By Toni Burnham

The Golden Years Are Gone.

The most experienced beekeepers I know tell me of golden years some three decades ago, before Varroa made its landfall in Florida in the 1980s. My friend Ken once said, “It was almost as if you could just throw some bees in some boxes behind the barn, then just grab the honey come August.” Then it got harder. A lot harder.

A lot of beeks like Ken threw up their hands in those days–they hadn’t signed up to kill bees, after all–and the numbers of sideliners declined. Urban beekeeping is one of the reasons that the number of beekeepers may be rising again, but it seems that may present some challenges in the city, too.

If I were a new beekeeper facing some of today’s hurdles, I might soon be in the bleachers with Ken. You can actually get to blue skies from here, now, though.

There is absolutely no question that I’ve been lucky, both when and where I started (though my bees have taken a bunch of shots along the way). My first bees overlapped mostly with feral colonies, since beekeeping hadn’t become hip yet, and the mites weren’t packing the horrid viral cocktail they are serving now. There were simply no Small Hive Beetles. Only one Nosema. There’s a colony on my roof that has wintered every year since 2005/6, and it has produced glorious healthy bees, honey and the occasional swarm right up until now.

But it’s not because of me. Things I have done wrong: feeding 2:1 at below freezing temperatures, leaving a honey super on the porch in August (“It was just a few minutes!”), storing (unfrozen) brood boxes in a dark basement, procrastinating until October for mite tests and treatments, failing to secure the upper entrance while moving a hive (down a spiral staircase!) . . . oh, the comedy goes on and on. You can learn how to fix a wide range of emergencies when you trigger a lot of them.

Bottom line: my bees survived because the urban world around them was a more forgiving place.

A few years of skill-building before facing the deluge has mattered for the long term. When I took a September mite count for the 2018 Mite-a-Thon, it was 2/100 even with brood in two deeps and a medium, the way they have been running all summer. I’ve split it, twice. Did I mention the 3.5 supers of honey?

When I look at my wonder hive and my haphazard management, I wonder why it has been so difficult, in recent years, to help many of the new beekeepers here to get to this place I call “Cruising Velocity.”

What is this “Cruising Velocity?!”

To me, this means a state of equilibrium where the city bees have become well-adapted to the place they live: adjusting their populations in synch with local seasons and signals, foraging well, splitting every Spring, managing mites and beetles without much help, needing feeding support only occasionally, being polite neighbors.

The cool thing about this Zen state of beeing is that the interventions the bees need are not huge/emergency/high stakes/life-or-death magnitude events.

Big interventions, even when desperately needed, are high risk/high reward, and nature prepares critters for more normal stuff. Nature’s favorite number is “average:” average temperatures, average rainfall, average colony size, average forage availability. Everything has evolved to know what to do with what usually happens. It’s the outlier events that test the odds.

Those super successful bees on my roof have (mostly) got this, and if I maintain a modest glimmer of a clue (the best I can muster some days), I’m there when they need me, and not as a superhero.

But our urban newbees have no reason to believe they will encounter luck like mine. It is luck, too: my major contribution to local beekeeping has been to make every error or succumb to every bad idea. Until the next one.

Why is it harder to get to equilibrium?

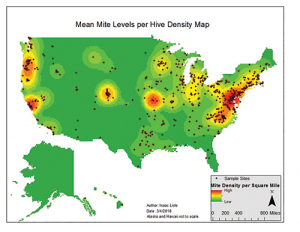

This map is based ont the number of reporting locations from 2017’s first-ever survey program, so many areas (especially in the west) may look light on mites when there were really just no participants. But there were LOTS of reports where I live, and the story was sobering.

It’s especially harder for folks here who have started in the past five years to get to Cruising Velocity, I think. Beekeepers are now thick on the rooftops (and the community gardens, and the campuses, and every patch of urban greenspace they can find). We have nearly 500 registered hives in the 68 1/3 square miles of Washington DC today (I could find only a dozen or so in 2005).

This means that newly established urban honey bee colonies will be exposed to every existing threat without exception, just because there will inevitably be a hive within foraging distance which is succumbing already. We also bring in bees constantly to meet growth that outstrips the capacity of our relatively new local nuc producers, and to replace high losses. That’s a potential conveyor belt carrying pests and pathogens from other regions to our doorstep on a regular basis, too.

This is not because someone is awful or at fault: it is the odds.

It works like this: do you know the rule of thumb that only one out of four uncaptured swarms survive to establish a new colony? How would you do this math?

If you have 100 other honey bee colonies within flying distance of your apiary, all have been exposed and some significant number are weak from a Varroa vectored illness. Some are also weak because a queen is in decline and perhaps Small Hive Beetles are finding a way in (I’ve had this happen while a decent colony was just requeening). Some of your neighbor colonies have inevitably robbed a hive that dwindled away due to Nosema; some are competing for dearth-time forage in places so crowded with bees that pests can practically jump from thorax to thorax. Those dearth periods may have effectively gotten a whole lot worse when (no exaggeration) ten times as many colonies are competing for the resources to survive a few critical weeks, so nutrition ain’t great.

“OK, prove it.”

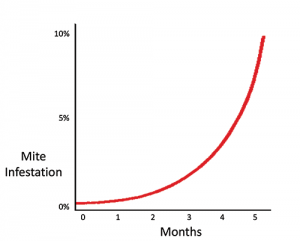

Many of our new beekeepers here tell me, at some point, that none of this could be true for their bees. For example, they have never “seen” a mite on a bee. After I finish slapping my forehead, I like to show them one of the graphics from the Honey Bee Health Coalition:

I

f you have an urban colony with a near-zero level of Varroa mite infestation, your bees will not stay clean forever. According to work by Meghan Milbrath at MSU Extension, if you have even one mother mite in your colony, she is capable of exponential growth that can put you at 12,000-14,000 mites within 10 brood cycles. In your city, there is a mother mite somewhere, with her legs extended on top of a flower in a patch of high-demand dearth-time forage, just waiting for her ride back to your place.

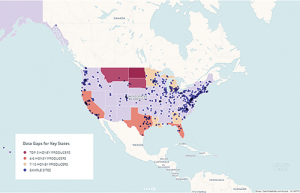

As part of the annual Mite-A-Thon (now in its second year), The Pollinator Partnership has also shared a recap graphic from last year’s survey. Here, you can see that the place where I live is a potential red-hot zone for varroa mite density.

This map is based the number of reporting locations from 2017s first-ever survey program, so many areas (especially in the West) may look light on mites when there were really just no participants. But there were LOTS of reports where I live, and the story was sobering.

The path to blue skies

A Master Beekeeper once told me that the recipe for successful beekeeping is this: a good class, a good mentor, and a good community. Many urbanites like me live around a lot of people but starve for that kind of community.

Well, that will starve your bees, too: join a club, take their course, work with people who have been doing this–in your area–for a while. Even if you are shy. Even if you are the smartest person you ever met. Even if the bees you have purchased were promised to be pure as the driven snow and immortal.

The best start you can get for the bees is a local nuc, too, but you can get to strength even if you start with a shipped-in package. We have been experimenting with Oxalic acid vaporization on incoming packages and supporting just about anyone who is willing to graft queens from overwintered local stock. This is meant to knock down loads, then get a healthy new colony ready to take a readily-available, well-mated local queen.

And requeen that package. Just do it. Pinching your first queen (who may not yet have done anything wrong) seems like a heartlessly cruel thing, counter to your goal of raising rather than killing bees (I still cry inside when I do it). But every single bee in that colony would take one for the team, and they are not averse to making new mommies on their own, either.

Buy one of the increasingly easy to use mite testing kits and learn to use it as soon as you have a couple of frames of capped and some mixed brood. Go ahead and do a small (less than 300 bee) sample if you are worried about losing too many bees too soon. Write down your result. Do it again after another brood cycle (21 days, plus or minus). Use an alcohol wash if you have become as worried as I am, do a sugar shake if you can’t bring yourself to kill the sampled bees (but do it really, REALLY, well). Go to the Honey Bee Health Coalition website (http://honeybeehealthcoalition.org) and grab a copy of their mite threshold matrix to analyze your results. After you have done this a bunch, you get a tremendous eye for what looks right (or wrong) even before you pop the top of a hive.

If you spot your problems early, even if you have not gotten to a truly established colony yet, you can still do easier, less risky interventions.

And ask for help: this is just a lot to learn, and I am still learning shamefully basic things every year. Almost all of us will help you newbees if we can and you are trying hard, too. I’d love to think that there are more of us up on our roofs, drinking morning coffee and watching the first pollen packs of the morning fly in.

What Is the Mite-A-Thon?

In 2017, The Pollinator Partnership, the BeeInformed Partnership, and an impressive number of partner organizations from across the commercial and academic bee worlds launched the Mite-A-Thon, an effort to collect mite infestation data and to visualize Varroa infestations in honey bee colonies across North America within a one-week window each year. The idea is that beekeepers will become more aware about infestations and better able to monitor and address them. Later, the partners will make management strategies available for discussion within bee organizations using information and outreach materials they develop.

It’s easy for individual beekeepers to participate: do a Varroa mite sampling test during the annual sampling period (a week in September), then go to www.mitecheck.com and report your results (mites per hundred and apiary location). You can see graphics displaying survey information as it comes in!

In 2018, the Mite-A-Thon provided recap data for the previous year that compared mite densities among reporting locations, giving beekeepers an idea of infestation levels they might confront in the areas where significant numbers of beekeepers participated in the survey.

Toni Burnham keeps bees and helps new beekeepers get started in the DC area.