By: Toni Burnham

Free Advice Is Seldom Cheap

There’s an old saying: free advice is seldom cheap, and this column may qualify for that criticism.

I’m not a lawyer, but I frequently get calls about legal issues and beekeeping. I’m also not long on legal principles: it’s not that legal principles are unimportant, just that I am not your source. After 10 years of working to improve the legal status of beekeeping in my home city, and participating in struggles in nearby jurisdictions, I do have observations and advice, however.

When urgent calls seeking help with urban or suburban beekeeping laws come in, they usually take the form of a request for a “model” ordinance or statute: an example of what a bee law looks like in places that have them. The folks who ask often end up as disappointed as newbees who question a seasoned beekeeper what something they see in their hives. Why? Because the answer is almost always “it depends.” There are all sorts of laws, all sorts of differences, all sorts of outcomes.

There isn’t a one size fits all model, though there are places beekeepers have gotten a better deal than others. One reason we receive these calls and emails is that beekeeping was more widely legalized here in DC only a couple of years ago, and we got a pretty decent law and a set of livable institutional relationships. Other cities have achieved legalization, but their beekeepers consider themselves on shakier ground. Some lucky urban apiculturalists operate in places where beekeeping always seemed to be legal, and where they feel little threat.

So, to give you good advice, just like a colony management decision, you need to be able to share a whole bunch of history, what the most common problem is today, and what you are shooting for in future.

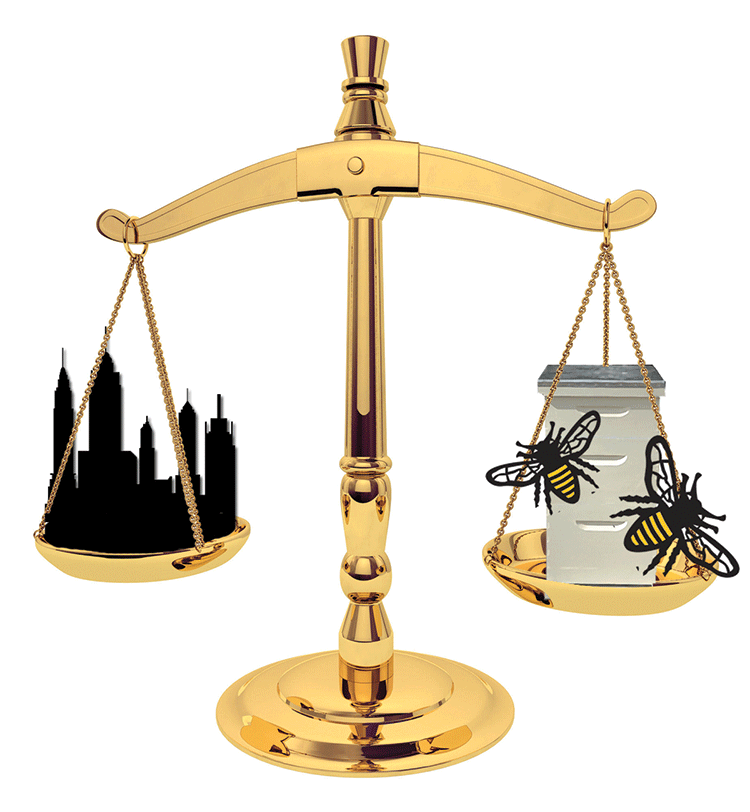

From our experience, struggles to ensure the legality of city beekeeping can be divided into three categories: creating legal protections where there are none; overturning outright bans; and blocking efforts to ban beekeeping. This work also takes place at different levels on different occasions: state, county or city; neighborhood or home owners association; or even within any of a dizzying array of regulatory bodies (zoning, departments of health, animal control, police, etc.) The reason to consider all this complexity is this: if beekeeping has been made illegal, or someone wants it to be, you need to know what problem triggered these events, who had it, and at what level it took place. Target your approach on the problem that arose and the outcome you want, and get there by resolving conflicts, rather than creating them, if at all possible.

If you are trying to make beekeeping legal in a place where it hasn’t been, you need to know what kind of law banned it (Zoning? Public safety?) and how best to persuade exactly the right people to change their mind – without triggering an organized opposition. If there are no laws on the books, but your community is growing and needs rules and protections, try to identify the regulatory agency whose goals align most closely with yours (Environmental Protection or Public Safety? Animal Control or Department of Health?) and consult with them. If at all possible, meet with someone in a position of real responsibility and power and become allies. If you ask just anyone who answers the phone or whoever takes the current shift at reception, they probably won’t know who to talk to if you don’t, and it is easier to tell you “no” and get you to leave than to work on finding you a better answer.

If opposition and suppression of beekeeping is brewing, who are your community and political allies? What is getting people upset? Who would benefit from a beekeeper endorsement?

And some more advice upfront: if your beekeeping community thrives on the idea that it is saintly or special, egocentric or edgy (or worthy of celebrity status), you are undercutting its welfare. I can’t think why a community would want to welcome dozens of eccentric individualists packing tens of thousands of stinging insects, each. Folks who look like ordinary, responsible neighbors, though – people who you expect to see around – seem both to belong and enrich the life of a neighborhood. Your legalization efforts are more likely to succeed as a natural outgrowth of community life than as a crusade from outside it.

More general pointers: identify all the tools available to you, not just the fiery, flashy ones. Bees are the great connectors in nature, they link plants to people, and they can connect us to our communities. Ongoing outreach that makes bees familiar and desirable, continuing beekeeper education and promotion of best practices, open channels of communication and reliable networks with community institutions and leaders, services like swarm catching and insect identification, and then public appeals and press coverage all help protect your right to keep bees. It’s better to ask for a meeting and offer to help solve a problem than to embarrass the person from whom you want help.

Overturning a ban

The legal story in DC was about overturning a ban, with a goal of creating new protections. Our old law was nonsensical and unenforced, with no city department wanting to be stuck holding the bag. An unloved law with no advocates is one ripe for change, and no one had created a reason to fear beekeeping through a public stinging incident or injury.

What we wanted was something similar to the law in several surrounding jurisdictions: please note, this kind of harmonization of statutes is often a powerful argument for economic as well as legal reasons, and politicians often take notice. In Northern Virginia, the beekeepers in a nearby county toiled to get beekeeping legalized, and succeeded with requirements that were entirely reasonable and similar to those in other jurisdictions that border us. We could point to them and say, “Hey! Look at that!” We were also in the lucky position of having an embarrassing law while being surrounded on all sides with good examples: people were motivated to change with a clear signpost in the right direction!

DC is a divided city, however (no surprise there!) Bees are pretty firmly associated with “green” issues such as environmental protection and urban agriculture. In this town, those issues are also code for middle- or upper-class, and gentrification rather than community building. People from other demographic backgrounds have been less represented in beekeeping, composting, community gardening, and so on in part for historical reasons, too. In this region, many working class people are only a handful of generations removed from subsistence farming, even sharecropping, and the move to a city and to office or retail work was a gigantic step upward in political, economic and physical well being. Those “crazy” new arrivals who raise the cost of housing and then want to turn lots into farms, and then think it’s a great idea to get kids to dig around in the dirt again are imagining a very different idea of progress than that of folks who were happy to lose their calluses.

There was therefore a potential opposition, a different vision of what urban spaces should be like, that we could create if we indulged in attitude and an attempt to impose our own opinions. There was also an opportunity to undermine potential conflict by working under the radar, making relationships and providing support to the community in a way that made us familiar and valuable. In fact, we probably played around with forming these relationships (with the public schools, parks and university, with the police, with the city arborists, with churches and community gardens and so on) longer than we had to. By the time someone had the gumption to ask the City Council to change our law to something very supportive, it passed with a unanimous yawn. We also have good relationships and ongoing collaborative conversations with city regulators, and they continue to listen to us.

Preventing a ban

In our suburbs, similar conflicting visions of how densely populated spaces should be used has also had an impact on legal beekeeping. I have received calls from Virginia and Alabama, Pennsylvania and Maryland, often as a product of changing populations and development. Across North America, fields that once grew crops are sprouting developments, and the community covenants that accompany the latter may be a bigger threat to beekeeping than any urban zoning rule. In many (if not most) jurisdictions, honey bees are classified as livestock, and new residential neighborhoods specifically ban the latter, or place hugely restrictive lot size and setback requirements in place. These effectively place beekeeping out of reach for the majority in these communities.

Two counties in Maryland have faced this in recent years, with differing processes but similar results. A more rural, northern county was faced with a nuisance situation created by a beekeeper who was, essentially, a jerk who would have harmed nobody else if he lived on a farm, but his home was in a subdivision. His neighbors went to local government, livestock laws in hand, the beekeeping community showed up with assistance in remedying the nuisance. Because leaders out that way could speak with reasonable beekeepers, were not publicly shamed in the press, and did not wish to take on a whole new police and regulatory activity, the issue was settled, at least for a while.

What used to be a rural beeyard may suddenly be an urban beeyard. Proactive regulations will prevent restrictions or removal, but insure the safety of the new residents.

In another case, a county much further down the road in converting farms to tract mansions took a different stand, enforcing huge setback requirements. In this case, two neighbors, once a beekeeper, had very different notions of what belonged in their community, what constituted a threat, and even the effect that keeping bees could have on nearby home values! (Perhaps one suggestion this column could make is this: Never get on the wrong side of a realtor.) The local beekeeping community had to stage a long, hard, public, and complicated fight to re-write the rules: at great expense in time and money, and with no guarantee of success. While beekeeping was protected, ongoing enmities were created: a victory with a cost.

And the rumbles continue. A county to our East, where beekeeping has always been legal by right, is considering a zoning rewrite where bees could be banned. To our northwest, this nearly happened when a consultant for a long-overdue zoning revision slapped in boilerplate language that banned bees. Many long time beekeepers were angry and outraged, but members of the local beekeeping club (from many different political persuasions!) banded together, made appointments to speak with the officials engaged in the revision, politely shared information, regularly attended meetings as the process rolled out, and ended up protected. Had the club gone directly to direct opposition and public outcry (tools that we all should have and use if necessary) they would have missed the chance to inform the process. There is also some hope that the consultant involved has learned a thing or two!

Creating protections

Finally, it may seem like real madness to engage the lawmaking process when no one is bothering you, but I want  to share with you the situations that can seem to suddenly overtake your beekeeping community, and to give you advance warning. The call we received from Alabama recently involved a community in the process of getting denser and richer, with a bona-fide golf course on the way. With new people and new houses came new proposals for limiting agricultural activities, including beekeeping. It is much harder for amateur beekeepers to confront a multi-million dollar development plan than it is to craft agreements with people they know in a community that is familiar for a future in which they can keep bees. I frequently look at changes in land use in the areas around DC, and beekeepers that consider themselves safe today will certainly face challenges in the future. This is not only true here: the population of Medina County, where Bee Culture is published, has grown 25% in 20 years. Editor Kim Flottum tells a story about a Medina beekeeper with hives that were once out in the country. He didn’t move, but cars and houses moved closer, including the lot for an auto dealership. Fecal trails from the bees, which used to fall on fields, kept ruining new car finishes. The beekeeper closed down his operation: it cost too much to deal with the damage. and he had no legal protection.

to share with you the situations that can seem to suddenly overtake your beekeeping community, and to give you advance warning. The call we received from Alabama recently involved a community in the process of getting denser and richer, with a bona-fide golf course on the way. With new people and new houses came new proposals for limiting agricultural activities, including beekeeping. It is much harder for amateur beekeepers to confront a multi-million dollar development plan than it is to craft agreements with people they know in a community that is familiar for a future in which they can keep bees. I frequently look at changes in land use in the areas around DC, and beekeepers that consider themselves safe today will certainly face challenges in the future. This is not only true here: the population of Medina County, where Bee Culture is published, has grown 25% in 20 years. Editor Kim Flottum tells a story about a Medina beekeeper with hives that were once out in the country. He didn’t move, but cars and houses moved closer, including the lot for an auto dealership. Fecal trails from the bees, which used to fall on fields, kept ruining new car finishes. The beekeeper closed down his operation: it cost too much to deal with the damage. and he had no legal protection.

In the end, laws are agreements that communities forge among their members, and beekeepers are valuable members of these precious communities. We can influence these laws without being lawyers or politicians, but by being participants in the community and guardians of beekeeping’s role in the latter. To me, this activity is more like gardening than warfare, more like networking than outrage. If there is a problem facing legal beekeeping in your city, learn about the nature and location of that problem and find a way to help resolve it. Don’t wait for a crisis to protect something you love, and be listening for legal changes that could affect your bees. Don’t create a crisis instead of a solution. Be part of the community and conversation around legal problems, and be ready to ask for the outcome you and your bees deserve.

Toni Burnham keeps her bees in Washington, DC and keeps up with what’s going on in urban beekeeping.