James E. Tew

Stay Connected

http://onetew.com

By: James Tew

Frozen honey and how bees eat it – possibly.

Winter stores for the wintering colony.

Consuming frozen honey

Honey bee colonies – anywhere in the world – require some way to store food products for lean times. Such foodless periods occur in all climates. While stores are required anytime there is a dearth, the Queen Mother of all dearths is a long, hard cold Winter.

After reading the simplest of bee books, beekeepers, new and old, know that bees require honey as a Winter food source. No doubt, pollen is just as important, but my discussion here pertains to eating frozen honey during Winter months. To my knowledge, pollen plays no integral part in bees’ consumption of Winter honey. Bees require winter stores. We all repeat it. We all know it, but what I personally don’t fully understand is exactly how bees eat frozen honey food stores.

Honey on left is at 10°F while honey on the right is at 70°F. For this photo, I laid the left jar on its side to show the honey thickness. Even the honey on the right could not be consumed by bees without dilution.

Much of this country just experienced a very cold Winter. In northeast Ohio, where I and my bees reside, it was very cold only a few weeks ago. I know, I know that U.S. states father north and all of Canada chuckle at Ohio’s opinion of cold, but -10°F is cold anywhere that temperature occurs. (At this point, I begin to wander away from apicultural science and amble more toward conjecture. Be warned.)

Right now, it is about 8°F outside. The wind is still, so the wind chill temperature is also about the same. In my hives that I can see in my backyard apiary, honey stores would be about that same temperature. That’s cold honey.

Yes, I know – the healthy wintering colony gives off a bit of heat – about the amount of heat from a 60W incandescent lightbulb. Would that byproduct heat not warm the honey (some)? I’m sure it would, but would that bit of heat be enough to liquefy a significant part of colony’s honey stores to the point that it could be drunk using bees’ lapping-sucking mouthparts. I don’t think so. That frigid honey is going to be very, very thick. Sticking the (very) rough equivalent of a plastic soda straw in that thick honey would not be a practical way to eat cold honey. You try giving a pull on that straw stuck in that frigid honey.

Having no teeth or chewing structures, honey bees do seemingly have a way of returning the honey, in small amounts, into a liquid form at those low temperatures; indeed, at any temperature.1 I think bees’ cold honey consumption procedure must be like my grandkids licking a lollypop. Water (saliva?) is used to liquefy small amounts of frozen honey. Now liquid water in a wintering colony, at such low temperatures, is a hypothetical can-of-worms. Where do bees get a store of liquid water when the temperature is so low?

Do wintering bees lick ice to generate liquid water? I don’t know, but if I’m allowed a guess, I would suspect they do not routinely do this.

My reasoning for this answer is that an individual bee would need to be very near the ice source that is to be licked. I suppose that could happen, but for a bee searching for ice or frost (which has little odor in the dark hive) in a frigid hive, the wandered distance would have to be very nearby or the bee will quickly chill, sit immobile for a while, and then die from cell lysis that causes compromised cellular membranes. If bees were holding any thin liquid in their crops, I suggest that it also would freeze. That’s not good (if my guess is correct). An individual bee within a wintering hive getting only a short distance from the warmth of the cluster is quickly in serious trouble.

Though I have personally said many times that internal frost and ice can be sources of Winter water for a colony, I now second-guess that comment. Gathering water from internal hive sources when the temperature is below freezing does not seem to be practical.

Wintering colony water use

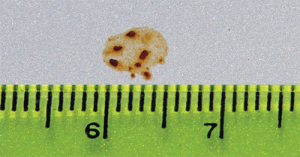

To the best of my ability, the pictured bee is 9/16” (0.563 in). I mean seriously – considering everything else that is within that little bee, how much water can she physiologically hold – a full drop? I don’t know, but it simply can’t be much. Humans are accustomed to full glasses of water, but I don’t think that individual bees consume huge amounts of water per bee.

To the best of my ability, the pictured bee is 9/16” (0.563 in). I mean seriously – considering everything else that is within that little bee, how much water can she physiologically hold – a full drop? I don’t know, but it simply can’t be much. Humans are accustomed to full glasses of water, but I don’t think that individual bees consume huge amounts of water per bee.

Like water on Mars

Apparently, there is abundant water on Mars. Whether or not ice or liquid water is readily available on that planet is still being reviewed. As on Mars, in the wintering colony with ample honey stores, there is an abundant water source in the honey reserves. The frozen honey is probably about 16.5 – 18.6 percent water.

If any of my guessing is in any ball park, that little bee pictured above has access to abundant water that is a component of honey – if it can be thawed or at least warmed. Using her own miniscule amount of internal liquid water, I think she can consume cold honey. To do this, (1) she must be warm at the outset; (2) she has to lick/dilute the thick, cold honey, and (3) she must acquire a saliva/honey mix held in her crop that subsequently passes to her true stomach (ventriculus) where digestion occurs. Digestion processes provide energy to power her flight muscles which are used to generate heat within the wintering colony – ergo – colony warmth during cold periods.

But now I’m stuck

To put some general estimations on this frozen honey water reserve, see if this works. In Ohio, it is commonly recommended that a wintering two-story colony have about 68 pounds of honey reserves going into Winter. If the honey is 18.6% water, that will result in the production of about 1½ gallon of water over the Winter months.

Now I’m stuck. I have gone from, “Where do bees get liquid water within the wintering colony to how – over the course of the winter – do bees get rid of 1½ gallons of by-product winter water?” Do wintering bees in the center of the cluster need the same water quantities that bees at cluster edges need? I don’t know. Do all bees within the wintering cluster, if possible, eat Winter stores or is it given to them by other bees nearer the food gathering site. Year round, bees routinely transfer food stuffs (Trophalaxis) between themselves. This transfer could happen. In fact, I would guess that it does happen.

Yet another guess…

Surely, any bee, anywhere within the colony, and at any time, would use whatever means necessary to get food when energy was required. Yes, some bees have their food stuffs delivered to them, while other bees are literally foraging within the hive for honey that may be very thick and cold. Such cold honey needs processing before it can be consumed. Ultimately, all bees would appear to eat diluted honey as their primary carbohydrate source. That dilution would seem to be from a saliva/water mix and thick honey that is licked in order to consume it. In this way, all bees within the colony are given both carbohydrates and a drink of water when they get their diluted honey meal.

But then there’s the rectum and other beloved internal organs . . .

I am going to speculate that water can only enter the bee through the bee’s mouth. I have not found any absorption or humidity procedures that allows water to enter a bee in other ways.

The water that the earlier bee got from her diluted honey meal passes through all the digestive system, along with other materials and waste products, until it enters the rectum. Other things happen to other products, but staying with the water theme here, water is reclaimed via rectal pads that are in the rectum. That reclaimed water is released into the hemolymph where it roams around through the bee until the bee becomes “water logged” with byproduct water.

To maintain osmotic and salt balance, the Malpighian tubules begin to reabsorb water from the bee’s hemolymph and dump it (and other products not discussed here) into the rectum again. I am unable to explain how the rectal pads in the rectum and the Malpighian tubules in the hemolymph of the body cavity come to an agreement about water levels. Excess water stays in the rectum (sometimes for months) until cleansing flights can be taken. The amount of excess water in a particular bee determines the “liquid splat” content of bee feces on your car. Watery spots are released by bees that are nearly water logged. Firmer fecal spots are released by bees that had little excess water. There are also possible diarrhea issues that are beyond my scope here.

Not all colonies are the same

But you already knew that. Feral nests are commonly much smaller than intensely managed colonies. Small populations and smaller amounts of honey stores mean that these small colonies can nearly stay in a small, confined area of honey stores throughout the Winter. I speculate that “moving upward” as managed colonies do as the Winter advances does not always occur in small colonies that are essentially always on their honey stores.

But a smaller managed colony in a single deep would have a similar wintering scheme to a larger colony. It seems logical, but I have no data to support this concept of smaller colonies not moving far from their honey stores.

Venting the outer cover during Winter months

As wintering bees flex their flight muscles at a high rpm without moving their wings, they generate heat within the cluster. The outer insulatory layer of older bees try to hold that heat in, but it’s simply not possible to retain all of it. Heat rises and water condenses on the inner surface of the hive top. (Is this a bit like water accumulating on the ceiling caused by an unvented propane heater?) As they burn their honey fuel, they generate water as a byproduct (So you recall the 1.5 gallons from earlier?). Beekeepers need to provide a vent at the top, but then later in the season, the humidity needs to be raised to allow brood production.

Water in and water out…

Frost on the inner surfaces of both lids. I don’t sense that this is a suitable water source for wintering bees.

This entire cold honey thread came to my mind because my wife and I were to present a short wintering discussion to my grandkids elementary school bee class. (Ironically it was so cold and snowy that school was cancelled that day.) As my wife (Grandma) and I (Pop-Pop) were trying to come up with a plan to explain how bees survive a Winter, the wind was howling outside my living room window. It was a good Winter storm.

Part of our plan was to use honey straws to give the kids a sample of the food which that bees consume to survive the Winter. I briefly had the thought, “Wow, we should freeze these honey straws to give them a real understanding of bees’ winter food.” To which I thought, “Well, how do the bees do it?” I realized that I wasn’t sure; hence, your torture here today.

This is my colony winter water story, but I am not necessarily sticking to it. I could be wrong in oh-so-many places. I’m confident someone will point them out – as they should.

As the Winter weather temperature begins to drop and stored honey thickens, internal hive foragers, only require the tiniest amount of water (or saliva) to liquefy the surface of their cold honey stores – thereby collecting a honey/water mix. I suspect all bees can do this, but I also would guess that much of the task falls to bees that are nearest the stored honey. In “eating” this honey, the bee gets both a sugar meal and some water to go with it. Therefore, all wintering bees should have similar food quantities. Yes, there are cluster mechanics failure at times resulting in the colony being damaged or even killed. As bees consume diluted honey, water levels accumulate in the wintering bee. Cleansing flights are required on warm days during the Winter. Bees also lose moisture via respiring and around their cuticular membranes.

It’s complicated . . .

Wintering bees need water, but only just enough. Bee brood requires controlled humidity levels – but not too little and not too much. What’s a beekeeper to do? Only the best they can.

I suspect this discussion could have been painful for some of you. It’s much ado about very little. But when I hear generalized statements given as information for general hive management such as this one, “Provide a dependable water source for your bees.”, there is so much more to that simple recommendation. Here I have offered my guesses with some occasional facts.

At this point, I am reminded of H.L. Mencke’s well known quote:

For every complex problem, there is a solution that is simple, neat, and wrong.

That quote could describe my efforts at understanding bees beyond my ability.

Thank you.

If you made it through this piece, thank you.

I used these sources for some of my information:

http://honeybee.drawwing.org/book/crop

The Hive and the Honey Bee, 2015 edition, Joe Graham, editor

Understanding Honey Bee Anatomy: A full color guide, 2012, Ian Stell, author

1It would seem that honey bees dilute honey – at any temperature – with water before being able to lap-suck it into the crop. A bee’s crop is essentially a cargo bay for product transfer. This structure is also instrumental in absorbing water from the central body cavity. When full, the crop is about 10x the size of the empty crop. The crop generally has a capacity of about 40mg or 3/5s of a single drop.

Dr. James E. Tew, State Specialist, Beekeeping, The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Auburn University; Emeritus Faculty, The Ohio State University. Tewbee2@gmail.com; http://www.onetew.com; One Tew Bee RSS Feed (www.onetew.com/feed/); http://www.facebook.com/tewbee2; @onetewbee Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/onetewbee/videos