As the swarm winged over the highway, young bees carried passengers – mites holding tight to the bees’ fuzzy hairs with tiny gecko-like feet.

The travelers, and their riders, made a bee line for a distant hollow tree. As they settled in, the mites stayed bound to their hosts, biding their time astride their mounts.

A small voice spoke: This point in the story, said one of the mites, is where the writer would go on about the wonders of the bee, how scouts had selected the most ideal new home – not too big and expensive to heat and not too small for winter stores; how they build new comb, and the old queen starts to lay eggs in the hexagonal cells. She’ll write it as though they are special, but I’m here to tell you it rankles; bees are not more extraordinary than the rest of us. That writer is really just an anthropocentric beekeeper who loves nature as it serves her humans; she extols the bees and demonizes us mites; but we get that all the time. We’re used to it.

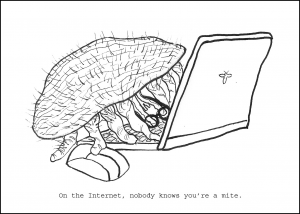

You may be wondering where that writer is while I so flagrantly usurp her voice. Well, she is tied fast to her chair in front of a computer screen where her eyes can see nothing but a thesaurus showing a list of synonyms for the word bigot. We had to call in a lot of favors to do that, but there are 48,200 species of mites around, 86 of them on bees, so we had help — some on leave from E.O. Wilson’s eyebrow. What I’m saying is we went deep, even reached out to some arachnids for the webbing. This was not our first choice, jumping genera: We first tried to unionize the bee mites, but most of them are scavengers, and they wanted to stay unnoticed.

This calumny starts with what they named us: Varroa destructor. The guy who did that, Dennis Anderson, is an Australian, so what does he care? We have avoided his continent, if he hasn’t noticed. It makes it sound as though we have set out to make a mess of things. Sure, we are immigrants, but so are the honey bees. And sure, things have gone too far; but the death in our wake, since we jumped to the European bee 35 years ago, is not entirely our fault any more than the forest is responsible for flooding after it has been clear cut. It’s not that we do not know how to behave like proper parasites; we have done it for millennia with their Asian sister species, and there are no complaints there. All we ask for is a cozy place to mate and a little hemolymph and vitellogenin, which is what the bees have for blood and stored food.

We are fed up with it, no pun intended. Now the writer, if she could, would no doubt continue by disrespecting our way of life. But what is our way of life but adaptive behavior?

I’ll need to excuse myself for a moment to sniff out the progress in this hive. Hmm, first pheromone is already coming from the new brood. That means some eggs have lain down to pupate at the bottom of the cells, and they are sending out their signal for the foragers to step it up and feed them. Self-centered little bastards (It’s true, there are 16 fathers among them). The bees have no idea that we mites can read their signals; they think they are transmitting through some kind of Enigma machine, but we are over here at Bletchley Park reading their messages like a newspaper. You’d think that they could smell us, too, but we can mimic the scent of the colony and move about freely in the dark; it’s like a cloak of invisibility, cool, huh?

Pretty soon, the larvae will send out another odor to signal that they are ready to get sealed up to pupate. I won’t get into how selfish that is, too, but they are telling the foragers to knock off bringing in food, with no regard for their hungry larvae siblings who are over there hollering “Feed me!” Just saying; we’re not the only ones playing me-first. That scent is our sign to jump into the cell. It’s a perfect place for me to hide down in the pool of milky food, breathing through a tiny tube, and lay my eggs. My daughters and I will emerge out of the cell on the bee, after the girls mate with their one brother, whose usefulness will have ended and thus his life. Now don’t go all anthropomorphic on me, we’re mites, and you notice I’m not commenting on your mating habits. Anyway, the bees kick out their drones; in our world, survival trumps compassion, and maybe you know about that, too.

We are not unusual among mites in that we digest our food outside our bodies, liquefying nutrients and sucking them up. We don’t mean to be spreading viruses this way, it’s just happens. Anyway, the bees were already weak and susceptible to infection before we ever came, their numbers plummeting since after World War II, when industrial chemicals were spread in the fields. And we surely had no intention of becoming so virulent; it’s not in our best interest. Left to ourselves we would be respectful of our hosts, as we have proven to be among feral bees in the wild that we coexist with in this country, taking a little hemolymph and space for some incestuous trysts but never taking them down. That would be evolutionarily stupid.

What’s happened is that some people who take it seriously, this directive to take dominion over the creatures of the earth, they have been poisoning us in their beehives. So what mites among us can bully through that? The most aggressive, resistant, deadly of us – so they keep needing new poisons and they keep choosing out our worst. In the 80’s it was 20 of us per 100 bees that could bring harm; now it’s three per 100.

When left on our own to work it out, the bees come to terms with us: some can read our codes, some can groom us off, and some beekeepers split colonies to make a break in our breeding. We’re good with that. In some places, where there has been no money or reach or intention to poison us, it takes a few seasons but we naturally come into balance with the bees and the beekeepers carry on. Some in this country are trying that, but they are taking it in the shorts from others.

Here in this tree hollow, a few of us philosophical mites are waiting to see if the barbarians among us will destroy us all – or if my daughters will live to coexist like their relatives on the feral bees in the Arnot Forest. So that’s it, I’ve had my say, a mites’ point of view. You can cut the writer loose now, my fellow Hymenopterites, but it might be wise not to mention this, as she is myopic on the subject.

M.E.A. McNeil is a journalist and Master Beekeeper who lives on a small Northern California organic farm with her husband. She can be reached at mea@onthefarm.com.