By: Andrea Quigley

Two months ago, we looked at the woes of Calabrian beekeepers facing bankruptcy as their apiaries were burned if the Small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, ‘the beetle’) was detected. This month we ask why it didn’t arrive in Europe sooner, what some neighboring countries are doing to protect themselves and the latest position in Italy.

Two months ago, we looked at the woes of Calabrian beekeepers facing bankruptcy as their apiaries were burned if the Small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, ‘the beetle’) was detected. This month we ask why it didn’t arrive in Europe sooner, what some neighboring countries are doing to protect themselves and the latest position in Italy.

Small Hive Beetle is indigenous to sub Saharan Africa, that is the land lying south of the Saharan desert including Southern Sudan1. There it co-exists with local strains of honey bee that have adapted to live alongside it. The beetle was first found in Egypt during Summer 2000 and was likely introduced by humans. The beetle’s range now includes the Nile delta(2) but, unsuited to arid climates, the dry soils and desert prevent it infesting a larger area of Egypt. Neither has it spread from Egypt to Israel, mostly due to the local geography. A large expanse of desert, some of it mountainous, spans across the region forming a natural barrier. Human activities that might have introduced the beetle to neighboring Israel have been restricted due to the political tensions between those countries. Had the beetle reached Israel, it is possible the beetle would have spread around the Mediterranean countries.

European countries observed the experiences of the United States and Australia, and planned accordingly. For example, in 2010, the UK made a formal analysis3 to consider how the beetle might arrive in the UK. The report concluded the key risks are:

European countries observed the experiences of the United States and Australia, and planned accordingly. For example, in 2010, the UK made a formal analysis3 to consider how the beetle might arrive in the UK. The report concluded the key risks are:

- “Movement of honey bees: queens and package bees (workers) for the purposes of trade.

- Movement of alternative hosts e.g. bumble bees for pollination purposes.

- Trade in hive products – e.g. raw beeswax and honey in drums.

- Soil or compost associated with the plant trade.

- Fruit imports – in particular avocado, bananas, grapes, grapefruit, kiwi, apples, mango, melons and pineapples – Small hive beetle may oviposit (lay eggs) on fruit.

- Movement on beekeeping clothing/equipment.

- Movement on freight containers and transport vehicles themselves.

- Natural spread of the pest itself by flight, on its own or possibly in association with a host swarm.”

The 2013 European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)(4) report analyzed the risks and likelihood of the beetle arriving in Europe. Clear knowledge gaps were noted. The review concluded “[more] research is needed to ascertain the risk of SHB entry via products such as ripe fruits and soil associated with plants.” This was compounded by the warning that “Accidental bee import (unintended presence of bees in a non-bee consignment) is associated with a high risk of entry… since an infested consignment might not be detected.” All too late now, given the belief is that the beetle arrived on ripe fruit in Gioia Tauro, Italy.

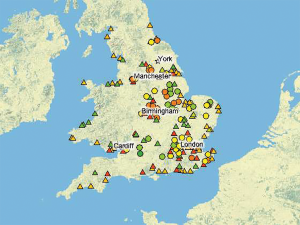

Figure 1. The risk areas for apiaries should an exotic pest arrive in England and Wales. Source: Beebase, Crown copyright.

Most countries have their own means of monitoring and dealing with “exotic” pests and diseases; “exotic” meaning those pests and diseases alien to a country. Within the EU, the member countries agree upon the appropriate control measures that each member must enforce. In the UK, this is done by the National Bee Unit (“NBU”), part of the Animal and Plant Health Agency. Teams of bee inspectors operate through the UK, although the Scottish and Northern Ireland inspectors report to the agricultural departments within their home governments. The inspectors and the NBU identify risk areas and place bait or sentinel hives nearby which are routinely checked. Likely places include airports, e.g. London Heathrow, ports and harbors, e.g. Dover, Liverpool and Southampton (Figure 1). If a small hive beetle were found then a rapid assessment would follow to uncover the extent and spread of any infestation under emergency measures. Steps would then be taken to eradicate or to contain and control the beetle depending on the degree of infestation.

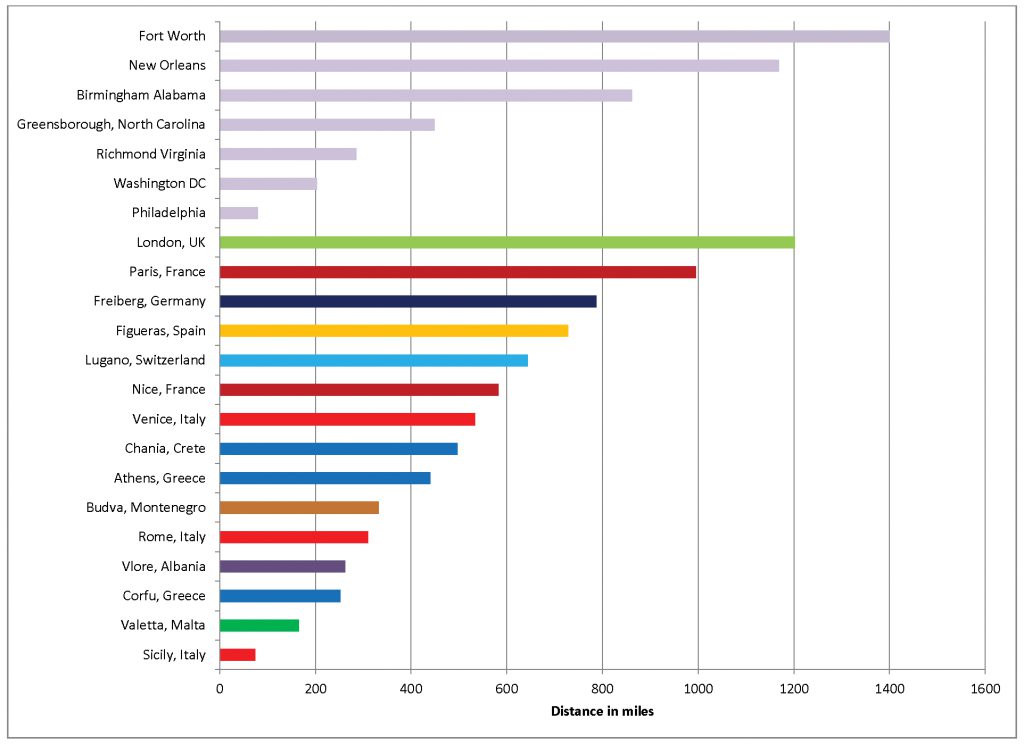

Figure 2.

With the discovery of the beetle in Italy, neighboring countries fear it will cross their borders and infest their colonies. Figure 2 shows relative distances as the crow flies from Calabria to locations in other European countries. These distances indicate the potential spread across Europe of this pest could take years and suggest infestation (at least in the short term) is not inevitable. Yet, the small islands of Malta and Gozo, with their own race of honey bees Apis mellifera Ruttneri, are closer to the outbreak than is the Italian capital of Rome. Understandably, the Maltese are really concerned. The ancient Greeks and Romans first named Malta as Melite (Μελίτη) and Melita respectively. These names mean “the land of honey.” To protect their land of honey, the Maltese issued an immediate and outright ban on movement of bees from Southern Italy, effective from 19 November 2014. A spokesman for the Maltese Plant Health Directorate said, “This beetle poses a serious threat to bees in Malta. For this reason, it has been decided to prohibit the importation in Malta of live bees from these affected areas, including bees used for the purpose of pollination.”

In the UK, beekeepers have watched recent developments with alarm. To a certain extent, the British Isles are protected since they are separate from the European mainland. Moreover London, UK, is some 1,202miles (1,938km) from Calabria; roughly the distance between New York City and New Orleans. However, fruit and plants (in soil) are regularly imported into the UK from Italy. One barrier to simply blocking movements of these products is a key EU principle “the freedom of movement of goods”. This means no EU state may block routing of goods into their country unless there is a clear threat to human health or the environment. Whilst beekeepers would argue that is the case, the UK government has not yet intervened to protect British bees. Many petitions have been raised, including one from the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association (“SBA”). On 2 December, the SBA wrote to the Scottish government to urge that “all possible measures are taken to prevent the introduction of small hive beetle into the UK. These should include a cessation of trade in live bees from the rest of Europe for 2015 until the true spread of the beetle is known.

Deep concerns have been raised by the British Beekeepers’ Association (“BBKA”) and others at the UK Bee Health Advisory Forum, a group of leading beekeeping groups and scientists working with government policy makers and bee experts. The BBKA says “[we have] urged restriction of the trade in plants, fruit and vegetables from the SHB exclusion zone in Italy, into the UK.” The BBKA is unhappy that plant health authorities, after consultation with bee health policy officials, state that “they do NOT have legal powers to stop the entry of plants, fruit and vegetables from Italy under plant health legislation.” The BBKA has urged them to “reconsider this aspect under the terms of animal health provisions”.

The BBKA also says that the additional measures taken are inadequate. These include (1) supply of a National Bee Unit advisory leaflet to the Fresh Produce Consortium who will pass on copies of this leaflet and inform their members of the risk of importing the beetle in their goods; and (2) HM Customs and Excise will monitor all arrivals to the UK together with the Plant Health and Seeds Inspectorate which inspects plants, fruit and vegetables on importation; they have been given information on how identify the beetle.

Until this outbreak, it was possible to freely move bees across borders within the EU provided a certificate of good health was available. With the current restrictions, the movement of bees is blocked from the affected region. The UK has almost no queen producers and the market for package bees is small. In 2014, UK beekeepers bought from Italy 1,767 queens (18% of all queens imported from the EU) and 1,202 package bees (85% of all packages imported from the EU). For many years, neither colonies nor package bees could be imported into the UK from countries outside the EU. EU law is similarly strict but also permits imports of bees from New Zealand. Given the Italian outbreak, UK bee inspectors re-inspected all bees imported from Italy during 2014. No beetles were found.

Some Swiss, German and Austria beekeepers move their bees to Italy each fall to avoid Winter colony losses and to build strong colonies for the Spring. Calabria is often chosen because good supplies of pollen and nectar are available for most of the Winter; with citrus trees flowering in January. During fall 2014, Swiss and German(16) beekeepers were advised if they have not taken their bees to Italy already then they should not do so. Uwe Büchner, spokesman for the Thuringen Ministry responsible for veterinary affairs, has asked beekeepers to leave their bees in Italy. In Austria, beekeepers are reminded that throughout Europe the beetle must by law be reported to the authorities. Beine Ӧsterreich (Austria Bee) advises its members that, in line with EU law, bees may not be moved from the “standstill” or red zone in Calabria and Sicily. Simply put, any bees migrated to Calabria for the Winter must remain there for fear of bringing the beetle home. On 12 December, the EU formally banned any movement of honey bees, bumble bees, bee equipment and hive products from Calabria and Sicily to anywhere in the EU or the European Economic Area (“EEA”). The EEA is free trade zone comprising 31 countries, including 28 EU member states and three members of the European Free Trade Association (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway). The ban permits movement of refined and processed beeswax together with honey intended for human consumption (but not comb honey). It expires on 31 May 2015 when it will be reviewed.

Both beekeepers and the officials in the affected area feel misunderstood. The beekeepers state they are doing everything they can to find the beetle and to comply with current measures but are fearful they will lose their livelihoods. In contrast, the inspectors have been accused of being too ready to burn everything and not doing enough to control the beetle. Both sides seem to be working hard and recent meetings may have helped ease tensions. New laws have been introduced to cover the beetle and its control. For example, penalties exist for failure to report presence of an apiary in the surveillance zone.

In Italy on 1 December, beleaguered beekeepers received some good news that they will receive compensation for the loss of their hives should they be destroyed to control the beetle. They may also receive compensation also for “loss of trade” and the “possible effects through loss of pollination.” Moreover since December 11, only one new case has been confirmed; the number of cases is now 60 infested apiaries. Over 3,500 colonies have been destroyed. On 11 December, Dr. Silvio Borrello, managing director for animal health, the Italian Ministry of Health, met with beekeeping groups and experts when beekeepers asked again for a switch to managing rather than eradicating the beetle. The Ministry of Health will reconsider its approach to incineration on 19 February which, coincidentally is the day when COLOSS’s new Small Hive Beetle task force will meet in Bologna. For now, the Ministry has reconfirmed that the existing crisis measures would remain in force. They remain hopeful that the outbreak will be eradicated. Yet it remains to be seen as the pollination season gets underway whether truly the beetle has been eradicated from Italy.

References

(1) El-Niweiri, M.A.et al (2008) Filling the Sudan gap: the northernmost natural distribution limit of small hive beetles. Journal of Apicultural Research 47(3): pp 184–185 DOI: 10.3827/IBRA.1.47.3.02

(2) Hassan, A. R. and Neumann, P, (2008) A survey of the small hive beetle in Egypt. Journal of Apicultural Research 47(3): 186–187 DOI: 10.3827/IBRA.1.47.3.03(

(3) Brown, M. and Learner, J. (2014) The Small hive beetle Aethina tumida (SHB) http://www.nationalbeeunit.com/downloadNews.cfm?id=125

(4) EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (2013) Scientific Opinion on the risk of entry of Aethina tumida and Tropilaelaps spp. in the EU. EFSA Journal;11(3): 3128