Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Found in Translation

Teaching Bees New Tricks

By: Jay Evans, USDA Beltsville Bee Lab

Bees have innate (think ‘robo-bee’) and learned (‘show me, sister’) behaviors. Recent work with bees has explored the boundaries of these two forms. While it is dangerous to put our own biases on animal behaviors, the complex behaviors measured seem to include ‘play’, ‘puzzling’ and ‘dancing’. Oh yeah, and they can count as well, even showing an awareness of ‘zero’ things, but that was yesteryear’s news from Scarlett Howard and colleagues (Numerical ordering of zero in honey bees, 2018, Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.aar4975).

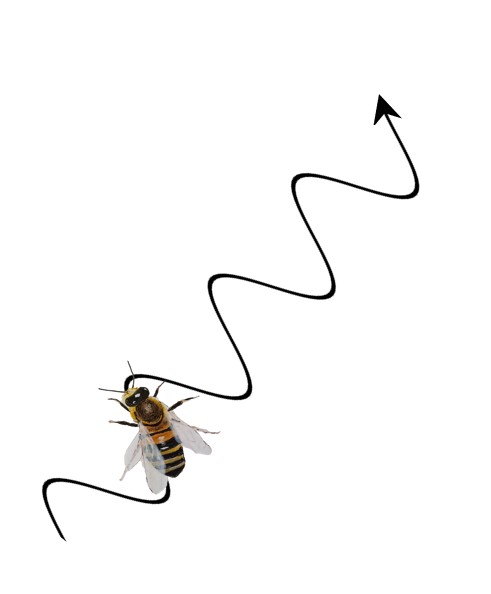

What is fascinating about work coming out just this year is that not only do bees show complex behaviors, but they seem to get better at those behaviors by watching their nestmates. Bee dances will be familiar to most beekeepers and students of animal behavior. Successful foragers often tell their sisters where the good stuff is after finishing their foraging flights. Specifically, foragers signal both direction and distance to flower sources using the waggle dance. True to its name, and shown graphically to the right, this dance involves a bee streaking across the comb and shaking its abdomen for the edification of sister foragers. The angle of this dance on a vertical patch of comb signals the direction of a good food source relative to the current position of the sun relative to the hive. The length of each dance streak provides an estimate of the distance to flower patches (or to sugar baits planted by curious naturalists). By repeatedly dancing, they drum up interest and lead future foragers to a better understanding of how far they might have to fly to get these rewards. The discovery of this dance language is decades old, and justified a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973 for Austrian bee researcher Karl von Frisch. The recent work ups the game by showing that much of this behavior is learned by watching older, more precise, dancers.

What is fascinating about work coming out just this year is that not only do bees show complex behaviors, but they seem to get better at those behaviors by watching their nestmates. Bee dances will be familiar to most beekeepers and students of animal behavior. Successful foragers often tell their sisters where the good stuff is after finishing their foraging flights. Specifically, foragers signal both direction and distance to flower sources using the waggle dance. True to its name, and shown graphically to the right, this dance involves a bee streaking across the comb and shaking its abdomen for the edification of sister foragers. The angle of this dance on a vertical patch of comb signals the direction of a good food source relative to the current position of the sun relative to the hive. The length of each dance streak provides an estimate of the distance to flower patches (or to sugar baits planted by curious naturalists). By repeatedly dancing, they drum up interest and lead future foragers to a better understanding of how far they might have to fly to get these rewards. The discovery of this dance language is decades old, and justified a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973 for Austrian bee researcher Karl von Frisch. The recent work ups the game by showing that much of this behavior is learned by watching older, more precise, dancers.

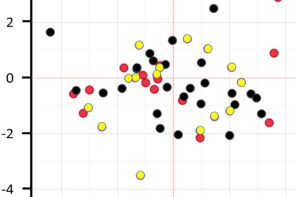

Shihao Dong and colleagues set out to study Social signal learning of the waggle dance in honey bees (2023, Science, DOI:10.1126/science.ade1702). Specifically, they judged the dancing skills of self-starters relative to those of bees that were mentored by older, experienced, dancers. To produce a swarm of naïve dancers, they established colonies comprised solely of like-aged bees, so that all bees reached foraging age together and were therefore less likely to benefit from matching the skills of a senior dancer. Bees from these ‘Animal Farm’ colonies were compared to marked bees of the same age which had grown up gazing at the dances of experienced dancers in colonies with a typical age profile. Naïve bees consistently over-stated the distance they had flown to flowers, in effect telling nestmates to fly right past suitable food sources. They also showed more ‘Dance Disorder’ than both older bees and bees that had been exposed to older dancers. Dance accuracy for all dancers improved over time, it just improved much more quickly when bees had older mentors to watch. So what is the lesson here for beekeepers? No, you can’t force your teenager to watch you dance and expect them to get it, but you CAN see how bees in colonies with an abnormal age structure, thanks to rapid premature death of foragers, might continue to slide by spending unnecessary time looking for food. Long-lived bees are those free of chemical stress, raised with adequate protein nutrition, and arguably bees that have avoided mites and other disease. When you protect your bees from these stresses, just think of how their dance lives will improve.

In a study that, for me, deserved two SMH’s, bees were trained to take on puzzle behaviors, or behaviors that simply don’t present themselves to bees when scientists aren’t around. Working with bumble bees, Alice Bridges and colleagues first taught their bees to open small food boxes by pushing on colored (red or blue) tabs. This a behavior I am not sure I could teach my dog, but she is a bit slow. They then checked to see if bees could follow the lead of a nestmate who had already figured out the box trick. While self-learners emerged in the control colonies sometimes got the knack for opening boxes, bees who observed a nestmate open a box were more likely to successfully mimic that behavior. Over time, bees with a teacher opened more boxes, faster, and were rewarded with more sugar treats. Honey bees and some other bee species are known to spontaneously ‘rob’ flowers by chewing directly into nectar pools when those pools are too deep in the flower for their tongues to reach. It would be neat to see if such nectar robbing is also a learned trait, passed on by adventurous foragers who had to learn the trait the hard way. If so, can such teachers target their lessons to their nestmate sisters?

All of these studies push the known boundaries for bee awareness and behavior, showing all the more how lucky we are to have formed bonds with honey bees and other insects. Clever behavioral scientists will no doubt continue to discover profound, and maybe a bit unsettling, awareness by insects. This awareness is likely to be most evident in the highly social honey bees and bumble bees. What’s next, spelling bees? Stay tuned. In the meantime, get out, find a friend and improve your dancing.