Alan Harman

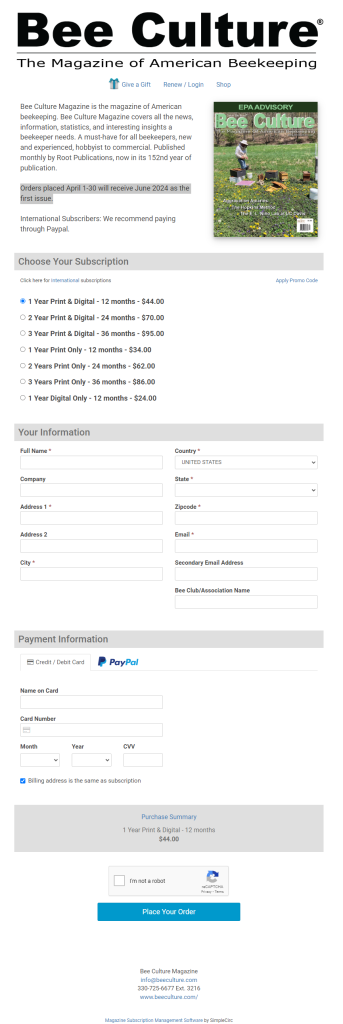

Photo UMF Honey

About a third of honey marketed in the United Kingdom as manuka product from New Zealand does not meet the label specifications.

The figure is contained the annual strategic assessment carried out by the National Food Crime Unit for the Food Standards Authourity and Food Standards Scotland of the food crime threat to the UK’s £200-billion (US4282.3-billion) food and drink industry.

“UK testing has identified non-compliances in around a third of tested samples of products labeled as Manuka, in terms of quality, declared activity or botanical origin compared to the declarations on the label,” the report says.

Manuka honey attracts a premium price based on its perceived positive health benefits.

“As with similar premium products of this nature, this presents opportunities for offenders to pass off inferior honey products as Manuka in pursuit of fraudulent profits,” the report says.

“Such fraud may already be apparent. Some media reporting has suggested large disparities between the quantity of Manuka produced and that sold,” it says. “This has not, however, been confirmed by any official figures from the New Zealand government.”

The report says the authenticity of Manuka honey can be challenging to establish.

“Analysing pollen within the honey can be helpful, but Manuka pollen can be hard to distinguish from Kanuka pollen,” it says.

Kanuka is a plant that grows in similar geographical areas, but it tends to have lower levels of methylglyoxal, the chemical purported to give Manuka health benefits. There is research underway to enhance differentiation techniques, the report says.

“In order to protect consumers and their own export market, New Zealand government bodies have worked to standardize and clarify what can be used on Manuka labeling,” the crime unit says.

“A robust definition is expected by end of 2016 which will provide clarity for consumers around both the content and the benefits of these products.”

The unit says there is no intelligence at this stage to suggest organized criminal exploitation of the lack of clarity around Manuka authenticity or unlawful labeling that suggests health claims or makes therapeutic claims.

“The likely appeal to the criminal of capitalizing on price differentials between standard and Manuka honey, however, remains substantial, as does the potential to exploit the lack of guidance regarding labeling standards,” it says.

The unit says there is widespread fraud with regular honey in the European Union.

“In 2015, an EU-wide exercise sampling and testing honey identified levels of non- compliance (principally around sugar content and botanical origin), although not all such non-compliances will have originated in fraudulent activity,” the unit says.

“This work continues and there should be additional clarity on the outcome of this exercise later in 2016. This will enable a deeper understanding of the role of dishonest conduct within these non-compliances.”

Meantime, the crime unit report says the Internet continues to transform the shape of the marketplace for all types of products, including foodstuffs, while also introducing new opportunities for fraud.

The UK’s online grocery market now is valued at £9.57 billion (US$13.5 billion) a year and this is expected to grow to £17.2 billion (US$24.3 billion) by 2020. Three out of ten UK consumers bought their groceries online in June 2015, with one in nine buying most of their groceries on the web.

And where there’s the Internet, there’s crime.

The online sale of meat by small-scale or unregistered providers is repeatedly observed in available intelligence. This effectively removes traders from the scrutiny which comes with registering as a food business operator or having a physical business premises.

An increase has also been noted in online wet fish auctions by small-scale operators, a further opportunity for dishonest fish species substitution.

“Further work will be required to substantiate and quantify the criminal threat posed by internet sales,” the report says.

The international nature of domain registrars and web-hosting presents challenges to the effective investigation and enforcement of criminal law online,” the unit says.

The report says European distribution fraud (EDF) is growing.

EDF involves a manufacturer or supplier of a commodity (often based elsewhere in Europe) being contacted by a prospective client claiming to be from any one of a number of major and well-known UK businesses, predominantly food businesses.

“The individual places an order which is then dispatched to an address in the UK but never paid for. Consignments are delivered to UK locations that are neither used by nor known to the genuine UK retailer who receives the invoice from the European supplier but has no knowledge of the order. The supplier ultimately suffers the financial loss.

“This method of offending can carry food safety implications, particularly if the commodity in question is perishable and not handled in accordance with food hygiene regulations,” the crime unit says.

Offenders are known to use email addresses with domain names similar to the genuine businesses they are seeking to impersonate. Company logos, websites and contact details may all be cloned to provide a further illusion of authenticity

Sometimes the delivery driver is asked to change the destination mid-transit.

“On occasion, offenders have been known to collect goods directly from the supplier,” the unit says.

Industry losses as a result total in excess of £7.5 million (US$10.6 million) since 2009.

Recorded instances of EDF span the UK, but with a particular focus on the Greater London area. Suppliers from 28 countries have been affected, the top five being in Western Europe, with the UK second on this list in terms of businesses affected.

In terms of food, the five main commodities involved have been olive oil, wine, fruit, coffee and fish.

“There is no intelligence to indicate why these specific food stuffs have been targeted although olive oil and wine may be attractive because of their popularity, shelf life and intrinsic value,” the unit says. “It may also be because the offenders have a market in mind to which they can sell the goods.”