By: Joseph Cazier, Walter Haefeker, James Wilkes, Edgar Hassler

For Commercial Beekeepers.

Introduction

In last month’s Bee Culture article, “Data Sharing Risks and Rewards for Hobbyist Beekeepers,” we explored the risks and rewards of sharing data for hobbyist beekeepers who have a limited financial stake in keeping bees. This month we focus on the risks and rewards of data sharing for large sideliners and commercial beekeepers who do receive a significant portion of their income from their beekeeping operations (for simplicity, we will treat sideliners as part of the commercial group of beekeepers). The addition of financial incentives and the size and complexity of commercial operations adds another dimension to the risk/reward calculation, which we explore below.

First, we will provide a quick look at the current state of computing technology in commercial beekeeping operations and discuss reasons why commercial operations should be treated differently than hobbyist when it comes to data sharing, then we will review a few key points from the last article and discuss how these complications impact the risk reward calculation. Next month, we plan to follow up with trust-enhancing policy measures that could be used to address some of these risks and incentives and then explore how advances in technology and proper system architecture can also change the dynamics.

Commercial vs Hobbyist Beekeepers

The number of managed hives varies considerably for commercial beekeeping operations around the world, from a few hundred to tens of thousands. Regardless of the number of hives, the commercial beekeeper faces a variety of challenges to running a successful business that extends well beyond keeping bees healthy, though healthy bees certainly make the rest of the challenges easier to overcome and may provide a generous margin for error.

As the number of hives increases, the number of yard locations increases; the number of personnel required to manage those yards increases; and the amount of hive hardware, vehicles, support infrastructure, extraction equipment, sales and marketing staff, etc., also increases. This is typical of any industry as production scales and, similarly, as record keeping requirements scale for long term business success. One can assume commercial beekeeping operations keep records, but how much of it is digital or integrated across the operation?

Historically, the adoption and use of computing technology within the bee industry is fairly low and acceptance of new technologies is slow, lagging other sectors of agriculture where ag tech is having success. There are notable exceptions with multiple attempts by commercial operations to develop in-house solutions as well as external investors buying beekeeping operations with expectations of technology playing a role as it does in other business sectors. In addition, there is a noticeable generational shift occurring in many family-based businesses with the younger generation taking over operational decisions and consequently being more open to technology.

However, bringing technology into the commercial beekeeping landscape is difficult for a variety of reasons that are worth exploring in a future article. Even seemingly simple digital record keeping like yard locations, hive counts, and management actions present difficulties and can pose significant risks to the beekeeping operation. For example, yard locations are one of the most valuable assets for a commercial beekeeper and must be protected from both external and internal threats.

As noted already, as the scale of an operation increases, the internal need for good record keeping not only as it relates to hive tracking, but also as it relates to equipment, supplies, workers as well as products and customers, increases as well. What may be a “nice to have“ at the hobbyist level becomes essential for a well run professional operation, and, as stated above, while still in the infancy stages, digital record keeping will be the key to running all aspects of an enterprise more efficiently in the future (see our May 2018 Bee Culture Article – Electronic Records – A Path to Better Beekeeping).

The scale of the operation affects not only the internal data requirements for running a business, but also increases the need to provide data externally to comply with hive registration requirements, complete government and non-profit surveys, document the fulfillment of pollination contracts, identify best practices, manage employees and more. See this article by Jamie Ellis for more information on beekeeping regulations1.

In addition to the regulatory and business concerns, the internal data of large commercial operations are much more interesting to competitors than those of a few hobbyists in the neighborhood (though recall this hobbyist data is still very important from the perspective of building a Genius Hive). For example, the digitization of a commercial beekeeping operation leads to the generation of large amounts of data, which inevitably will be of interest to a variety of third parties. The information contained in these data sets can have significant commercial consequences that would not be of concern to a small scale hobbyist.

This brings the concepts of competitive advantage, trade secrets, and business continuity to the forefront when thinking about commercial beekeeping data. This is also why the HiveTracks.com commercial software (See Figure 1) is very different from the HiveTracks.com hobbyist software – having a focus on workflow management and business continuity – with each operational instance having some customizable features and heightened privacy awareness and protections.

For commercial beekeepers, it is essential to stay in control of the data of their business and anybody designing solutions for managing and sharing those data needs to ensure that the information is well protected but can be shared in a carefully controlled manner when it is of mutual benefit to do so. If commercial beekeepers have no confidence in the data integrity of such systems, they will not use them and will miss out on the major benefits.

Poor confidence in data protection can also lead to the classic bad situation of “two sets of books” being kept. This is not ideal for the beekeepers, regulators, or others who need accurate data to make better decisions. In many cases, this situation can even lead to false or misleading data being provided by the beekeeper in order to protect his/her interests. Since having false or misleading data is generally worse that having no data at all, it is essential that any system built for commercial beekeepers be specifically tailored to them.

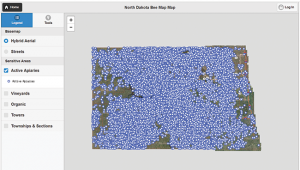

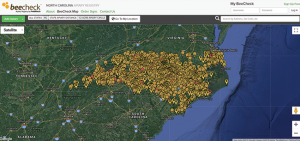

A cursory examination of a few existing honey bee data collection systems, both private sector/non-profit (Field Watch/BeeCheck) and government operated (North Dakota Department of Agriculture), which mostly revolve around yard locations, reveals that participating in these systems presents an inherent risk to the beekeeper because yard locations are now in the possession of a third party and, in some cases, are even exposed to public view, as in the North Dakota Bee Map in Figure 2 and the BeeCheck Map in Figure 3.

- Figure 2. Publicly accessible beeyard map for North Dakota. Each blue dot is a beeyard with beekeeper contact information available by hovering over dot. https://beemap.ndda.nd.gov/map.

- Figure 3.Publicly accessible beeyard map for North Carolina. Each pin is a beeyard with beekeeper contact information available by clicking on pin https://nc.beecheck.org/map

While the intentions of both of these systems are good for beekeepers, at the same time, it clearly elevates their risk with a public display of yard locations. This privacy exposure also opens up and magnifies the additional risk of hive theft and vandalism. This risk is not only to the beekeeper, but to the farmers who depend on them for pollination service. This situation is especially true since it is often precisely during the pollination season when hives might become most valuable to a thief looking to make some quick cash off of the stolen hives.

Another very recent example that bears close scrutiny due to the civil penalties/risk associated with not sharing information is the California program Bee Where2 which gives agricultural commissioners’ the authority to level fines to beekeepers who do not register and keep up-to-date records of their hive locations.

In light of the rest of this article, which quantifies the level of risk of sharing data and the examples where data is shared, the challenge becomes this: how do we navigate to a new ecosystem that has privacy protections in place? How do we record and share yard locations in a way that shares useful information but does not not hurt the competitive advantage of the commercial beekeeper?

To complete this analysis, let’s first complete our review of some of the key concepts of privacy risk from the last article, add a few more to address commercial beekeepers, and then analyze their impact on data sharing.

Review

We began last month’s article with a discussion of Risk Theory which breaks the risk a beekeeper faces, including that of sharing information, into two important subcomponents. These are:

• Risk Likelihood (RL): This is the probability or likelihood that someone’s privacy will be violated.

• Risk Harm (RH): This is the level of damage that could occur in the event of a privacy breach.

By looking at these components separately, it is easier to judge the seriousness of a given threat and make sound business decisions based on that risk. Beekeepers can judge the risk of something occurring and perhaps assign a probability score (such as 30% likelihood of contracting Varroa in this hive this year). They can then also assign a damage weighting on some useful scale (such as one to 10) to weight the severity of the risk (such as 10 for AFB). They then can multiply the two scores together (i.e. 30% probability of Varroa X 6 Severity) to get a score they can use to make management decisions by ranking all of the risks and deciding the appropriate courses of action to manage those risk in a thoughtful deliberate way.

In the next sections, we look at what some of these risks might be, and we will try to break them into these two components for analysis and discussion.

Information Sharing Risks

In the last article, we discussed several risks that a beekeeper could face due to information sharing. These were:

• Reputational Risk: A loss of reputation among friends, a small group, a private company, or a non-profit organization

• Compliance Risk: Risk of fines or punishment if doing something not permissible by the government (avoiding fees, taxes, registration or using off label treatment)

• Regulatory Risk: Risk of government interceding in the beekeeping operation in a way that the beekeeper would perceive as unwelcome, unnecessary, without cause, or for dubious reasons, or not interceding when needed.

Commercial beekeepers face these risks as well as a few more. These include:

• Loss of Competitive Advantage: Trade Secrets often help a business maintain an advantage over other similar businesses. This advantage is often referred to as a competitive advantage as it generally helps them earn higher profits. While trade secrets are not the only source of competitive advantage, it is nevertheless an important one.

• Legal Risk: As a larger scale actor, commercial beekeepers face larger scale risks than hobbyist beekeepers. If they fail to perform on a contract, deliver the agreed upon product, cause some real or perceived harm or have an employment dispute, they can face real legal risks. Having good data can either protect them by showing innocence or compliance, or hurt them if they are at fault.

• Financial Loss: Commercial beekeepers by definition depend on their bees for their livelihood. Thus any loss to their operation impacts them much greater than a hobbyist.

• Business Continuity: Commercial beekeepers must have the right data to run their operation effectively. If the data does not measure the right things, is incomplete or inaccurate, beekeepers can suffer a loss in their business by making poor management decisions.

After a risk is identified, there is a strong tendency of assigning a low likelihood to it in order to avoid the effort of eliminating it completely. But, according to Murphy’s Law, “Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.” A larger scale operation will have a higher likelihood that something will go wrong because the dice get rolled a lot more often. A large dataset is also very attractive to other actors, who may not have the best interest of the beekeeper at heart. Therefore, it is very important to accurately assess and eliminate or manage any identified risk.

In the next section, we will explore each of these risks for commercial/sidliner beekeepers and extrapolate the incentives they have to share (or not share) accurate (or misleading) information. Again, in the next article, we plan to focus on how good system design, new technologies, and better policies can help address these risks at the system level, reducing or eliminating them on the front end.

Risk Analysis

Keeping Records for Yourself

Much like hobbyist beekeepers, risks associated with internal record keeping may be relatively low when proper controls are in place. The determining factors are the breadth of dissemination within the organization and the ease with which unauthorized individuals may access the data. Another contributing factor may include whether the organization is attempting to conceal nefarious activities – a factor that would significantly increase both the likelihood and degree of harm the organization may suffer.

For our purposes in this article, we will assume proper controls are in place and the organization is devoid of nefarious activities.

• Reputational Risk: The Privacy Risk Harm and Risk Likelihood to this type of data keeping is relatively low. If controls fail, the likelihood and degree of harm become equivalent to sharing within a group comparable in size to the extent to which the data are shared. Even in the event that the likelihood of a risk was high, the harm would likely be low.

• Compliance Risk: Similar to hobbyists, the risk of sanctions are low for keeping your own records. It is possible that if there is a problem, the court may subpoena the records and use them as evidence in a case; it is also likely the records could be used to exonerate the organization, therefore it may be a wash. While the risk of a compliance event happening is very low in this scenario, the harm could be quite high.

• Regulatory Risk: The Privacy Risk Harm and Risk Likelihood to this type of data keeping is low with the primary risks being poor external or internal governance based on incomplete information. The likelihood of this risk is generally quite low, but it captures the imagination as the harm could be quite high.

• Loss of Competitive Advantage: The risk in this happening is moderate, but, paradoxically, it may be necessary to keep data in order to develop a competitive advantage. However, if it does happen, it would reduce real income, making it reasonably high in severity.

• Legal Risk: The Privacy Risk Harm and Risk Likelihood to this type of data keeping may actually come from not keeping data. Failure to report required information to authorities can lead to legal jeopardy and an inability to defend the organization. Good records may actually lower the severity of this risk while also reducing the likelihood.

• Business Continuity: The Privacy Risk Harm and Risk Likelihood to this type of data keeping is low. In fact, it can enhance decision making and profitability of the overall organization.

• Financial Loss: Financial loss related to this type of data keeping is low but may increase due to loss of reputation or competitive advantage. That said, anyone depending on beekeeping for their income would be very mindful of this risk, from whatever source.

Sharing Summary Information

If this data is shared anonymously, much of the risks are greatly reduced, which is why many surveys ask for data anonymously. However, the ability to check the reliability of the data also disappears. Additionally, much of the potential value is lost, such as the ability to find secondary causes of an event – weather, overspray, genetic susceptibility etc. It also minimizes the ability to aggregate a controlled sample enough to build a real predictive model useful for decision support. Therefore, for this analysis, we will assume that the information is accurate and identifiable.

• Reputational Risk: There are both reputational risks and rewards for sharing summary information with an organization, depending on how the operation performed and how much the beekeeper cares what others think.

• Compliance Risk: There is a medium level of risk that if beekeepers are not doing something they are supposed to be doing they could be caught with summary data. This risk is reduced by being diligent in complying with any relevant rules and regulations.

• Regulatory Risk: Sharing good summary information may help or hurt with regulation. On the one hand, regulators may see good summary information and assume your operation is complying and leave you alone; alternatively, they could see a problem and come to help in a way you are not excited about.

• Loss of Competitive Advantage: A competitor may notice how well you are doing and study your operation for ways to better compete and potentially copy your competitive advantage. However, you might also get ideas from others and all do better.

• Legal Risk: Summary information shared with a contract partner, such as for pollination services, may be required by a contract. Good data can help mitigate risks, especially later as crops grow and there is good documentation of services provided. However, if they do not match observations, there could be some trouble.

• Business Continuity: This is the risk that includes, but is not limited to, some of the other risks. If any of the other impacts are large enough they could force a beekeeper out of business. Note that this could include poor management decisions stemming from not keeping good records.

• Financial Loss: Depending on the regulatory environment, not sharing accurate data could lead to fines or other financial losses, as noted in the case of the Bee Where program in California, discussed above.

Sharing Detailed Data

The risks of sharing detailed data largely depend on who you are sharing them with, and is much more risky for commercial operators whose livelihood is at risk. As the risk profile is similar to that of summary data, but more intense, we will defer a point-by-point analysis. However, note that generally the more detailed the data, the greater the risk, but also, in the age of data science, the greater the potential benefit.

Most commercial operations would not share detailed data with anyone, including a government, without real protections. Yet with the tools that data science has to offer, such detailed information can be used to help and guide these operations in ways that were not available before. Summary data is not sufficient for this type of analysis and support. But there are ways to protect the identity of the user and still get the detail needed for beneficial analysis and application.

It is specifically for the reasons mentioned above that commercial beekeepers need their own software system, with system-designed controls to mitigate privacy risk harm and likelihood. This action should be done in a way that can still benefit operations and those of other beekeepers in a risk-mitigated way, so all can capture the shared benefit while preserving bees and our food supply.

Conclusion

The key is in aligning the incentives. In general, beekeepers love bees and want them to do well, they are too important not to protect. The key is in aligning the incentives correctly to protect what needs to be protected while learning what needs to be learned to help beekeeping operations thrive. By building a system and adjusting policies in a way that manages these risks correctly, we can together build a system that works for everyone. This will be the subject of our next article.

Finally, special thanks to Project Apis m. for supporting a portion of this work with a Healthy Hives 2020 grant, to leaders at HiveTracks.com for sharing their thoughts on this topic and to the editors of Bee Culture for publishing this work. These efforts would not have been possible without visionary groups like this one providing support and resources.

1https://americanbeejournal.com/beekeeping-rules-regulations/

2https://www.westernfarmpress.com/print/46367

Joseph Cazier, Ph.D is the Chief Analytics Officer for HiveTracks.com and Executive Director of the Center for Analytics Research and Education at Appalachian State University. You can reach him at joseph@hivetracks.com

Walter Haefeker is a professional beekeeper from Upper Bavaria, board member of the German Professional Beekeepers Association, as well as President of the European Professional Beekeepers Association.

James Wilkes, Ph.D is the founder of HiveTracks.com, Computer Science Professor and Sideline Beekeeper.

Edgar Hassler, Ph.D is the Associate Director for Technology at the Center for Analytics Research and Education at Appalachian State University. You can reach him at hassleree@appstate.edu