Dwarf crested iris wildflowers. Credit: Getty Images

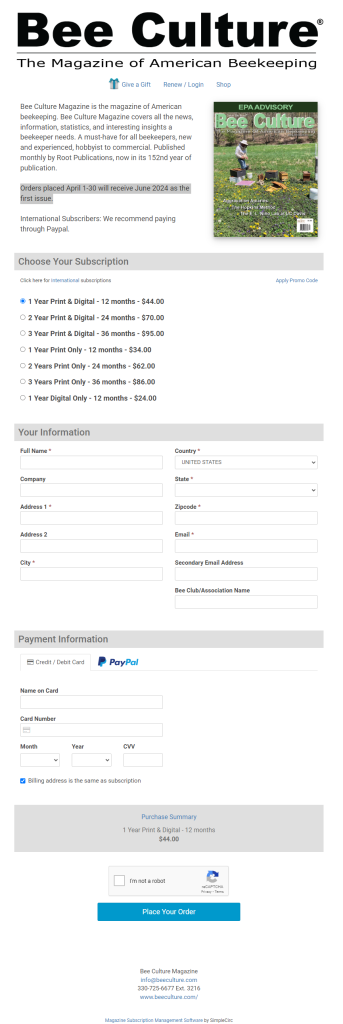

In Missouri, a Human ‘Bee’ Works to Better Understand Climate Change’s Effects

Researcher Matthew Austin has become a wildflower pollinator, sans the wings.

Shahla Farzan: This is Scientific American’s 60-Second Science. I’m Shahla Farzan.

Many plants and animals use temperature and other environmental cues like a calendar—letting them know when it’s time to bloom or find a mate.

But climate change is disrupting these natural rhythms worldwide, from songbird migration across North America to plankton growth cycles in Norway to a hillside of wildflowers in Missouri.

Matthew Austin: If we head on out, you can notice a number of different species that have popped up: dwarf crested iris, blue phlox, Canadian wood betony.

Farzan: Matthew Austin is a postdoctoral researcher with the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University [in St. Louis].

This patch of forest—about 40 miles west of St. Louis—is covered with native wildflowers throughout the spring and summer. But the timing of when they bloom has changed in recent decades, Austin says.

Austin: A warming climate is not only causing flowers to bloom earlier, but in many species, it’s also causing them to end flowering later.

Farzan: Missouri wildflowers are blooming up to a week longer than they used to, compared to data collected in the 1930s and 1940s. And that’s created a late summer pileup of species flowering all at once.

Meanwhile bumblebees and other pollinators are flitting from species to species, says Nicole Miller-Struttmann, a biologist at Webster University.

Nicole Miller-Struttmann: When a pollinator makes a decision about who it’s going to visit, that influences the pollen that they’re carrying on their body. And flowers, not too surprisingly, don’t really want pollen from another plant species.

Farzan: A flower that gets pollen from the wrong species might not be able to reproduce—or it could push some to self-pollinate—an extreme form of inbreeding.

To understand how this might affect reproduction, Matthew Austin has been pollinating hundreds of Missouri wildflowers by hand this year.

Some experimental flowers get pollen from their own species. Others get pollen from different plant species to simulate what’s happening now, as climate change causes that pileup of species blooming at the same time.

To keep pollinators from visiting his flowers, he slips sheer mesh bags over the buds before they open.

But just as he removes the bag to tap pollen onto the flower’s sticky stigma, a tiny bee lands on it.

Austin: Oh no, it just stuck right in there. A pollinator got in there when I had it unbagged. They’re sneaky. So this one will not be included, but thankfully, there’s another one.

Farzan: He moves on to the next flower, a human meticulously doing the work of a bee.

It’s a slow process—but Austin hopes the results will help us understand how climate change is reshaping this complicated ecosystem.

In Missouri, a Human ‘Bee’ Works to Better Understand Climate Change’s Effects – Scientific American