated forest-like environment. Trees provide shade and forest litter to low growing plants, which suppress weeds, deter pests and provide beneficial nutrients to build the soil. Once established, these forest gardens function as self-contained polycultures, requiring less maintenance than traditional monoculture plantings. The diversity of species in forest gardens creates an ecological balance that, under ideal circumstances, fosters healthy, disease-free plants, attracts and supports beneficial insects, and maintains habitat for predatory animals. This is part of an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) based approach that also includes more direct interventions, including hand picking of pests and the use, if needed, of organic pesticides as viable alternatives to synthetic pesticides – which can contaminate food supplies and kill beneficial insects, including honey bees.

Preserving existing woodlands provides aesthetic as well as ecological benefits. When we first saw the property, we were attracted to the beauty of the Norway spruce groves; we dreaded removing any of these trees. Originally part of a Christmas tree farm, many of the spruce now stand eighty to ninety feet tall, creating a densely shaded area of understory that supports ferns, fungi, moss, clusters of Jack in the pulpit and ground dwelling amphibians, such as the yellow-spotted salamander and red-spotted newt. The high canopy supports owls, pileated woodpeckers, flickers, migratory songbirds, red-tailed hawks, tree frogs, bats and, unfortunately, squirrels. One of our first challenges was to balance the preservation of these unique microenvironments, and the species dependent upon them, with our need for sunlight – both for sun-loving plants and for the bees.

Preserving existing woodlands provides aesthetic as well as ecological benefits. When we first saw the property, we were attracted to the beauty of the Norway spruce groves; we dreaded removing any of these trees. Originally part of a Christmas tree farm, many of the spruce now stand eighty to ninety feet tall, creating a densely shaded area of understory that supports ferns, fungi, moss, clusters of Jack in the pulpit and ground dwelling amphibians, such as the yellow-spotted salamander and red-spotted newt. The high canopy supports owls, pileated woodpeckers, flickers, migratory songbirds, red-tailed hawks, tree frogs, bats and, unfortunately, squirrels. One of our first challenges was to balance the preservation of these unique microenvironments, and the species dependent upon them, with our need for sunlight – both for sun-loving plants and for the bees.

Torrential rains and flooding conditions that hit our area two days after we purchased the land provided us some direction. When water from a small stream along the edge of the property changed course, it flooded the northern spruce grove and left several large spruce in the adjacent clearing standing in two feet of water. We removed the cluster of trees in this open area, and also cleared several wonderful trees that divided this area and the other open area to the south – the only area that receives six or more hours of sunlight daily. We removed a few additional trees that were crowding healthier spruce or were encroaching on the small number of mature black cherry and black walnut trees at the edges of the evergreen stands. Our initial hesitation to remove any of these majestic individuals was mediated by the natural changes resulting from the storm, planned supplemental plantings, the benefits of thinning around deciduous trees and our plans to use this harvested wood on the property. We had also discussed building a pond for habitat and irrigation; we now had a pond location.

Torrential rains and flooding conditions that hit our area two days after we purchased the land provided us some direction. When water from a small stream along the edge of the property changed course, it flooded the northern spruce grove and left several large spruce in the adjacent clearing standing in two feet of water. We removed the cluster of trees in this open area, and also cleared several wonderful trees that divided this area and the other open area to the south – the only area that receives six or more hours of sunlight daily. We removed a few additional trees that were crowding healthier spruce or were encroaching on the small number of mature black cherry and black walnut trees at the edges of the evergreen stands. Our initial hesitation to remove any of these majestic individuals was mediated by the natural changes resulting from the storm, planned supplemental plantings, the benefits of thinning around deciduous trees and our plans to use this harvested wood on the property. We had also discussed building a pond for habitat and irrigation; we now had a pond location.

Even with the removal of the spruce trees, the property is still dominantly shade or partial sun. We set the apiary up along the edge of our deciduous woods, which gets the morning sun (once the sun rises above the spruce stand) and remains sunny until early evening. To make the best possible use of the remaining portion of this largest clearing (less than an acre), we established a garden directly in front of the colonies. This places a variety of crops that need pollination within close proximity to our bees. It also puts us right in the bees’ flight paths while working in the garden. To mediate this, our earliest permanent plantings included currents, raspberries and paw paws, placed between the planting beds and the apiary to alter the bees’ flight paths. This year, we also set in a row of grapes to complete this boundary.

Even with the removal of the spruce trees, the property is still dominantly shade or partial sun. We set the apiary up along the edge of our deciduous woods, which gets the morning sun (once the sun rises above the spruce stand) and remains sunny until early evening. To make the best possible use of the remaining portion of this largest clearing (less than an acre), we established a garden directly in front of the colonies. This places a variety of crops that need pollination within close proximity to our bees. It also puts us right in the bees’ flight paths while working in the garden. To mediate this, our earliest permanent plantings included currents, raspberries and paw paws, placed between the planting beds and the apiary to alter the bees’ flight paths. This year, we also set in a row of grapes to complete this boundary.

In keeping with the permaculture approach, the clearing is now planted with small fruit and nut trees, with an understory of bushes and raised perennial and annual vegetable beds and herbal ground covers. Efficient integration of plantings includes both vertical plantings and ground covers. A tall ash tree serves as a pole for five varieties of hops plants, and a large black cherry serves as a support for hardy kiwi. The barrier fence that protects the garden from deer (with the help of the dogs) provides support for grapes, currents and mulberries. Ever bearing strawberries find a niche beneath dwarf cherry trees. Dense mats of five different thymes have been established under the blueberry bushes, suppressing weeds and serving as a deterrent for insect pests. Lavender serves a similar function under the hazelnuts and filberts. Other aromatic herbs, which also serve as deterrents to insect pests, are interspersed among the rotating vegetable planting beds. Annual beds and areas where low growing vegetation is not well established are mulched with wood shavings from treetops, brush, and pruned branches harvested on site. These mulches mimic forest litter layers, providing habitat for earthworms and other forest decomposers, conserving moisture and insulating plant roots. As fruit trees and bushes mature, and low growing perennials become established, this half-acre area will produce a wide range of fruits and vegetables, as well as many culinary and medicinal herbs.

In keeping with the permaculture approach, the clearing is now planted with small fruit and nut trees, with an understory of bushes and raised perennial and annual vegetable beds and herbal ground covers. Efficient integration of plantings includes both vertical plantings and ground covers. A tall ash tree serves as a pole for five varieties of hops plants, and a large black cherry serves as a support for hardy kiwi. The barrier fence that protects the garden from deer (with the help of the dogs) provides support for grapes, currents and mulberries. Ever bearing strawberries find a niche beneath dwarf cherry trees. Dense mats of five different thymes have been established under the blueberry bushes, suppressing weeds and serving as a deterrent for insect pests. Lavender serves a similar function under the hazelnuts and filberts. Other aromatic herbs, which also serve as deterrents to insect pests, are interspersed among the rotating vegetable planting beds. Annual beds and areas where low growing vegetation is not well established are mulched with wood shavings from treetops, brush, and pruned branches harvested on site. These mulches mimic forest litter layers, providing habitat for earthworms and other forest decomposers, conserving moisture and insulating plant roots. As fruit trees and bushes mature, and low growing perennials become established, this half-acre area will produce a wide range of fruits and vegetables, as well as many culinary and medicinal herbs.

Ecological restoration of existing habitats is beneficial to native species and can provide additional opportunities for integrated plantings. The deciduous forest adjacent to the apiary – predominantly ash interspersed with black locust, black cherry and hawthorns – had become overgrown with Japanese Honeysuckle, multi-flora roses and garlic mustard. Removal of these invasive plants benefited the existing lady ferns and Jack in the pulpits. It also exposed fertile mounds of substrate – formed by decomposed logs overlaid with accumulated deciduous leaves and decomposing herbaceous plant material. This exposed soil understory provided an ideal habitat for culinary and medicinal herbs that prefer or are tolerant of the partial shade and moist woodland soils. We planted these fertile mounds with Goldenseal, Black and Blue Cohosh and Ginseng, marketable native herbs. Closer to the bees, we planted European and American Elderberry (for food and bee forage), and we interspersed the existing ash grove with Carpathian walnut and butternut trees. Given the likelihood of the ash trees succumbing to emerald ash borer (EAB), these newer plantings of trees and shrubs will form a replacement forest canopy to shelter shade-loving natives (including the newly established medicinal herbs) and provide plant litter for protective mulch and nutrient enrichment. The removal of the invasive species and selective replanting diversified the existing microculture, allowing existing native ornamental species to thrive, while providing additional space for select plantings of edible and medicinal plants.

Ecological restoration of existing habitats is beneficial to native species and can provide additional opportunities for integrated plantings. The deciduous forest adjacent to the apiary – predominantly ash interspersed with black locust, black cherry and hawthorns – had become overgrown with Japanese Honeysuckle, multi-flora roses and garlic mustard. Removal of these invasive plants benefited the existing lady ferns and Jack in the pulpits. It also exposed fertile mounds of substrate – formed by decomposed logs overlaid with accumulated deciduous leaves and decomposing herbaceous plant material. This exposed soil understory provided an ideal habitat for culinary and medicinal herbs that prefer or are tolerant of the partial shade and moist woodland soils. We planted these fertile mounds with Goldenseal, Black and Blue Cohosh and Ginseng, marketable native herbs. Closer to the bees, we planted European and American Elderberry (for food and bee forage), and we interspersed the existing ash grove with Carpathian walnut and butternut trees. Given the likelihood of the ash trees succumbing to emerald ash borer (EAB), these newer plantings of trees and shrubs will form a replacement forest canopy to shelter shade-loving natives (including the newly established medicinal herbs) and provide plant litter for protective mulch and nutrient enrichment. The removal of the invasive species and selective replanting diversified the existing microculture, allowing existing native ornamental species to thrive, while providing additional space for select plantings of edible and medicinal plants.

The alignment of plant needs with existing environmental conditions is key to establishing native or introduced beneficial plants to a new area. Carefully planned introduction of edible crops in all available microenvironments maximizes potential harvests, while protecting existing habitats and pollinator forage. As we continue to clear invasive plants from other areas of the property, we are exploring additional planned plantings that compliment products from the hives, increasing our ability to establish a nutrapharmaceutical niche market centered on the bees. A larger, mostly shaded area has been interspersed with serviceberries, buttonbush, spicebush, high bush cranberries, viburnum and pussy willows to supplement existing native bushes. Edible cranberries will be introduced in a small sunny bog clearing that currently supports forget-me-nots, skunk cabbage and marsh marigold – which can remain as beneficial ground cover encircling the cranberry plantings. The vernal pools that form water “pathways” through the cranberry plantings will continue to provide habitats for reptile and amphibian populations – which help to keep insect and rodent populations in check. At this point in human environmental history, when so many invasive species have been introduced – accidentally or intentionally – into ecosystems that have been repeatedly altered by human intervention, planned land management can help some of these sensitive areas adapt to change, while still providing potential growing areas for suitable crops.

Some of our restorative interventions are more intensive, altering the existing landscape and creating new habitats. Our pond is one example; it replaces a lawn area– a labor-intensive ornamental monoculture. The pond basin will capture water that flows off the hills to the east – significant during major rain events – with the overflow feeding back into the wetland areas below. The pond basin is divided into two sections – approximately three quarters of an acre total area. At eighteen feet, the larger pond area is deep enough to support a small population of large mouth bass and bluegills for food. Water plants, established on ledges in the pond’s dike, will provide protection for minnows and bass eggs. Native crayfish – which bass eat – are already moving into the waterfall areas, where rocks are interspersed with naturalizing plants to minimize erosion. Once the pond is fully saturated and filled, cool water from the deep end will be pumped into a constructed wetland area adjacent to the upper pond, which will serve as a settling pool and natural filter. Bog plants established in this area will include edible ostrich ferns – valued for their gourmet fiddleheads. A sunny, sloped area near the lower pond has been planted with sea buckthorn – another plant with nutrapharmaceutical potential, and a Rosa rugosa patch on an earth berm will provide rosehips for tea – to pair with honey, of course. Water will be pumped from the pond for irrigation, including frost protection for the cranberries. What was once a large area of grass is evolving into a series of microhabitats that will support a wide assortment of introduced and native plants and animals.

We are also landscaping areas around the pond with cut flower ornamentals, which will provide supplemental income to complement honey sales, while providing additional sources for pollinator forage. Many of the newer, showier hybrid cut flower varieties have the pollen, nectar or fragrance systematically bred out of them and are not beneficial to honey bees. There is an abundance of ornamental varieties that pollinators love. In choosing ornamental varieties, we are balancing perennial beds of popular cut flowers with nectar and pollen plants that supplement our bees’ wild forage. We had already planned for some “cultivated” pollinator friendly native wildflower areas in woodland borders, many of which can be used as cut flowers. We also chose varieties of ornamental alliums, asters, yarrow, milkweed, sunflowers, and mints – that have multiple smaller flower clusters favored by honey bees and other pollinators. Planting concentrated areas of select varieties that bloom at varying times provides additional forage near the colonies to help bees span periods of dearth. This includes an abundance of woody ornamentals that thrive in wet and semi-shady environments and are favored as cut flowers and as pollen and nectar sources.

Supporting existing native species and diversifying plantings beneficial to bees is just one aspect of our sustainable use of the land. We are also managing our small stands of conifers and hardwoods. My partner’s skill in woodworking, which I am gradually acquiring, provides avenues for creative presentation of products and for reducing woodenware costs. He has already designed and fabricated double-screened boards for overwintering the bees and a wooden honey bee bookmark. We used some of the spruce for a sugar feeding station we designed and built – using up-cycled plastic nut containers to hold the syrup – and in the construction of our bee-equipment shed (the shed’s windows and doors are salvaged and are framed with leftover oak barn boards we found on the property when we moved in). Our mature ash will provide additional lumber resources as these trees succumb to EAB. Other mature trees will be selectively harvested due to declining health or competition, part of an inevitable evolution in our changing natural environment.

The bees remain central to our life and our future goals; their care is paramount to our success. We plan to make additional splits from our survivor stock and graft queens summer 2017 to expand our apiary, slightly (we recently took the Penn State Queen Rearing Course to learn more about this and get some hands on experience). Making splits will be part of our apiary management plan. In additional to providing increase colonies and replacements for winter losses, it also breaks the brood cycle, limiting the potential for Varroa destructor to reach threshold levels in the colonies. Combining this with drone frame mite traps reduces mite counts, allowing colonies to remain disease free. With these strategies and careful selection of hygienic bees from survivor stock, we may be able to avoid treating colonies for mites. We have also planted European pennyroyal – a creeping mint with pest deterrent qualities – below the hives to deter weeds. The essential oils derived from these plants are used in some organic mite treatments, and gathering their pollen may help bees combat mites. Maintaining smaller colonies likely reduces honey yields, but allows us to create a local niche market for untreated honey, propolis, candles, and value added herbal products.

The bees remain central to our life and our future goals; their care is paramount to our success. We plan to make additional splits from our survivor stock and graft queens summer 2017 to expand our apiary, slightly (we recently took the Penn State Queen Rearing Course to learn more about this and get some hands on experience). Making splits will be part of our apiary management plan. In additional to providing increase colonies and replacements for winter losses, it also breaks the brood cycle, limiting the potential for Varroa destructor to reach threshold levels in the colonies. Combining this with drone frame mite traps reduces mite counts, allowing colonies to remain disease free. With these strategies and careful selection of hygienic bees from survivor stock, we may be able to avoid treating colonies for mites. We have also planted European pennyroyal – a creeping mint with pest deterrent qualities – below the hives to deter weeds. The essential oils derived from these plants are used in some organic mite treatments, and gathering their pollen may help bees combat mites. Maintaining smaller colonies likely reduces honey yields, but allows us to create a local niche market for untreated honey, propolis, candles, and value added herbal products.

Sharing borders with undeveloped state lands provides protection from synthetic pesticides and other harmful consequences of increased human migration into rural areas and offers bees a greater diversity of forage. There are also inherent disadvantages, including mammal pests that can present challenges in small garden landscapes. Careful planning is needed to find a balance between our goals and the needs and protection of our small acreage and its many inhabitants. We are open to seeing how we will evolve as we settle onto the land and grow our business, along with our apiary. As forage areas decrease, and the challenges associated with keeping bees increase, we need to explore new, and old, ways of preserving the habitants that benefit our bees. A permaculture approach to land management maintains diverse foraging areas that support honey bees and other pollinators, while increasing the potential yield for specialty crops on smaller land areas. Moving away from large apiaries and fostering a network of smaller beekeepers, as part of the expanding locally produced food and craft market, is one way for beekeepers, and the bees, to adapt and survive.

Sharing borders with undeveloped state lands provides protection from synthetic pesticides and other harmful consequences of increased human migration into rural areas and offers bees a greater diversity of forage. There are also inherent disadvantages, including mammal pests that can present challenges in small garden landscapes. Careful planning is needed to find a balance between our goals and the needs and protection of our small acreage and its many inhabitants. We are open to seeing how we will evolve as we settle onto the land and grow our business, along with our apiary. As forage areas decrease, and the challenges associated with keeping bees increase, we need to explore new, and old, ways of preserving the habitants that benefit our bees. A permaculture approach to land management maintains diverse foraging areas that support honey bees and other pollinators, while increasing the potential yield for specialty crops on smaller land areas. Moving away from large apiaries and fostering a network of smaller beekeepers, as part of the expanding locally produced food and craft market, is one way for beekeepers, and the bees, to adapt and survive.

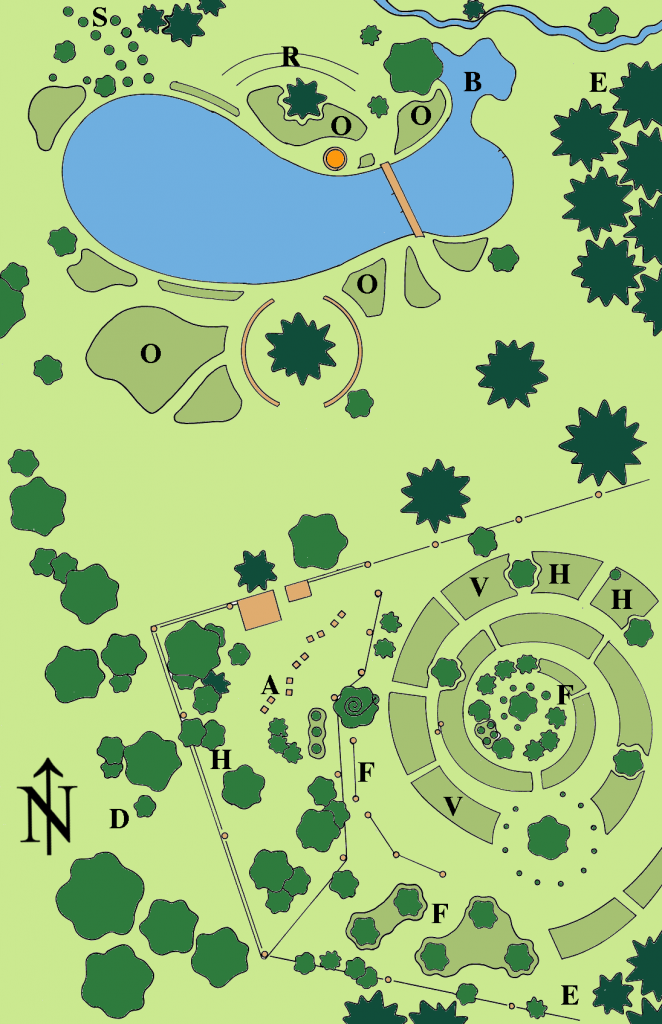

B – Bog

D – Deciduous Forest

E – Evergreen Forest

F – Fruit

H – Herbs

O – Ornamentals

R – Rosa rugosa

S – Sea buckthorn

V – Vegetables