of Cultivated Flower Varieties

By: Laura Kraft

As gardeners become more interested in seeking out pollinator-friendly plants, the horticulture industry has a growing need to reliably measure and label plants for their ability to attract bees, butterflies, flies and other pollinators. This is particularly important for the flowering plants found most often at your local nursery, where years of hybridization and selection for certain characteristics may have influenced the plants’ attractiveness to local pollinator communities.

“There’s this disconnect between what’s labeled ‘Good for Pollinators’ and what’s actually good for pollinators,” says Emily Erickson, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher currently investigating population ecology at Tufts University. “There’s no real standard protocol to assessing what pollinator attractiveness means for nursery plants.”

Erickson’s postdoctoral research aims to tackle this problem. In a study she conducted with colleagues at Penn State University and published in May in the Journal of Economic Entomology, her team found that, for many plants, 10 minutes is a sufficient observation time to determine attractiveness to pollinators. Further, they found that these observations could be done successfully by even novice observers with just a little bit of training.

Verbena meteor shower. Photo by: Dr. Emily Erickson

Harnessing Citizen Science

Erickson is something of an expert at sitting in an oppressively hot field for hours, observing the pollinators arriving at flowers. She spent years doing exactly that during her graduate studies in the same lab group. When it came time to assess how to develop a protocol to get untrained individuals to make the same measurements that she had spent years practicing, she knew she had to ask for help. Erickson’s team found an incredibly enthusiastic group of volunteers from the local Master Gardener program.

“There’s a huge potential in this field for citizen science, but researchers can be wary of it because of concerns about observer error and data quality,” she says. In their new study, Erickson’s team set out to measure this error and to determine a minimum observation time for volunteer observers to quantify pollinator friendliness of new cultivars.

First, Erickson gave the volunteers a brief training on which pollinators they would likely encounter during the observation period but provided no additional help while volunteers observed on their own. As a comparison, Erickson’s team observed the same plant cultivars for the same periods of time to determine novice error.

The researchers also wanted to identify how long an individual plant should be observed to estimate different measures of attractiveness. To do this, Erickson watched each plant for 30 minutes and recorded which insects visited the plant and when. By spacing out observations over time and space, Erickson and colleagues learned some important parameters needed to measure pollinator attractiveness of cultivated plants.

In short, they found that a minimum observation time of 10 minutes accurately captures the pollinator visitation for a given cultivar and time of day. Furthermore, their team of Master Gardeners, despite having little to no experience observing pollinators prior, produced high quality observations after receiving a short training session.

Melissodes bimaculatus on portulaca (sundial light pink). Photo by: Dr. Emily Erickson

What Makes a Plant Pollinator-Friendly?

For nursery plants, attractiveness to pollinators is often considered a static property. One of the most interesting outcomes of this research is showing that plant attractiveness appears to change based on the time of day or other factors, such as what other plants are in the vicinity. In one dramatic example, the observers noticed that the flowers of Portulaca ‘Sundial Light Pink’ would open in the morning and close in the afternoon. Observers didn’t notice many pollinators visiting these flowers at all. As Erickson recalls, “I kept thinking I’m not going to get anything to this [flower]. I sat out there for 30 minutes and saw one syrphid fly. Then one day I show up and it was covered with the Melissodes bimaculatus.” Based on these observations, Portulaca ‘Sundial Light Pink’ appeared to be a cultivar that provides an inconsistent reward for pollinators and would not be suitable to be labeled ‘Pollinator-Friendly.’

In contrast, other flower cultivars had high pollinator abundance throughout the observation period. They seemed less affected by other background factors like time of day or nearby plants. These cultivars, which have consistent rewards for pollinators, would likely be more suitable candidates for the title of pollinator-friendly plants.

Additionally, Erickson’s group found that merely looking at pollinator abundance is an insufficient measure of pollinator attractiveness, since cultivars that attract different groups of pollinators tend to attract different numbers of visitors overall. For example, flowers in the study that attract mostly bees received many more visits in 30 minutes than those that attracted mostly flies or butterflies. If total visitor abundance is the only measure considered, an assessment of plant attractiveness may undervalue cultivars that provide resources to more diverse pollinators. Says Erickson, “I think just broadening our understanding of what plant value means beyond just ‘How many things overall does it attract?’ is a really important consideration going forward.”

Verbena Lascar ‘Mango Orange.’

Photo by: Dr. Emily Erickson

Developing Solutions for the Floriculture Industry

Erickson’s team worked closely with members of the floriculture industry when designing this research in the hopes of developing a standardized protocol that can be used to label new cultivars appropriately. The hope is that, in the future, pollinator attractiveness can be measured among other traits in breeding trials of new flower cultivars, allowing for more meaningful labeling to be used.

This will help gardeners and urban planners choose flower cultivars suited to supporting urban and residential pollinator habitats, particularly since cultivars, like fast fashion, are quickly replaced by the latest and greatest new blooms and often cannot be found again the next growing season.

Laura Kraft

Dr. Emily Erickson

Laura Kraft, Ph.D., is an entomologist, science communicator and world traveler currently based in Orlando, Florida. Email: laurajkraft@gmail.com.

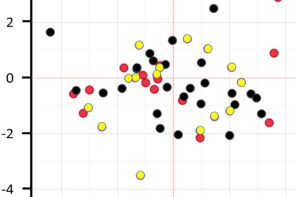

Photo Caption: The authors found significant differences in pollinator activity to closely related cultivars of flowers. For example, Verbena ‘Meteor Shower’ received lots of bee and butterfly visitors while Verbena Lascar ‘Mango Orange’ received very few visitors.

Originally published at the Entomological Society of America’s blog, Entomology Today.