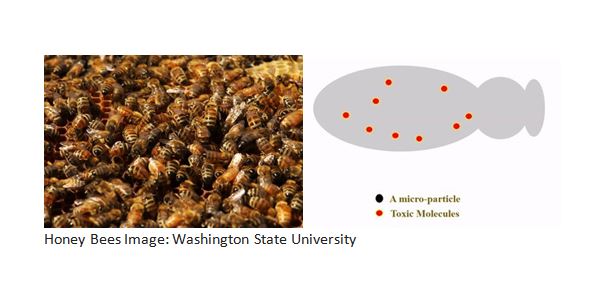

Scientists at Washington State University have created a microscopic particle that could save honey bee colonies from collapse. It attracts pesticide residue in bees. Over time, pollen tinged with itsy bitsy amounts of pesticides accumulates in a bee’s body, reducing the lifespan of each bee in a colony.

Originally, the material is a powder that acts as a magnetic microsponge that absorbs ingested toxic residues. It can be incorporated into a sugar solution that’s fed to bee colonies. Each microparticle is the size and shape of a grain of pollen, making them easily digestible for bees.

Scientists created the powder in such way that beekeeper can easily handle it.

When consumed by the bees, the particles attract and absorb pesticide toxins. Then, they pass through the bees like any other food. Each particle only spends a few hours in their digestive system, which is enough to significantly reduce pesticide residues.

In fact, each particle of Suliman’s technology can remove about 300 nanograms of pesticide residue — much more than bees can survive.

Last summer, to test this new product, Suliman and assistant professor of entomology and manager of the WSU bee program Brandon Hopkins fed around 6,000 bees the microparticles in a sugar solution. Then they tested feces from those bees and found it contained the microparticles. In addition, the bees colonies remained healthy, showing that the microparticles don’t harm bees.

Nanoparticles

This summer, they will test just how well the particles attract toxins in the bees’ bodies by collecting the microparticles after they’ve been through the bees and measuring them.

Recently, a group named BeeToxx — comprised of undergraduate students mentored by Suliman, WSU’s Derick Jiwan, and others — won second place in the Alaska Airlines Environmental Innovation Challenge, taking home a $10,000 prize and beating out 22 other teams. The students had the opportunity to work on a real-world problem that goes beyond what they learn in classes, Suliman said.

This winter, the team involved was one of four to win the Honey Bee Health Coalition’s Bee Nutrition Challenge and also received a $10,000 prize. Their proposal was chosen from among 20 submitted, with only four prize-winners.

“We’re really proud to get noticed for the work we’ve done so far,” Suliman said. “And this will help us keep testing and refining the product.”

We’re really lucky that bees have fairly simple digestive systems,” Suliman said. “Our material is specifically designed to work only on pesticide residues and only at a certain pH level and temperature. So the micro-particles won’t absorb amino acids or anything else a honey bee eats.”

Since they’re still collecting data, the material isn’t yet available to beekeepers. But Suliman is hoping to have the product on the market in the next two years.

“We have proof of concept,” he said. “Ultimately, our goal is to lessen the economic impact of bee decline not only for beekeepers but also for farmers and food prices.”