A variety of neonicotinoids—harmful to aquatic organisms—are reported in major Great Lakes streams.

The study (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749117344962) is the first to examine the insecticides—gaining notoriety in recent years as a prime suspect in bee die-offs— in the world’s largest freshwater system and suggests Great Lakes’ fish, birds and entire ecosystems might be at risk.

“This study is one of many that shows we know very little about the repercussive effects of pesticides once released into the environment,” said Ruth Kerzee, executive director of the Midwest Pesticide Action Center, who was not involved in the study. “We are told these compounds break down rapidly when exposed to sunlight and, yet, this study shows persistence in the environment long after applications.”

The study comes as draft legislation is circulating in Congress that would remove requirements that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Department and the National Marine Service over pesticides’ impact on threatened and endangered species.

Neonicotinoids are the most heavily used insecticides on the planet—designed to attack the nervous systems of insects and protect crops from damage. Once thought to be relatively innocuous to wildlife higher up the food chain, scientists are increasingly reporting toxic effects.

The chemicals are linked to bee die-offs. Last summer a major study in Science (http://science.sciencemag.org/content/356/6345/1395) reported bees near cornfields exposed to neonicotinoids for a few months via pollen suffered from decreased survival and poor immune systems. In birds, (https://www.nature.com/articles/nature13531) exposure to the chemicals has been linked to population declines.

There’s also nascent evidence the chemicals may directly hurt aquatic wildlife—from tiny organisms to fish—with potential to disrupt entire ecosystems.

“The decline of many populations of invertebrates, due mostly to the widespread presence of waterborne residues and the extreme chronic toxicity of neonicotinoids, is affecting the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems,” researchers wrote in a 2016 review of the chemicals. (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2016.00071/full)

Michelle Hladik, lead author of the new study and a research chemist at the U.S. Geological Survey, said the major risk of these chemicals is to aquatic insects—an effect that could ripple up the food chain.

“If these pesticides are affecting aquatic insects, causing lower populations, it could affect the food chain by removing a food source” for fish, she said.

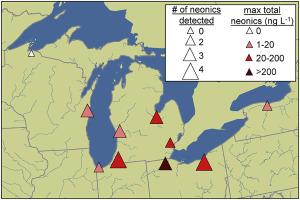

Prior to the study little was known about the chemicals’ presence in the Great Lakes region. From October 2015 to September 2016, Hladik and colleagues took monthly samples from the following rivers that all drain into the Great Lakes:

- Manitowoc River (WI)

- Grand River (MI)

- Joseph River (MI)

- Indiana Harbor Canal (IN)

- Saginaw River (MI)

- River Rouge (MI)

- Maumee River (OH)

- Cuyahoga River (OH)

- Genesee River (NY)

- Bad River (WI)

They found at least one neonicotinoid insecticide in 74 percent of the samples and found three neonicotinoids in 10 percent of the samples. The concentrations increased in spring and summer months—suggesting planting of insecticide-treated seeds is behind the spike. They’re also used by non-farmers in garden and landscaping sprays and products.

Kerzee pointed out that a large percentage of the chemicals detected came from urban areas. This shows “urban use of pesticides has a substantial impact on the health of our waterways,” she said.

Not surprisingly, there was a strong correlation between presence of the chemicals and nearby land cover — for instance, no neonicotinoids were found at the Bad River, which is the only tributary that’s surrounded by forest. Meanwhile, Ohio’s Maumee River, which is surrounded by corn and soybean crops, had some of the highest levels of the chemicals.

Hladik said the levels found in the rivers were similar to levels tested at other sites throughout the Midwest.

She said, though the levels were relatively low, the EPA recently lowered the toxic threshold for certain neonicotinoids and “some of these tributaries are now above that (threshold) for part of the year.”