The Business of Bees: Part I of III

North Carolina has a lot of beekeepers. We’re ranked in the top ten states for most hives, and we have the most beekeepers of any state in the U.S. I daresay that large number of beekeepers may be partially due to the combined efforts of the NCSU Apiculture program, the fantastic group of NC Apiary Inspectors, and the NCSBA’s positive marketing with the public. That being said, we are a state of primarily hobby beekeepers with less than 10 hives per person. We are not a commercial beekeeper powerhouse like Texas or Florida (which should perhaps be looking into subaquatic bees after the 2017 hurricane season), but there is still a lot of room for beekeeping profitability.

As a hobbyist beekeeper, where do you start if you have decided you want to move to the next level? First, you should make an assessment of your current standing. Here are some things to consider:

- Do you have enough time to dedicate to the maintenance of enough hives to make a profit?

- Do you know how many hives it would take to make a profit?

- Is making a profit your goal (as opposed to things like personal interest, tax write-off, pollinating your own farm, having the heaviest hive in Annie Krueger’s hive scale project, etc.)?

- What have been your biggest issues as a hobbyist beekeeper and how can you address those on a larger scale?

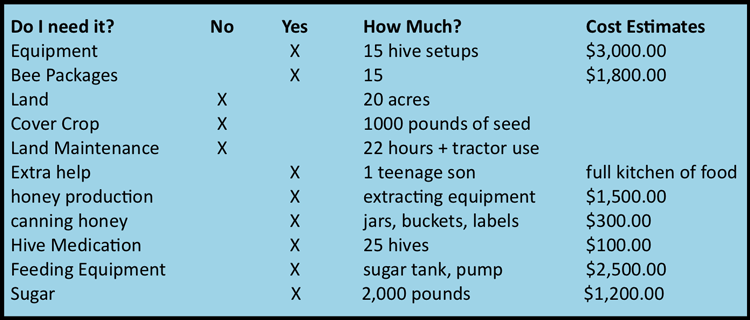

After you’ve made an honest assessment that no, you don’t have time to do it but you’re going to anyway, then you need to figure out a few things, like what equipment do you currently have and what equipment would you need in order to expand. As an example of some things to think about, here’s a quick excel sheet with one type of planning strategy:

This might not cover everything you would need, but in this example, it assumes that you are some level of farmer with access to land and a tractor and can harvest your own cover crops, and also have a teenage son who will work for food. This hypothetical hobbyist does need a decent amount of new bee equipment and extraction equipment.

Based on this situation, you’re looking at around $10,400 on the high end of expenses. If you sell honey for $10 a jar (easy for a math example) then you’re looking to sell 1,040 jars of honey to break even in the first year. However, if you can use your expenses to create a tax basis, you’ll at least be able to depreciate the larger purchases or count them as a business expense. In real life, I’m sure your situation is totally different than my fake one here, but the point is to be able to organize your thoughts on paper in a way to make sure that you have financial goals and you can realistically achieve them. You don’t want to buy a commercial honey extractor when you have 40 hives (I mean, you might want to but it’s not a good idea) but you do want to make yourself a budget for how much you can realistically afford, what you can come up with on your own, and how do you plan to make money to pay for the things you buy?

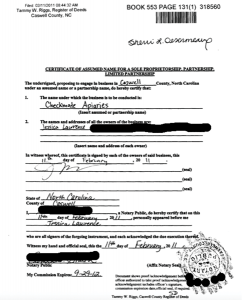

When you start small, I’d go with a Sole Proprietorship in the beginning. When I started Checkmate Apiaries, I filled out a form through the county Register of Deeds and had it notarized. I’ve since been able to count all of my beekeeping expenses as a business expense and kept up with my profits for tax purposes. If you happen to buy a larger piece of equipment, such as a trailer for hauling bees, you can depreciate that for ficw years. Some things, like a building (honey house or storage), may be depreciated for 15 years. You can also count mileage between sites, or for pollination contracts.

When you start small, I’d go with a Sole Proprietorship in the beginning. When I started Checkmate Apiaries, I filled out a form through the county Register of Deeds and had it notarized. I’ve since been able to count all of my beekeeping expenses as a business expense and kept up with my profits for tax purposes. If you happen to buy a larger piece of equipment, such as a trailer for hauling bees, you can depreciate that for ficw years. Some things, like a building (honey house or storage), may be depreciated for 15 years. You can also count mileage between sites, or for pollination contracts.

If you decide to go bigger, what are you options? Well, you could start with honey production, and sell packages of bees for any colonies above what you can handle. You could try to intensively manage your bees and grow quickly with little profit for a few years, then only sell bees. Packages are most likely your biggest bang for the buck, but only if you have the ability to manage your bees year to year in a way that yields high volumes of healthy bees. You could also collect pollen baskets for sale to either farmers’ markets or places that rear non-Apis bees. If you have enough colonies, you can also start looking at pollination services. There’s always the possibility of doing multiple options simultaneously, but as with everything, it takes a lot of time and effort. Colonies for the purpose of producing packages are not managed in the same way as a colony to be used for honey production. Colonies for pollination aren’t managed like either of those options.

You may also be the home master chef vs. high volume restaurant cook. Maybe you have the most amazing beekeeping skills ever on a hobby level, but when you bump it up to 25 hives, everything falls apart because you weren’t ready for the scale. Alternatively, you may find your niche in managing hives for something that you hadn’t really tried before. If grafting queens is your thing, you may find that setting up a high capacity area with nucs and colonies to support that may be your new biggest income.

Another option for your business is swarm removal. Sometimes, swarms are the easiest thing in the world to catch, and you have free bees. Sometimes, they just suck and go somewhere stupid (it’s obviously not stupid to them though). You may even be able to become proficient at swarm removal from houses. If you have carpentry skills, there’s some decent money for removal and repair. I’ve done wall removals before, and depending on the severity, I am not the person to fix that back. There can be some legal trouble here, so make sure you get something in writing beforehand that the owner isn’t going to hold you responsible for damages.

As a Sole Proprietor, there’s really no separation between you and your business, but it is now a separate entity that can have a name and an identity. You can register a name if it is something other than your own name, and make a logo for your products. Your business would also be eligible for SBA loans that you would not be able to personally receive. You are also responsible for all debts incurred, and would be held legally responsible for anything that happens under your business. This isn’t really anything different than your hobby in that it’s basically the same liability you always had, but a bit more public. The United States does have a nice loophole for married couples with a Sole Proprietorship where one person can be the Proprietor while the spouse can work for the company without having to declare the business a partnership for tax purposes.

As a Sole Proprietor, there’s really no separation between you and your business, but it is now a separate entity that can have a name and an identity. You can register a name if it is something other than your own name, and make a logo for your products. Your business would also be eligible for SBA loans that you would not be able to personally receive. You are also responsible for all debts incurred, and would be held legally responsible for anything that happens under your business. This isn’t really anything different than your hobby in that it’s basically the same liability you always had, but a bit more public. The United States does have a nice loophole for married couples with a Sole Proprietorship where one person can be the Proprietor while the spouse can work for the company without having to declare the business a partnership for tax purposes.

If you take your bees to the next level and find that you have a pretty good shot at the route you choose to take, be it pollination services, queens, honey, hive products, or some combination thereof, it might be time to start thinking about leveling up. I would suggest having a few years of solid profit margins though, just to make sure you are in a safe place. Maybe you also have someone who can help you expand your business where you can produce packages and they are the most amazing queen grafter to ever walk the face of the earth. In this case, it might be time to move up to an LLC. It’s a whole different ballgame legally, but it’s definitely the way to go. Stay tuned for Part II to learn from my mistakes when changing from a Sole Proprietorship into a Limited Liability Company. Hopefully, you can do it better than I did – that’s a pretty low bar to hurdle.

Jessica Louque and her family are living the dream in North Carolina.