Beekeeping in the Gap.

New and recycled containers – when are they clean enough.

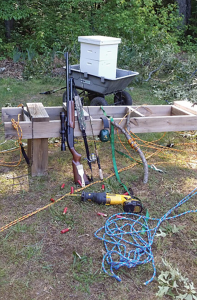

Odds and Ends – Shooting down a swarm.

A personal note.

Keeping bees in the “gap”

An interstitial space or interstice is an empty space or gap between spaces full of structure – a gap. For the past 30 or so, we have been keeping our bees in the interstice formed between mites not being in our bees and mites being in our bees. Presently, we know mites are in our colonies, but we do not yet have conclusive control procedures to rid our bees of them. We know the question – “How do we effectively control mites?” – but we don’t yet have the final answer.

In the past three decades, we have tried a plethora of remedies. None have positively risen to the top of the “control procedures” pile. Though it has been the goal of scientists worldwide, nothing has been found that will let us routinely keep bees as we did in the 70s. Frequently, today’s bees seem lethargic and weak. Replacement queens don’t always seem great. Why? I don’t know.

Welcome to bee life in the gap. It’s the life beekeepers challenge until comprehensive answers are developed.

A resolute beekeeper – me

Last year, during the second week in December, snow had fallen and was crunching beneath my feet as I returned from my storage barn. It was bright day so it was easy to see the little black spot on the brilliantly white snow. It was a dead bee that I duly noted. “Humph, odd” I thought. A few more crunching steps and yet another black spot appeared. “Whoa!” In fact, there were dead and dying bees everywhere. Many were dead but just had not finished dying. What in the world is going on? The three beehives in question were near the storage barn. They were from established colonies that had built up nicely last Spring. I had given them full frames of capped honey, provided protein patties, and added plenty of extra supers. They exhibited good flight all Spring and Summer. Now, this? Where were all these dead bees coming from?

In fact, they were coming from the middle hive of my three hives. It was 28°F outside on a bright, still day. Yet the hive was alive with frantic bees at all entrances and a small pile of dead bees accumulating on the ground. They appeared agitated – as though they were all trying to leave at once. They seemed absolutely eager to die. As I stood there, watching in confused amazement, a few bees departed on suicide flights. What was going on? Old combs? Stores from toxic sources? I don’t know. This mystery colony survived the Winter; though it must have been set back some. Later in this past season, I could not tell the difference between it and my other colonies. For a while this colony was in the “gap” of my bee knowledge. I don’t know what happened, so I am not sure what to do for the upcoming season. When it happens, I will deal with it.

This is a single example of beekeeping in the gap, but the same could be said of oh, so many other beekeeping issues. These unknown areas like: poor queens, lethargic colonies, late season swarms, and on and on are examples of beekeepers striving to get through issues that have no defined answers. In a way, this informational void keeps beekeeping interesting and challenging. Such everyday beekeeping unknowns make up the core of beekeeping meetings. I offer some current topics below.

Some thoughts on unexplained die-offs

– both yours and mine

Reusing old combs

Most beekeepers recycle old combs as they manipulate their colonies. The potential problem with this procedure is a low-key subject that is periodically brought up by various scientists and beekeepers. Beeswax is a chemical blotter – essentially a liver. It seems that any chemical that comes near it is partially absorbed by beeswax. It has been postulated that, at some levels, harmful intensities of residues are reached that negatively affect developing brood. Testing combs is impractical for nearly all of us. How long to use combs, when to replace, and how to replace are some of the common unanswered questions in this area. This is one of those partially answered questions in beekeeping. We know that chemicals accumulate, but when is too much too much?

Right now – best guess recommendation – change every three to five years. (I will do my best, but I will also expect to fall short.)

Too many colonies die during Winter months

Winter colony deaths are like New Year’s Resolutions. Each Winter/early Spring, I make a list of things I will do differently this upcoming season. I am now leaving plenty of honey – plenty. That is a change from seasons past. In fact, I commonly have honey left on the colony for the splits/packages that I will be installing next Spring. But for six years or so, some of the most unexpected colonies have died; and on occasion, some of the weakest colonies survive. Go figure. Am I just mis-remembering? Decades ago, did populous colonies sometimes die and I have just forgotten? Even so, I want to address this abnormal Winter flight that some of my colonies have exhibited for several (even many) years now.

Cleaning both new and old honey jars

Beekeepers quickly begin to accumulate “pre-owned” honey jars. Their future use is generally uncertain.

I got this question from a county extension educator. Honestly, I had never truly thought about discussing the answer, so I had little published information to provide. After some consideration, I composed the following comments. Tell me if you do not like something I have said here (or anywhere else).

There has been some discussion at our monthly meeting that new bottles come from the manufacturer ready to be filled and do not need to be sanitized. Others say they need to at least be washed and well dried but not sanitized.

1. New, undamaged and unopened cases of inverted glass containers are suitable for filling with honey without pre-cleaning. Check them anyway.

If the honey bottler wants to wash or otherwise clean jars, absolutely no harm is done. (See section 7 below)

After bottle filling, fingerprints and residual honey should be wiped away with warm water and a clean cloth.

Cases containing broken jars with glass shards would cause remaining unbroken jars to be scrupulously inspected for chips or cracks. Usable jars from damaged cases should be rinsed with water. After drying, such jars should be wiped to removed water stains.

2. The lids for glass bottles should be new, with properly fitting seal inserts. Ideally, they should not be scratched or dented and should fit tightly.

3. Plastic bottles that are shipped loose in large plastic or corrugated boxes or bags should be blown out with compressed air and inspected for plastic pieces or any other contaminants1.

4. There are several variables.

If any glass or plastic containers were purchased secondhand or in open shipping containers or in small lots that are repackaged, such honey containers would benefit from a warm water rinsing.

If the bottling operation is viewable by customers, jars should be rinsed, air dried and wiped before use. The purpose is not to trick the customer, but to reassure the customer that this is a perfectly wholesome product packed in a clean environment.

If the product is bottled in the vicinity of other activities (at farmer’s markets or street markets), the honey bottler should be vigilant for insect or environmental contaminants (dust, leaf parts).

5. Reuse of honey containers.

Customers logically want to reuse any container that can be reused. It is common to have containers returned to the honey bottler.

- Accept such containers, but seriously consider not reusing them.

-The total use history of the container is unknown.

-Plastic containers are more difficult to reuse and have a much shorter use life. In most cases, plastic containers should be recycled.

- Lids can rarely be reused.

- If containers are reused, obviously, they should be washed with soapy water, dried and then inspected.

Specialty reuses of honey containers

- Personal use by the bottler, or family members, etc.

- Items other than honey – including non-food uses.

Using recycled honey jars for toxic materials happens. If seriously toxic, consider attaching a content label.

6. Honey is a remarkably stable and naturally wholesome product. In the natural world, honey is produced by bees, stored in combs, and stocked in trees or other natural cavities. Consequently, honey, as a food, is stable and storable. Naturally occurring hydrogen peroxide and very low moisture content desiccate most (all?) microbial growth known to science at this time. Even so, all honey bottlers must respect the purity of honey and the favorable opinion of consumers. Cleanliness is always an absolute requirement.

7. Individual State Department of Agriculture regulations and recommendations supersede anything recommended in this listing.

Odds and Ends

This time it worked.

From Mary T. in VA.

We roped and toggled the branch so the swarm wouldn’t just drop to the ground if a clean shot went through it. We got the ropes up there by my adult son casting his fishing line with the ropes attached. We’ve all been on active duty at one point or another, so that’s our excuse for capturing at “almost all means necessary” and NEVER giving up. The oddity of all this, is it’s the only swarm we’ve ever captured that decided it didn’t like the hive we put it in. It flew the coop 24 hours later.

We capture only our swarms from our hives. They seem to crawl over me but I haven’t been stung during a swarm catch. I do plug my ears/nose with cotton and wear eye goggles because it’s unnerving for me to have them crawling in and out of those. When the bees crawl around my eyes, it itches/tickles, so I wear goggles. We’ve gone from three to eight hives and given away seven swarm catches. We hope that’s all we do. It’s hard to let your $$ fly off even though we don’t sell bees/honey.

An apology and an explanation

My Mom passed away in early October 2016. It took her several months to reach the final point. She was 91 years old for four short days. Making the experience more difficult, she and I live 850 miles apart. My wife and I frequently visited and commonly stayed for a week. During this confusing time, I increasingly began to fall behind in responding and communicating with those of you who wrote me, frequently sending photos and suggestions. Though I know I have a good excuse, I am still sorry that I neglected some of my correspondence. As I can find these neglected interactions, I will respond – no mater how late.

To the NJ Beekeepers, whose meeting was seriously disrupted by my personal events, I offer a particular apology. As soon as I can, I will make it up to the group.

Thank you, Jim.

Taking a risk…

Thanks to the Iowa Honey Producers Association and to the California State Beekeepers Association for hosting me at their November 2016 meetings. I had a great experience at both events and, as usual, I learned much more than I could give. Both groups were in good beekeeping spirits. It felt good to feel good about beekeeping.

Dr. James E. Tew, State Specialist, Beekeeping, The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Auburn University; Emeritus Faculty, The Ohio State University. Tewbee2@gmail.com; http://www.onetew.com; One Tew Bee RSS Feed (www.onetew.com/feed/); http://www.facebook.com/tewbee2; @onetewbee Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/onetewbee/videos

Dr. James E. Tew, State Specialist, Beekeeping, The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Auburn University; Emeritus Faculty, The Ohio State University. Tewbee2@gmail.com; http://www.onetew.com; One Tew Bee RSS Feed (www.onetew.com/feed/); http://www.facebook.com/tewbee2; @onetewbee Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/onetewbee/videos