An Evolutionary Marvel

By: Ed Erwin

To appreciate the uniqueness of the female honey bee stinger, it’s important to understand how this complex and distinct appendage evolved. The first bee evolved from wasp-like ancestors who were predatory hunting insects which were abundant during the Jurassic Period, beginning approximately 201.3 million years ago to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 145 million years ago. The Cretaceous was a warming period of the earth with many changes in biological diversity including the first mammals and the first true flowering plants. During the Jurassic Period, most of the plants reproduced by transferring pollen through the effects of wind. Like most of the flowering plants of today, the flowering plants of the Cretaceous period needed help in transferring pollen. To take advantage of this protein source, the wasp began to evolve into a pollen-carrying bee.

As the earth warmed during the Cretaceous Period, and the warmer climate created flowering plants which needed to be pollinated, the bee was evolving to become the perfect pollinator. This early bee was different than the honey bee we know today, which evolved around 25 million years ago. The modern honey bee was one of the first bee species to live in a group and not in solitary isolation. Along with this unique adaptation came the evolution of the honey bee stinger, which is a unique feature, suggesting that this evolved once the honey bees became a distinct genus.

As the earth warmed during the Cretaceous Period, and the warmer climate created flowering plants which needed to be pollinated, the bee was evolving to become the perfect pollinator. This early bee was different than the honey bee we know today, which evolved around 25 million years ago. The modern honey bee was one of the first bee species to live in a group and not in solitary isolation. Along with this unique adaptation came the evolution of the honey bee stinger, which is a unique feature, suggesting that this evolved once the honey bees became a distinct genus.

The stinging apparatus of the honey bee is a modified ovipositor (egg laying tube) with associated venom glands that all bees have. In most insects, the ovipositor is used to lay eggs.

The ancient wasps, like the wasps of today, use their stingers as a weapon to paralyze or kill their victims. The honey bee stinger is a complex structure made of many parts and is used as a weapon to defend the hive or the bee itself.

Male bees, also known as drones, are larger and do not have stingers at all. The queen bee has a smooth stinger, which she can use as a weapon.

When a honey bee stings, it grips its prey with its legs and pushes backward, pointing the sting shaft at its victim. This action forces the rigid stinger to a vertical, downwards angle.

The female honey bee stinger is a complex structure. The honey bee stinger is composed of several distinct parts that work in unison. The stinger consists of three key parts: a sharp sting shaft, or stylus, with two paired, barbed lancets at regular intervals running backwards and forwards located along opposite sides of the stylus. The bee does not push the stinger in but it is drawn in by muscular articulation that controls the movement of the barbed slides. The lancets move alternately up and down the stylus. When the barb on one side engages and retracts so that the barb of one slide has caught and retracts, it pulls the stylus and the other barbed slide into the wound – effectively sawing into the flesh. As the other barb catches, it retracts up the stylus pulling the stinger further in. This movement is repeated until the stinger is fully engaged to its maximum depth. This process continues even if the stinger is detached from the abdomen.

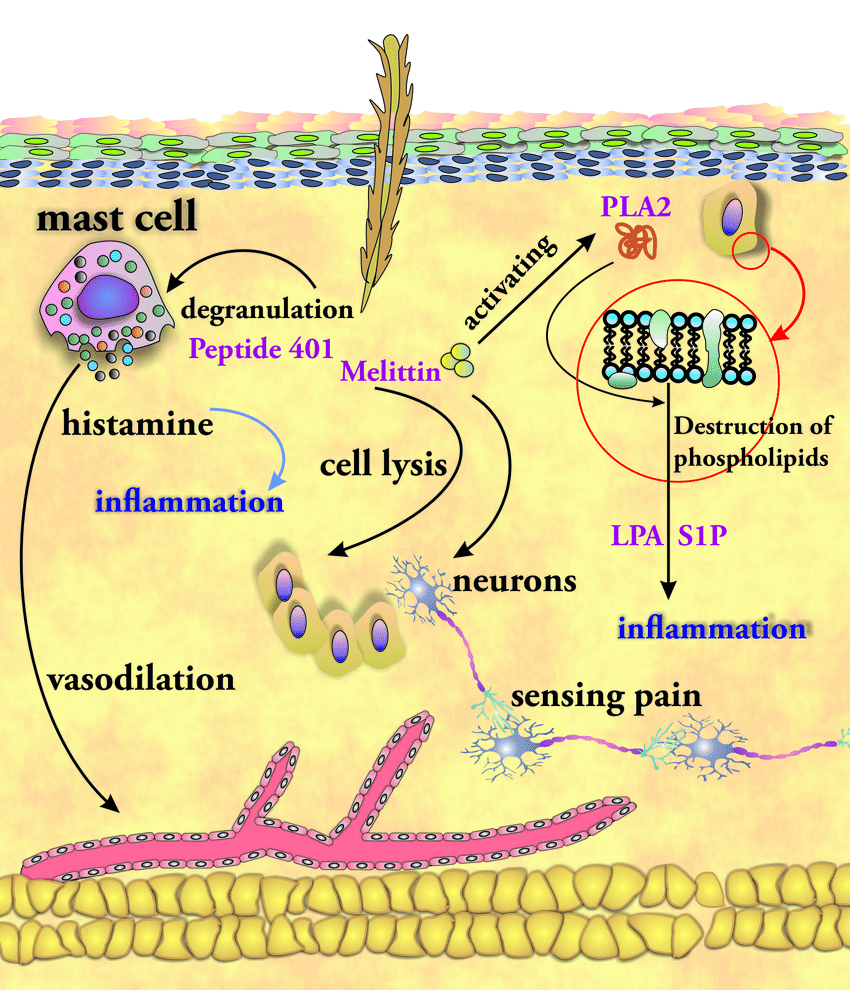

The stinger’s lethal venom, known as apitoxin, is a cytotoxic and hemotoxic bitter colorless liquid containing chemical compounds of proteins located in the venom gland, venom sack and bulb. Venom is 88 percent water, with fructose & glucose (sugars) and phospholipids (fat cells). The venom of the honey bee also contains histamine, mast cell degranulating peptide, melittin, phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. The main component of bee venom responsible for pain and itching is the toxin melittin, a basic peptide consisting of 26 amino acids. These small protein molecules rupture red blood cells and bursts other cells in the blood vessels and skin. Although melittin is the main component and the major pain producing substance of honey bee venom, histamine is also released and causes inflammation by dilating blood vessels causing swelling and redness. An enzyme known as hyaluronidase is also released. It digests and breaks down the tissue in the flesh. This causes an increased rate at which the venom can diffuse. The three proteins in honey bee venom, which are important allergens, are phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. When the bee injects the apitoxin into the victim, alarm pheromones are also released into the air alerting other bees to join in attacking the threat.

The stinger’s lethal venom, known as apitoxin, is a cytotoxic and hemotoxic bitter colorless liquid containing chemical compounds of proteins located in the venom gland, venom sack and bulb. Venom is 88 percent water, with fructose & glucose (sugars) and phospholipids (fat cells). The venom of the honey bee also contains histamine, mast cell degranulating peptide, melittin, phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. The main component of bee venom responsible for pain and itching is the toxin melittin, a basic peptide consisting of 26 amino acids. These small protein molecules rupture red blood cells and bursts other cells in the blood vessels and skin. Although melittin is the main component and the major pain producing substance of honey bee venom, histamine is also released and causes inflammation by dilating blood vessels causing swelling and redness. An enzyme known as hyaluronidase is also released. It digests and breaks down the tissue in the flesh. This causes an increased rate at which the venom can diffuse. The three proteins in honey bee venom, which are important allergens, are phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and acid phosphatase. When the bee injects the apitoxin into the victim, alarm pheromones are also released into the air alerting other bees to join in attacking the threat.

Bee venom is slightly acidic, and in most people causes only mild pain. However, more severe allergic reactions may occur in people with allergies to the venom components. Serious life-threatening anaphylactic reaction occurs in 0.8% of the population.

Several large muscles are used to facilitate the delivery of venom via the two pumps inside the venom gland. They, along with the venom storage sac, deliver the toxic venom to the stinger itself, which is only one or two millimeters in length. The sac contains about 1/50,000 oz of liquid venom. Depending on how long the stinger is allowed to pump venom, the amount injected is usually less than the 1/50,000 oz.

When the hive is attacked by other insects, bees can sting their foes multiple times, injecting venom and then removing the stinger safely after each stab. When a female honey bee stings a person, or an animal with flesh, it cannot pull the barbed stinger back out. As the honey bee flies away, the stinger tears off the body along with the venom sac, the muscular pumping mechanisms, parts of its abdomen, the digestive tract and nerves. The bee is disemboweled and massive abdominal rupture kills the honey bee. Although the bee is no longer connected, the stinger remains and continues to pump venom into the victim for 30 to 60 seconds.

Although there are thousands of species of bees, honey bees are the only bee species to possess barbed stingers and die after stinging.

Although there are thousands of species of bees, honey bees are the only bee species to possess barbed stingers and die after stinging.

Beekeepers know the main reasons bees become aggressive; include the need to protect their hive and honey, irritation of stormy weather and thunder, sensitivity to electromagnetic radiation, lack of nectar during the dearth, when a good honey flow stops abruptly and others, including Honey Bee Genetics. Beekeepers know that some hives are simply aggressive, which is usually the result of the genetics passed on by the queen to the entire colony of worker bees – a perfect example: Africanized Honey Bees. When bees become aggressive or need to defend their hive they use their stinger. Beekeepers know honey bees foraging for resources, such as nectar or pollen, rarely sting. The exception is if they are stepped on or feel threatened – so don’t swat foraging bees.

When people meet a beekeeper their first question is usually “have you been stung?” For most beekeepers the response is “Do you mean today?” For beekeepers, being stung on occasion is just part of the experience of beekeeping.