I recently had a chance to visit the National Bee Diagnostic Centre (NBDC) in the small town of Beaverlodge, Alberta, which is basically an NCIS crime lab for bees. I was greeted by three scientists huddled around a computer screen speckled with green and red dots. They “hmm”ed and “ahhh”ed and occasionally tapped the screen with a finger or a pen. The red dots represented dead “swimmers” and the green were live ones: sperm samples from a queen bee. (The queen stores sperm from multiple worker drones.)

Facing pressures like climate change and pesticide use, bees are in trouble in North America. The health of these pollinators is of upmost importance, so the NBDC is collecting health data on bees across Canada to help this country create a national bee health database. The project, called the National Honey Bee Health Survey, is funded in part by the Canadian government and researchers have been collecting samples for the last three years. The first phase is finishing this year, with the results coming out sometime next summer.

In late June, they released their findings from 2016. Among other findings, the survey showed that bees in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island are suffering from a very high incidence of Chalkbrood—a fungal disease that infects the gut of the larvae. These three provinces have incidences above 31 per cent, while the national average is just below eight per cent. The other provinces all score below six per cent.

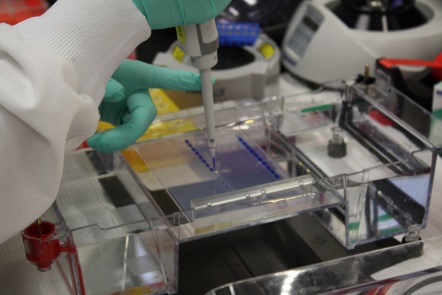

For the survey, honeybees are collected and analyzed for viruses, mite infestation, and hive infections, including Chalkbrood. (The report doesn’t explain provincial discrepancies around the fungus.) Samples are shipped live to the NBDC, which began collecting bee samples in 2013, was the first facility in Canada solely dedicated to figuring out what’s impacting bee health.

So far, said Christy Curran, the NBDC research project coordinator, only Canada Post has been willing to ship live bees. (This despite the fact that FedEx has shipped entire live whales before.) Last year, samples from 314 different apiaries across Canada were collected.

The centre itself was created as a response to beekeepers wanting to know more about what’s hurting their bees, so they also offer fee-for-service testing on honey bees to identify the bacteria, fungi, mites and viruses that might be afflicting them. For this, dead (and sometimes live) bees are sent in by everyone from hobbyists to professional beekeepers, across Canada and around the world.

Honey bees are important for Canadian agriculture. Pollination services provided by beekeepers add an estimated $3 to 5 billion in additional crop value. The NBDC is the result of a partnership between Grande Prairie Regional College and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, a federal agency.

I sat down with Curran and asked her what it’s like to receive dead bees in the mail.

“Sometimes they smell,” she laughed. (This can be attributed to the ethanol used to preserve them.) “Sometimes they’re pretty gross,” she continued, “but it’s really neat and exciting the geography that we’re covering, because Canada is quite big.” The lab has received bees shipped all the way from the Yukon.

The recently released report includes findings based on samples collected from most Canadian provinces and territories, with the exception of Saskatchewan, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Previous years’ surveys only included samples collected in two to four provinces, so it is getting more comprehensive.

“The beekeeping industry has been suffering a large amount of losses during the winter months,” said manager Carlos Castillo, a scientist. “Probably starting somewhere around 2006 or 2007, many beekeepers wanted a diagnostic centre to understand what’s going on.”

Pesticide use is a growing worry, he said. “In general, [beekeepers] are concerned about pesticide use, because beekeeping is very closely related to agriculture.” According to him, farmers are supposed to contact beekeepers when they’re going to use pesticides, so that the beekeeper can contain the colonies and keep them out of those areas for a few days.

“Unfortunately, sometimes there is a miscommunication and hives die,” he said.

Canadians are taking notice of the health of their bees: Health Canada has proposed a broad-sweeping ban on uses of a neonicotinoid pesticide called imidacloprid after it was found that it is seeping into the waterways and harming bees. And this country has six designated “bee cities,” including Toronto. The NBDC is putting in the work to ensure that beekeepers know exactly what they’re up against when their hives take a turn, but it’s up to the beekeepers to use their findings and protect the hives.