- Movement of Pesticides into Flowers, Nectar and Pollen

- Patterns of Pesticide Use Affect Pollinators

- Beekeeping Business Uses Every Bit of the Bees, the Land and the USDA

Alan Harman

University of California, Riverside researchers have developed a new type of solid-phase microextraction (SPME) probe that inserted into plants through a needle, allows repeated sampling of seven neonicotinoids in plant sap.

SPME probes use a fiber coated with a liquid or solid to quickly extract analytes from a sample.

The method by Jay Gan, chair of the Department of Environmental Sciences and colleagues, is a simpler, more direct way to monitor neonicotinoids in living plants that captures spatial and temporal movement of the insecticides.

It was demonstrated in lettuce and soybean plants, with each sampling taking only 20 minutes. The analytes were then recovered from the probe and analyzed.

This procedure allowed the researchers to quantify neonicotinoids in plants and study their movement and distribution throughout the plants over time.

The method could be used to monitor movement of pesticides into flowers, nectar and pollen to pinpoint where and when maximal pesticide exposure occurs for bees and other pollinators, the researchers note.

Neonicotinoids are water-soluble insecticides that are applied to seeds or foliage. But non-target organisms such as pollinating bees can also be exposed to the substances, mainly through residues in nectar and pollen of flowering plants, which bees use to make honey.

Most studies to-date have relied on correlating the presence of neonicotinoid residues in plant samples with bee declines. A few studies have measured total neonicotinoids in plants but laborious methods were used.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

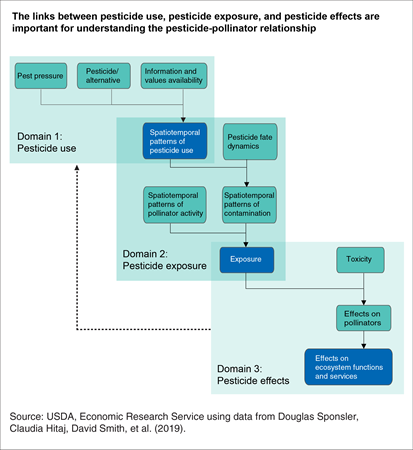

Pollinators such as honey bees, wild bees, and pollen wasps contribute to one-third of the world’s food-crop production. However, the health and abundance of pollinators has declined in recent decades due to a range of factors that include pests, pathogens, pesticides, and poor nutrition. Farmers use pesticides to treat pests that would otherwise damage our food. Patterns, or “domains,” of pesticide use and pesticide effects on pollinators are linked in a complex system through a third domain, pollinator pesticide exposure. This framework can provide insights into options for reducing risks to pollinators while also improving pest management strategies for crops, as illustrated through the example of apple production.

Farmers’ patterns of pesticide use depend mainly on pest pressure, the availability of pesticides, and farmer information and values. Agricultural pests are a continuous threat because new pests emerge (e.g., brown marmorated stink bug), existing pests become resistant to pesticides (e.g., rosy apple aphid), and pesticides found to be harmful are restricted (e.g., some broad-spectrum insecticides used in apple orchards). This creates demand for the development of new pest-management methods, including novel pesticide chemistries (e.g., neonicotinoids).

Understanding pollinator pesticide exposure requires linking pollinator activity patterns to pesticide use and what happens to that pesticide when it enters the environment. Such patterns include where pollinators collect food, where they nest, when they are active, and whether they work alone or together. For example, when pesticides are applied while apple trees are flowering, the likelihood of pollinator exposure increases.

A combination of pesticide exposure and toxicity determines pesticide effects on pollinators—including the impairment of pollinator functions (such as reproduction) or pollinator death. Pesticides may also compound the effects of other pollinator stressors, such as poor nutrition, pests, and pathogens.

When each of these domains and the linkages between them are well understood, integrated pest and pollinator management solutions can emerge. For example, when the rosy apple aphid became resistant to organophosphates, carbamates, and pyrethroids, the only viable alternative was a new class of insecticides—called neonicotinoids—that had the potential to harm pollinators. Researchers developed an integrated approach in which the pest was treated early in the spring, with the least bee-toxic neonicotinoid, before the apple tree flowered, thus reducing pollinator exposure while also protecting the crop. Several States have also implemented systems that alert beekeepers to pesticide applications in the area so beekeepers can restrict bee foraging flights while pesticides are applied.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kaylee and Jason Moody are beekeepers and owners of Moody Bees Honey in Madelia, Minnesota. These first-generation farmers have been in business for five years.

Starting the Business:

Kaylee and Jason got started in the beekeeping business when they moved onto an old farm site near Madelia. The couple grows a lot of their own food and switched to a permaculture system, focusing on the whole system rather than one species, by planting perennial food crops, building swales for water catchment, deep mulching for nutrients, and feeding soil microbes.

Moody Bees Honey began selling their products in 2014. Their current products include table honey, raw honey, and honey infused with garlic, lavender, or hot peppers. The peppers and herbs used for infusion come from other local producers including Alternative Roots Farm and Under the Sun Herbs.

“I’m a local business, so it’s important to me that we keep money in the community,” said Kaylee. “We keep each other and our families in business.”

According to Kaylee, hot pepper- and garlic-infused honey can be used for cooking. Other products include candles, lip balm, salves, and lotion bars.

“Every part of the bee’s work gets used. Nothing goes to waste,” Jason said.

Growing the Operation:

In 2015, they applied for and received their first microloan through USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA), which helped them expand their operation from four hives to 30 and to purchase honey processing equipment.

They slowly grew their operation between 2015 and 2018, receiving a second microloan to increase their total number of hives to approximately 300.

Kaylee was also enrolled in the Farm Business Management Program, a program offered through a community college that partners with FSA. Through the program, the farm business manager assigned to Kaylee helped her keep accurate financial records, as well as financial reporting requirements for her loans.

“It was difficult at first, coming from a small non-conventional type of farm and trying to navigate the waters, but it has really turned around and its awesome to have that resource available,” said Kaylee. “I think more small farmers should consider FSA programs as an option and a resource.”

Keeping the Bees:

The last five years have been difficult on their bees because of the winter weather. FSA’s Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees and Farm-Raised Fish Program helped them recover from the losses it caused.

“In the fall we were having 60 to 75 percent losses in our colonies,” said Kaylee. “It was very devastating. We were very thankful for the success we had with the program through FSA.”

To avoid further losses, Jason and Kaylee decided to move their bees to east Texas during the winter months.

“I always joke that I am now a snow bird at the age of 27, and I’m pretty stoked about it,” she said.

Community of Comradery:

Kaylee is president of the South-Central Minnesota Beekeeper’s Association that meets to talk about issues facing beekeepers.

“It wasn’t just us seeing those losses, it was all across southern Minnesota,” explained Kaylee. “We helped encourage those folks into going to FSA for their losses, too.”

Jason also enjoys the comradery of the beekeeping community.

“Being part of the local bee keeping community is like being part of a big family,” Jason said. “Everyone is always willing to help each other out.”

More Information:

USDA offers a variety of risk management, disaster assistance, loan, and conservation programs to help agricultural producers in the United States weather ups and downs in the market and recover from natural disasters as well as invest in improvements to their operations. Learn about additional programs.

For more information about USDA programs and services, contact your local USDA service center.