A Guide To Asian Hornets That Affect Honey Bees

By: Paul Kozak and Gard Otis

2019 will be remembered as a significant year for new honey bee pests in North America, as two species of Asian giant hornets were reported and confirmed for the first time in the province of British Columbia, Canada, and across the border in Washington State, USA.

What are hornets?

First, what are “true hornets?” Hornets constitute a taxonomic category of wasps in the genus Vespa. They live in relatively large colonies composed of a queen and between a hundred to a few thousand workers, depending on the species. The workers forage for meat, typically preying upon other insects or carrion that they feed to their larvae, as well as rotting fruit, tree sap, and other sugary substances that serve as sources of energy for the adults. Hornets build their nests either suspended above the ground or in a cavity in the ground, and are surrounded by a papery envelope made from wood fibers. Colonies are initiated by single overwintered queens in early Spring. The number of workers increases exponentially over the summer, peaking in early Fall. At that time, colonies switch from rearing worker wasps to rearing new queens and males that emerge and mate. Only young mated queens overwinter in a hibernation-like state in a protected location for the winter. Their colonies in most cases expire by the onset of Winter. The species survives through the overwintered queens that emerge the following Spring and initiate the next cycle of nests. This annual cycle will be familiar to most as it is similar to our native species of social wasps – the paper wasps, yellowjackets, and bald-faced hornet.

All of the species of “true hornets” (members of the genus Vespa) are endemic (native) to Eurasia and northern Africa; none are native to North America. A few species are considered serious predators of European honey bees, the type of bee managed by beekeepers in North America. Because of their potential seriousness to managed honey bees, two species of Asian hornets, Vespa mandarinia and Vespa velutina, have garnered attention due to their presence in North America and Europe, respectively. Two additional species, Vespa soror and Vespa simillima, are a potential concern to beekeepers in North America should they be introduced and become established here.

Figure 1. The two species of Asian giant hornets, Vespa mandarinia (left; 18 Sept. 2019, Nanaimo, B.C.; photo courtesy of the Washington State Department of Agriculture) and Vespa soror (right; 10 May 2019, Vancouver, B.C.; courtesy of Paul van Westendorp, Provincial Apiculturist, British Columbia). Note the exceptionally wide head and lengthened side of the head capsule behind the eyes that is characteristic of these two closely related “sister” species.

The Asian Giant Hornets (AGHs), Vespa mandarinia and Vespa soror

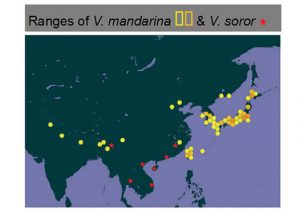

Vespa mandarinia is native to temperate regions of Asia, including northern India, large parts of China, and Japan. The “southern Asian Giant Hornet” Vespa soror inhabits somewhat warmer regions of Asia including Hong Kong and most of Vietnam (see Figures 1 & 2). These two species are very closely related and their natural histories are nearly identical. New queens that have mated with a single male overwinter and initiate nests in spring on their own, usually in a cavity in the ground, although they may chose to occupy a hollow in a tree. During the Summer worker hornets predominantly forage for caterpillars and large web-building spiders, carrion, and other insects such as individual bees. However, in late summer and fall, when the hornets have large food requirements due to the large numbers of larvae that need to be fed, they begin to focus group attacks on social insect colonies. At that time, if a foraging AGH locates an active honey bee colony in a hive, it catches bees singly at first. Then after perceiving some cue, she may return to her nest to recruit her nestmates. Over the span of a few hours 20+ hornets congregate at the hive. In the case of Apis mellifera, the hornets then collectively attack the bees at the hive entrance, killing all the adult worker bees with their huge mandibles over the span of a few hours. The hornets occupy the hive for many days afterwards, foraging on honey bee brood and honey.

These two hornet species can be identified by their exceptionally wide heads, the wide edge of the head behind the eyes (Fig. 1) and their very large size: 40-50+ mm (up to two inches) in body length and 76 mm (three inch) wingspan. Along with their large size, they have a long stinger and large venom sac. Although their venom is not the most toxic compared to other wasps and bees, because of the amount of venom delivered when they sting, these hornets pose a serious hazard to humans, domestic animals, and livestock. They can kill humans who have stepped on a nest or who experience an anaphylactic reaction to the venom. Additionally, once AGHs successfully take over a colony of honey bees, the hornets in the bee hive become as aggressive as they would be at their own nest as they defend the food resource (bee larvae and pupae). At this time they pose a serious risk to beekeepers.

The reports of Vespa mandarinia and Vespa soror in the Pacific Northwest in 2019 (described below) were the first confirmations of these “Asian giant hornets” outside of Asia. The climate to the west of the Coast Range, Cascade Mountains and Sierra Nevada should be suitable for populations of these two giant Asian hornet species to develop there. Both species should also be able to survive in parts of eastern North America, with V. mandarinia in cooler regions than V. soror.

The name “Asian Giant Hornet” has been informally assigned to Vespa mandarinia. That choice of name is unfortunate because it obscures the fact that there is another AGH, Vespa soror, that is similar in all respects, including its attacks on honey bee colonies. Hopefully official common names will be designated for all of the hornets described here to avoid confusion in the future.

Figure 2. Distributions of V. mandarinia and V. soror in Asia where these two species occur naturally. (Maps from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, Copenhagen, Denmark [www.gbif.org, accessed 14 May 2019]).

Vespa velutina, the “yellow-legged hornet”, is another species endemic to Asia, including parts of India, Pakistan, Vietnam and Indonesia. It too has a closely related and extremely similar “sister” species, the “yellow hornet”, Vespa simillima, that inhabits somewhat cooler regions of Japan and far eastern Russia. These are large wasps by current North American standards, but much smaller than the “giant Asian hornets” described above. These hornets are often first detected by beekeepers because of their distinctive foraging behaviour at bee hives. Individual hornets hover conspicuously at the entrances of bee hives and catch returning forager bees (Figure 3). Once a yellow-legged hornet discovers a hive, it returns repeatedly to catch bees. Their predation on individual bees can weaken colonies and increase winter mortality. Moreover, colonies that are the focus of extended hornet predation experience “foraging paralysis:” worker bees become confined to their nests by hornets hovering nearby. The reduction in foraging can severely reduce honey production, even resulting in colony starvation. In parts of France, these hornets have caused the deaths of a large percentage of managed honey bee colonies.

Vespa velutina has become well established over much of western Europe. It was first detected in southwestern France, where it is believed to have arrived accidently via overwintering queens (or possibly nests) in pottery imported from Asia. Since its introduction in 2004, this hornet has expanded its range rapidly. It now inhabits nearly all of France and Belgium as well as the neighbouring countries of Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. It is has a high probability of surviving in the eastern USA from New York City to Oklahoma and south, and possibly northward into the Great Lakes region. If introduced to western North America, it could likely establish a population west of the mountains from Vancouver, B.C., to San Francisco and into the Central Valley of California.

A queen of Vespa simillima was collected years ago near Victoria, British Columbia, in August of 1977. Fortunately there have been no subsequent records of this species in North America. If introduced, the yellow hornet is expected to inhabit cooler regions further north of those described for V. velutina.

Figure 3. The Yellow-legged Hornet, Vespa velutina, hovering in front of a beehive in France, awaiting incoming foragers. Photos courtesy of Quentin Rome/Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France.

Asian hornets confirmed in North America in 2019 and 2020

Several observations of giant Asian hornets were made in North America during the 2019 beekeeping season. Because there has been some confusion surrounding these reports, we have summarized them here.

The first report was last May, when a huge hornet was caught near the Vancouver (B.C.) harbor. It was initially identified by Dr. Jun-ichi Kojima of Japan as Vespa ducalis, but later was confirmed to be a queen of Vespa soror by Dr. Kojima, Dr. Graham Thurston of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, and Dr. Lien T.P. Nguyen, a wasp specialist in Vietnam. There have been no subsequent reports nor evidence of any nests of this species having been established anywhere in North America.

In mid August, three large hornets were collected in Nanaimo, B.C., on Vancouver Island. They were identified as the Asian Giant Hornet, Vespa mandarinia. Following an intensive search of the area, a nest containing about 200 worker hornets was located in Robin’s Park, Nanaimo. It was destroyed on 18 September. DNA evidence suggests that nest was founded by a queen from Japan.

In late Fall of 2019, a photograph of Vespa mandarinia was taken by a resident of White Rock, B.C., close to the border with Washington State. Nearby in Washington state, two V. mandarinia hornets were reported near Blaine, Washington; DNA analyses suggest they likely originated from South Korea. Additionally, there were two reports of suspicious bee kills that may have been caused by AGHs in Washington State (near the communities of Custer and Clearbrook), but the cause of those bee kills could not be confirmed.

Extensive plans to monitor for and eradicate Asian hornets this year have been developed and are being enacted. Local beekeepers are networking with federal, provincial and local agencies to report sightings. In Washington, members of the public have volunteered to monitor hornet traps from mid-Summer into the Fall. At the federal level, both the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency have prepared risk assessments as well as monitoring programs. Already, as of early June, three AGH specimens, at least two of which were overwintered queens, have been collected. The first was on 15 May in Langley Township, BC, approximately 10 km (six miles) from the 2019 reports in White Rock and Blaine. The second was a dead hornet found on 27 May near Custer, WA, not far from one of the unverified reports from 2019. On 6 June, a third hornet was killed near Bellingham, WA, 24 km (16 miles) from the Custer report. Interestingly, a bee colony in Blaine was killed by Vespa mandarinia hornets in 2019; the beekeeper had kept two hornet specimens that he submitted to state officials in early June, 2020. Residents of Washington state have reported several hundred additional “AGHs”, but all of those so far have been identified as other species.

The presence of AGHs in British Columbia and Washington State this Spring, some of which have been confirmed to be mated queens, indicates that at least one hornet colony, and more likely two or more, produced new queens last Fall. These few hornets do not yet indicate that Vespa mandarinia has successfully established a sustainable population in the Pacific Northwest. That will depend on a number of factors: the numbers of queens that established nests in 2019, the genetic diversity of those queens, and the ability of the hornets to adapt to their new environment which will become evident from their success at establishing nests over the next couple of years. Survey results over the Summer and Fall of 2020 will provide a much clearer picture of the AGH population.

Figure 4. Various hornet traps and entrance protectors currently used in Japan. (Images courtesy of Dr. Masami Sasaki.)

The rest of North America

To date, there have been no confirmed cases of any species of Asian hornets anywhere in North America outside of the few locations in B.C. and Washington reviewed above. Beekeepers do not need to worry about moving Asian hornets with their hives as the hornets do not live in honey bee colonies. However, hornet queens wintering in various types of freight and packing material could be transported to North America from Asia (all four species reviewed here) or from Europe (in the case of the yellow-legged hornet). Once established in North America, they could be easily moved across the continent in the same way.

If any of these species becomes established, it will be very difficult to eradicate it. As a case in point, efforts to eradicate or reduce the rate of spread of the yellow-legged hornet in Europe have been expensive and largely ineffective. All four of these Asian hornet species have the potential to seriously affect honey bee populations and honey production should they become established in North America. In Japan, beekeepers who manage Apis mellifera colonies must install traps and “protectors” at hive entrances (Fig. 4) to capture Vespa mandarinia hornets attracted to the bee colonies. Traps and other protective devices suitable for North American beekeeping may become a standard part of beekeeping in the future if V. mandarinia or V. soror do become successfully established here. There is no effective trap or hive protector for yellow-legged hornets.

Figure 5. The European hornet (Vespa crabro; above) and bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata; below) should not be mistaken for any of the Asian hornet species. Photos courtesy of Stephen A. Marshall.

Another introduced Vespa species has been in North America a long time

North America has another introduced species of Vespa – the European hornet, Vespa crabro. Native to Europe, it was accidentally introduced to New York State more than 160 years ago. Today it is widely distributed over the northeastern portion of the U.S. as well as parts of southern Canada. It is a large wasp (25-35 mm) and consequently rather intimidating in appearance (Fig. 5) – but much smaller than the Asian giant hornets. However, it rarely stings people or attacks honey bees. In recent years, both beekeepers and members of the general public have frequently reported European hornet as Asian giant hornets. Additionally, the bald-faced hornet, Dolichovespula maculata (Fig. 5), not a true hornet (it is classified a different genus), is also regularly mistaken as an Asian hornet species.

Reporting observations of giant hornets

Unfamiliar species should be reported to authorities because such observations are often the way in which exotic pests are discovered and tracked. Beekeepers and other stakeholders should remain vigilant for new pests and diseases of honey bees that may be introduced to North America, such as the large wasps reviewed here, Tropilaelaps mites, and other pests. By being able to identify these potential pest species and being aware of their current distribution, biology, and habits, we become better prepared should we encounter a novel species. Photographs and specimens are especially important because it is impossible to confirm the presence of an Asian hornet or other exotic species without good evidence that can be confirmed by a trained specialist. In the case of hornets, you may submit your report to your local apiary inspector or apiary program, to the agency or ministry responsible for invasive species, or to an extension entomologist, depending on your home state or province and the reporting framework in place.

We all have a role to play in protecting our beekeeping industry by reporting our sightings to local, state/provincial, or federal agriculture personnel. Citizen scientists will undoubtedly play an important role in tracking the spread of Asian hornets in North America. We can all agree on one thing in this time of uncertainty – we do not want any of these species of Asian hornets to become established in North America!

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank many individuals who shared information with us, particularly Timothy Lawrence (Washington State University), Chris Looney and Sven-Erik Spichiger (Washington State Department of Agriculture), Jun Nakamura (Tamagawa University, Tokyo, Japan), Lien T.P. Nguyen (Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi, Vietnam), Masami Sasaki (retired from Tamagawa University, Tokyo, Japan), and Paul van Westendorp (Ministry of Agriculture, British Columbia). Photographs were shared by the Washington State Department of Agriculture; Paul van Westendorp, Vancouver, B.C.; Quentin Rome, MNHN, Paris; and Stephen A. Marshall, Guelph, Ontario. G. Otis recognizes the financial support of the National Geographic Society Committee for Exploration and Research, for funding to study the responses of Asian hive bees to attacks by Vespa soror and V. velutina in Vietnam, 2013. John Wenzel provided helpful comments on an early draft of the manuscript.

Selected References

Cobey, S., T. Lawrence, and M. Jensen (2020). The Asian Giant Hornet, Vespa mandarinia – Fact sheet for the Public and Beekeepers. Washington State University Extension (Washington State). https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/2091/2020/04/AGHPreReview7arFactsheet.pdf.

INPN (2020). Le frailon asiatique, Vespa velutina. (The Asian Hornet, Vespa velutina). Inventarie National du Patrimoine Naturel. (http://frelonasiatique.mnhn.fr/)

Reported Asian Giant Hornet sightings. (2020). Washington State Department of Agriculture. (https://agr.wa.gov/departments/insects-pests-and-weeds//insects/hornets/reported-sightings)

Matsuura, M., and S.F. Sakagami (1973). A bionomic sketch of the giant hornet, Vespa mandarinia, a serious pest for Japanese apiculture. Journal Of The Faculty Of Science Hokkaido University Series VI. Zoology 19(1):125-162. (https://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2115/27557/1/19(1)_P125-162.pdf

Schmidt, J.O., S. Yamane, M. Matsuura, and C.K. Starr (1986). Hornet venoms: lethalities and lethal capacities. Toxicon 24: 950-954.

USDA (2020). New Pest Response Guidelines. Vespa mandarinia. Giant Asian Hornet. (https://cms.agr.wa.gov/WSDAKentico/Documents/PP/PestProgram/Vespa_mandarinia_NPRG_10Feb2020-(002).pdf)