by Phil Craft

A beekeeper in Georgia writes:

Enjoy your column in Bee Culture very much. Got a problem. South GA-and probably lots of other places-was hit hard this year with small hive beetles. For various reasons, including being away from home for a period of time, I wasn’t able to get into my two hives for six weeks, and the little devils had a field day..

When I got back home, both hives had absconded, no bees left in the hives, and both were full of beetles and their worms. Honey residue had dripped throughout each box, out between boxes and all over the outsides. It’s taken me about a full week to scrape the fouled wax, etc. off the frames and foundation, all of which are plastic. I’ve been scrubbing the frames with water mixed with dish detergent and it works reasonably well, except it’s very slow.

A beekeeper friend suggested I clean everything with a bleach and water solution of 50-50 and then rinse off each frame eight to 10 times to remove the smell, otherwise the bees would probably reject the hive as a place to live. Another friend who has a pressure washing business said the bleach would leave a residue which would be next to impossible to remove. He suggested peroxide, which he uses in his business because it leaves very little residue, but is very effective-although quite expensive in the amount I might need.

I’d appreciate your thoughts on this ugly situation. It’s been a lousy year! Thanks for any suggestions you might send me.

Phil replies:

I commiserate with you. You describe very well the aftermath of a severe small hive beetle (SHB) infestation or, to be more precise, an out of control explosion of SHB larvae. In a healthy hive with a strong population, honey bees can control the beetles pretty well. They do this by restricting adult beetles to areas of the hive, such as the inner cover or empty comb, where they are cut off from the pollen and other food sources they need in order to reproduce. By this means a populous hive can tolerate a large number of beetles. It is their larvae and not the beetles themselves which cause all the damage. I often see dozens of adult beetles (mostly on the inner cover) when I open my hives, without seeing any of the carnage your two hives experienced.

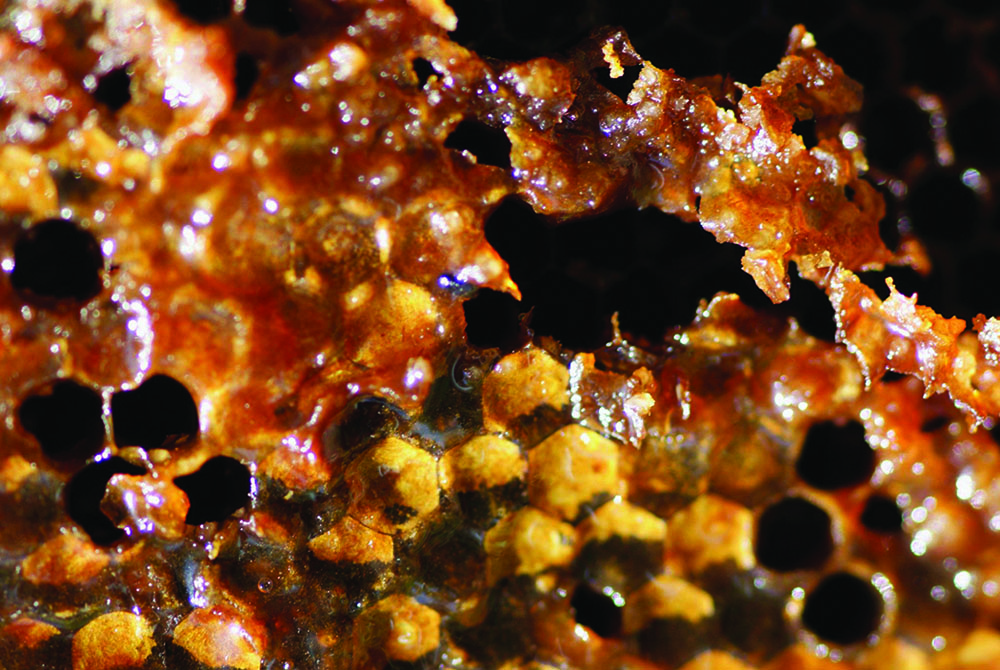

On the other hand, a weakened or underpopulated hive simply does not have enough bees to herd and contain beetles while also tending to the queen and brood, foraging, ventilating and guarding the hive, and performing all the other tasks which are part of the life of a colony. I am certain that some circumstance occurred, while you were unable to attend to them, to reduce the strength of your hives and allow the beetle larvae to get out of hand – perhaps the loss of the queen, or the consequences of a varroa mite problem. The explosion of SHB larvae results in badly damaged comb and, as you describe, fermented, ruined honey. The fermentation is caused by a yeast carried by both adult beetles and larvae. The final stage is the absconding of any remaining bees, leaving the beetles and larvae in sole possession to wreak the destruction that you found. Leaving you with the cleanup.

Damaged comb. photo by Mary K. Parnell

Which brings me to your question about how to deal with the mess and make your equipment usable again. I personally do not re-use frames (most of mine are wood), preferring to buy new ones instead of taking the time to clean up the old. However, a good scrubbing and scraping off of the damaged wax is all they need. A chemical such as peroxide or bleach is not necessary; a mild detergent works fine. Just scrub them up and let them dry. You might find it helpful to melt some beeswax and use a paintbrush to apply a thin coat to the plastic foundation.

Plastic foundation, as I am sure you know, comes with a film of wax which your scrubbing and scraping has most likely removed. Replacing it will help encourage new bees to draw out the comb next spring. If you are lucky enough to have caught some of the comb before it was badly damaged, you can clean it by gently agitating the frames in a bucket of soapy water, rinsing with a gentle spray from a water hose, and allowing them to dry. Not in direct sunlight of course; you do not want to melt the wax. Cocoon residues in the comb would be an indication that wax moths as well as SHB have been exploiting your weakened hives. The same guidelines for clean-up would apply.

I’m sorry you’ve had such a lousy time. Remember the slogan of the Brooklyn Dodgers of the ‘40s and ‘50’s when season after season began with promise only to end in disappointing post season losses to the Yankees: “Wait ‘till next year.”

A note to Bee Culture readers: I have written in more detail about the problems caused by SHB in columns of February 2014 and June 2013. Let me know if you would like a copy of these Q&A’s. If you are interested in more information on small hive beetles, I think one of the best written resources is from Mississippi State University. You can get it online at: https://www.extension.org/sites/default/files/SHB-Mgt-in-MS_2012_Sheridan-Fulton-Zawislak%20%281%29.pdf.

A beekeeper in Kentucky writes:

Hi, Phil. While observing a hive last Friday (late afternoon) I noted two things:

1) The bees were acting oppositional rather than cooperative, and it seemed they were pushing drones out of the hive.

2) I observed a worker carry out a large grayish larva that I think was a wax moth larva.

I am concerned about the wax moth possibility and what to do….

Phil replies:

In response to your first observation, forcing drones out of the hive is a normal behavior for this time of year. The ruthless efficiency of the hive requires the elimination of those members that do not contribute to the colony’s well-being. This includes adults damaged by disease or parasites, such as those with deformed wing virus. It also includes diseased brood, the removal of which we refer to as hygienic behavior – a trait which queen breeders select for because it helps control Varroa and brood diseases such as foulbrood and chalkbrood. In times of dearth, bees sometimes even remove healthy brood in order to reduce the drain on meager food resources. (Bee Culture readers: I discussed hygienic behavior in a November 2013 “Ask Phil” column. You can email me to get a copy.)

Drone pupa. photo by Mary K. Parnell

The only role of drones in a hive is to be available for mating with virgin queens. It follows that the need for drones coincides with periods of queen production. Colonies produce the first drones in the Spring several weeks before building the first queen cells in order to have an abundance of them by the time queens are ready to mate. The drones’ job remains important throughout the Summer until queen rearing tapers off (around September in most of the U.S.) At that point, they become superfluous – consuming resources while contributing nothing. The workers force them out to starve. No need to waste good food on those guys. Hives that are stressed by a shortage of food reserves may eliminate drones from a hive at any season, much as they remove healthy brood under the same circumstances: to reduce the need to feed unproductive members of the colony. However, considering the time of year (late September when I received this question), you are most likely seeing normal, seasonal, drone expulsion.

As to the larva you saw being carried out, you are going to have to open the hive to find out what’s going on inside. Its presence may indicate a weakened hive with a serious parasite problem, or it may merely be a case of a worker doing a routine housekeeping chore. Wax moths will multiply by what I call clandestine reproduction: a small number of moths in corners of the hive, doing little damage to the comb and not producing larvae in large numbers. A healthy colony can keep them in check, but can’t eliminate them completely. The beekeeper might never notice them unless something else causes the colony to weaken and the infestation gets out of hand. The larva you saw might have been one of a few produced by a stray moth which snuck into the hive. It is also possible that it belonged to a small hive beetle (SHB) instead of a wax moth. The larvae of these two pests can be difficult to tell apart unless you compare them side by side. My earlier comments pertain to both of these pests, but it is even more common to see an occasional SHB larva in a healthy colony. While a healthy colony can usually remove adult wax moths before they have a chance to reproduce, adult SHB are more difficult to expel and are more likely to be permanent squatters inside our hives.

Observations made at the hive’s entrance can give you clues about what is occurring inside, but for answers, you’re going to have to open it up. The first thing to look for is the number of frames covered by bees. A strong hive at this time of year should have bees on most of the frames. Look to see if you have eggs, larvae (honey bee larvae that is), and/or pupae. A queenless hive will have a dwindling population making it vulnerable to wax moths and small hive beetles as well as a host of other problems. In addition, take note of the number of frames of stored honey. There should be several. If the hive has a good population, developing bees, and food reserves, and if you do not see additional wax moth or small hive beetle larvae, don’t worry about the one you saw being carried out. Your hive should be fine.

A beekeeper in Nevada writes:

New (18 months) at this fascinating hobby of bee keeping. Q: I have a hive (my only one) that may not survive the winter here in Reno, Nevada. Maybe under 1000 bees left. Don’t know the reason, but was wondering if this late in the season, it is worth the gamble to re-queen, and if so, where can I obtain a new queen?

Phil replies:

Considering the time of year (late October when I received your question) and the number of bees in your hive, to purchase a queen would be a waste of money and a good queen. Even if the season were not so advanced – say late July or August – it would be a dubious strategy. If your estimate is accurate, there simply aren’t enough bees in the colony for it to build up to strength before Winter. New beekeepers tend to expend a lot of effort on lost causes, understandably since they have already invested time and money and don’t want to end up with nothing but an empty hive to show for it. As for me, I’m pretty ruthless when it comes to very weak hives. I shake the bees out on the ground in my apiary and store the equipment, including the drawn comb, to use another day.

IF the hive had more bees, and you thought it possible to save it, you would have to consider whether you could get the re-queened hive through the winter. When we discuss the necessary conditions for winter survival, we talk about three things:

•Health of the colony. The most common factor affecting health is the level of Varroa mite infestation. Mites shorten the lifespan of bees, so a high mite count could result in the bees’ dying before spring.

Food stores. The amount required can be as much as 100 pounds of honey in the far northern U.S., about 50 pounds in Kentucky, and probably less in your area.

•Strength of the colony. This is the criterion which relates directly to your question, though for the colony numbers to have diminished to the extent that you describe, some other factor must be present. Conventional wisdom is that a colony needs a deep hive body full of bees, or roughly about 20,000, going into winter. This number is an estimate which assumes ten frames of bees with about 2,000 bees on each frame.

•The thousand bees in your hive means that you are way short. If you had a second, stronger hive, I might recommend moving several frames of brood from it to the weaker hive and requeening, or better yet, combining the two hives. Unfortunately, that obviously is not an option for you. I’m glad to hear you describe beekeeping as a fascinating hobby. I hope you maintain your enthusiasm when you try again next year.

Your question brings up another issue that I face time and again when communicating with beekeepers concerning problems in their hives. Though your description of a hive containing “maybe under a thousand bees” worked fine to help me visualize your situation, most descriptions of hive populations are too vague and subjective to be helpful. When we refer to strong hives, we mean ones with enough bees to make honey, rear brood, and carry on all the functions of a colony – in other words a lot of bees. But what seems like a lot of bees to an overwhelmed new beekeeper may look altogether insufficient to me. How can we quantify what constitutes a strong hive? We obviously cannot count the bees. We could use the rule of thumb I referred to above and multiply the number of frames covered with bees by 2,000, but that’s just a guestimate, and I don’t think it necessary to come up with an actual number. I prefer just to count the number of frames (typically deeps) in a brood box which are literally covered with bees. A box with the equivalent of nine or ten full frames is a full box. A hive all of whose brood boxes are full is a full hive. This provides us with a quick and sufficiently accurate method of quantifying the strength of a colony. I find referring to the number of full frames in a hive to be useful, not only in communicating with other beekeepers, but also in evaluating my own hives. When I inspect hives in the early Spring, I take note of and record the number of frames covered with bees. Later, during follow-up inspections, I expect to see that number increased. If it is not, that’s an indication that there may be a problem, perhaps food, queen, disease, or mite related, and a signal that I need to do a more thorough inspection.

Send your questions to Phil at

phil@philcrafthivecraft.com

www.philcrafthivecraft.com