What I Learned In Cuba!

By: Malcolm Sanford

Jose Martí airport was more modern than I expected. It differed in two ways from others.

Luggage is checked by x-ray just as carefully coming in as going out. The arrival area features a table where a gaggle of nurses dressed in white collects the health form every arriving passenger is required to fill out. This is the first hint of the socialized structure that awaits anyone entering the country. It makes sense; health care is free in Cuba, so it’s wise to collect data on the health all human arrivals.

Much of Cuba resembles what is seen in other parts of Latin America. At first glance, the place reminded me of a country I had visited several months previously via the Nicaraguan Bee Project Both Nicaragua and Cuba have a somewhat similar checkered relationship with the United States of America, and revolutions have changed all three of these New World countries in countless ways.

Most citizens of the U.S. would be hard pressed to relate much of Nicaraguan-U.S. story. Not so for Cuba, a country sitting 90 miles off the Florida Keys, which continues to be affected in many ways by its northern neighbor. The Spanish American War (“Remember the Maine”, Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuban Missile Crisis, Mariel Boatlift, Wet feet Dry Feet Policy, and Operation Peter Pan all come to mind. In addition to more details on these still controversial situations, there would be much to learn about beekeeping practices from my first trip to the island.

I journeyed to Nicaragua to see how North Americans were teaching beekeeping to the rural population earlier this year. The country continues to slowly recover from its series of revolutions, which, according to a wikipedia post, “brought immense restructuring and reforms to all three sectors of the economy, directing it towards a mixed economy system. The biggest economic impact was on the primary sector, agriculture, in the form of the Agrarian Reform, which was not proposed as something that could be planned in advanced from the beginning of the Revolution, but as a process that would develop pragmatically along with the other changes.”

The beekeeping I saw being taught in Nicaragua was rudimentary, with a minimum of training and equipment being supplied mostly via non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and practically no assistance from the state. There was plenty of optimism in the country, however, mostly fueled by the promise of organic honey, being principally produced and exported by the Danish company, Ingemann, but also by a growing domestic market.

Cuba too is coming out of its own revolution(s). Instead of a “mixed” model, however, Wikipedia reports: “Cuba has a planned economy dominated by state-run enterprises. Most industries are owned and operated by the government and most of the labor force is employed by the state.” However, tourism and other activities appear to be driving some parts of the economy toward a more private enterprise model. Among these shoots of what might be called “emerging capitalism,” one can find the “paladar,” a small-scale private restaurant catering mostly to the tourist trade.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990 inaugurated what is called the Special Period in Cuban history. Abrupt withdrawal of Soviet economic support in place since the 1960s produced conditions that rivaled the effects of the Great Depression of the 1930s in the United States. Again, according to Wikipedia, “The early stages of the Special Period were defined by a general breakdown in transportation and agricultural sectors, fertilizer and pesticide stocks (both of those being manufactured primarily from petroleum derivatives), and widespread food shortages. Australian and other permaculturists arriving in Cuba at the time began to distribute aid and taught their techniques to locals, who soon implemented them in Cuban fields, raised beds, and urban rooftops across the nation. Organic agriculture was soon after mandated by the Cuban government, supplanting the old industrialized form of agriculture Cubans had grown accustomed to.”

The above circumstances, it turns out, are key to understanding the current trajectories of the Cuban economy, including its beekeeping enterprise. The results are still being played out as the country continues to recover from this difficult time.

Instead of teaching apiculture, my experience in Cuba would be one of learning about the activity on a tour organized by Transeair Travel out of Washington, D.C. U.S. citizens must generally be participating in some kind of organized (usually cultural) activity in order to obtain a visa. Some eleven eager beekeepers thus arrived in Cuba to begin an adventure in experiencing the Cuban culture, as well as the beekeeping practices found on the island.

Initially, I expected something akin to my Nicaraguan beekeeping experience, but was surprised at the development and sophistication of the enterprise. Our introduction was a detailed history of Cuban apiculture from a person who is one of the leading experts on the craft, and current head of the Apiculture Research Center in Havana. Trained and licensed in Bucharest Romania in 1976, he received his masters degree at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, with a specialty in animal management and nutrition in 1992, and has since traveled the world bringing the Cuban beekeeping experience to many countries. He was instrumental in developing and coordinating the 12th Latin American and 6th Cuban Apicultural Congress in Havana in 2016.

According to Lic. Pérez Piñeiro, honey bees were first introduced in some scale via the Spanish from Florida in 1764. By 1770, the island was a major producer of beeswax, exporting over five million pounds by 1866. In 1964, honey production was around three to four tons, mostly marketed by small-scale independent operators. Honey became a national export product in 1976, and in 1982 the Apiculture Research Center was established to begin professionalizing the activity via studying honey bee management techniques, selecting and rearing queens, and researching nectar-producing plants and hive products. The latter, important to human health, coincide with Cuba’s emphasis on so-called “green” medicine, again the result of economic circumstances that make imported pharmaceuticals too expensive for the population.

In 1990, as a consequence of the Special Period, profound changes in Cuban apiculture occurred according to Lic. Pérez Piñeiro. Beekeeping was basically restructured as a state enterprise, principally due to its economic potential. Cuba needs the cash badly, and organic honey sold on the export market fits the bill. The Guardian newspaper reports “. . . it has become Cuba’s fourth most valuable agricultural export behind fish products, tobacco and drinks, but ahead of the Caribbean island’s more famous sugar and coffee.”

The Havana Times reports: “In 2015, the Cuban beekeeping industry consisted of about 2,000 beekeepers, organized in an industry as efficient in its production as heterogeneous: about 60 Basic Units of Cooperative Production (UBPCs) with more than 400 associates; about 20 Agricultural Production Cooperatives (CPAs), other state-run groups and – the largest group – about 1,100 Credit and Service Cooperatives (CCSs) made up of individual farmers.

“However, the producers do not sell their product in the private market but deliver it all to the Cuban State’s Apicuba Company – except for what they keep for their own individual consumption.

“Apicuba, in turn, distributes the raw product to the only two plants that filter and homogenize the honey. At the end of the long bee-producer-industry-client chain, the exporting company Cubaexport markets the product overseas. Cubaexport monopolizes 98.5 percent of the export sales, a volume that brings into the nation’s economy about 16 million euros, according to Yoandra Valle Vargas, director of Apicuba.”

The article concludes: “Honey is a luxury item for most Cubans with a 340 gram bottle costing 1.60 CUC (1.80 USD), two days’ pay for the average person.”

Again, the Guardian newspaper reports:

“‘All of [Cuba’s] honey can be certified as organic,’ Friedrich told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. ‘Its honey has a very specific, typical taste; in monetary value, it’s a high-ranking product.’

“Now that the United States is easing its embargo following the restoration of diplomatic ties last year, Cuba’s organic honey exporters could see significant growth if the government supports the industry, beekeepers said. Cuba produced more than 7,200 tonnes of organic honey in 2014, worth about $23.3m, according to government statistics cited by the FAO.” Unfortunately, the relationship between the U.S. and Cuba is somewhat in flux with a new presidential administration, and how it will pan out in the future is unclear.

At the moment, therefore, Cuban Apiculture is basically a state-run enterprise, processing the vast majority of the honey crop produced by independent producers associated into cooperatives, via a government-owned enterprise (Apicuba), that sells much of it to the export market for foreign currency income. A good deal of the product is certified organic, bringing a premium price.

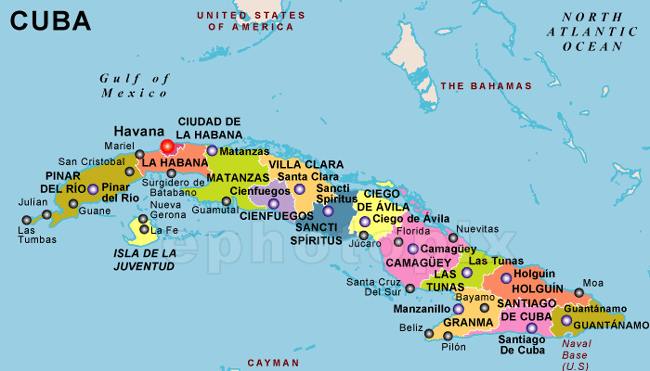

Our beekeeping tour took us to four Cuban provinces: Pinar del Río, Artemisa, Matanzas and Cienfuegos to meet beekeepers in the field. There we learned that the Cuban beekeeping industry is also made up of academics and regulators (trained veterinarians), who often consult with producers in the field. Beekeepers are systematically trained in honey bee management and get their equipment (woodenware and beeswax foundation) from Apicuba. They are visited by veterinarians who regularly inspect apiaries for problems impacting colony health.

Honey is taken off in the beeyard, a process called “castration.” The bees are then removed (brushed), and frames are immediately uncapped and extracted directly into barrels marked with the Apicuba name. One operation featured a trailer rigged with a bicycle frame attached to an extractor that ingeniously delivered the honey directly to the barrel. At the same time, the honey is certified by source (each apiary is marked with GPS coordinates, the producers name and other information) and quickly transported to Apicuba’s bottling plants.

Beekeepers are not allowed to use any chemicals (pesticides or antibiotics) in treating beehives. Varroa mites were introduced into Cuba in 1996. The only treatment permitted is drone-comb trapping to reduce the mite population. All beekeepers are trained and urged to practice this mite-control technique. The incidence of brood diseases is extremely low in the country and not considered a significant issue due to a country-wide genetic selection for hygienic behavior, which is also thought to provide protection for Varroa mites.

Queen-rearing centers have been strategically placed in the country, producing a ready supply of hygienic queen mothers, whose offspring are shipped to producers on request. Cuban bees we were informed, are “creole,” a New World hybridization (mixture) of German, (Apis mellifera mellifera), Italian (A. m. ligustica), and possibly Iberian (A. m. iberica) with some Caucasian (A. m. caucasica) thrown in.

Annual re-queening is mandated for each colony due to the fact that some 12 honey plants in the country produce an almost continuous nectar flow. Queens in essence are “worn out” due to extended egg laying for twelve-month periods. Combs are renovated after fifteen brood cycles, sent to Apicuba for wax rendering, and returned along with replacement foundation to the beekeeper.

Special circumstances in Cuban beekeeping exist in two arenas. One is the apparent absence of Africanized honey bees. This is surprising considering that bee’s presence in most of the Caribbean region. The gentleness of the honey bees in apiaries our group visited appeared to be a testament to this. We often arrived at apiaries, however, after the “castration,” opening and examining colonies that were not in peak condition. The Havana Times piece contains one bit of evidence suggesting something different: “Reinaldo Santana, a beekeeper who has lived for decades on the slopes of the Escambray mountain range…uses country expressions to describe the bees’ anger: ‘Sometimes they mob you and set you a blaze. This is a job for brave roosters.’ ”

Varroa is another intriguing topic. The role of viruses vectored by these mites is different everywhere; it is these organisms, not Varroa’s parasitic behavior, that are potentially most damaging to honey bee colonies. Islands are notable in this regard. Researchers on Fernando de Noronha off the coast of Brazil known for European honey bees surviving Varroa without treatment have concluded: “We predict that this honey bee population is a ticking time-bomb, protected by its isolated position and small population size. This unique association between mite and bee persists due to the evolution of low Varroa reproduction rates. So the population is not adapted to tolerate Varroa and Deformed Wing Virus, rather the viral quasispecies has simply not yet evolved the necessary mutations to produce a virulent variant.”

Is it possible that both the Africanized honey bee absence in Cuba, as well as successful limited Varroa treatment using drone trapping along with hygienic behavior, are the results of an extremely tightly controlled honey bee population with minimal influence from imported genes and viruses? Prohibited honey bee imports into the country, combined with continuous selection for hygienic behavior, and coupled with rigorous inspection at ports intercepting any possible feral swarms from other parts of the region, would certainly contribute to both situations.

Finally, as noted above, Cuba’s precarious economic situation, precipitated by the Special Period, and still being exacerbated by much of U.S. policy, has resulted in emphasis on natural and organic (less expensive) beekeeping techniques, rather than more costly, often fossil-fuel-based industrialized beekeeping strategies, found in many developed countries.

According to a post from Pest Control Technology, Robert Owen in a research essay argues that human activity is a key driver in the spread of pathogens affecting the European honey bee (Apis mellifera). These include:

Regular, large-scale and loosely-regulated movement of bee colonies for commercial pollination. (For instance, in February 2016 alone, of the 2.66 million managed bee colonies in the United States, 1.8 million were transported to California for almond crop pollination.)

Carelessness in the application of Integrated Pest Management principles leading to overuse of pesticides and antibiotics, resulting in increased resistance to them among honey bee parasites and pathogens such as the Varroa destructor mite and the American Foul Brood bacterium (Paenibacillus larvae).

The international trade in honey bees and honey bee products that has enabled the global spread of pathogens such as Varroa destructor, tracheal mite (Acarapis woodi), Nosema ceranae, small hive beetle (Aethina tumida), and the fungal disease chalkbrood (Ascosphaera apis).Lack of skill and dedication among hobbyist beekeepers to adequately inspect and manage colonies for disease.

Owen offers several suggestions for changes in human behavior to improve honey bee health, including:

Stronger regulations both of global transport of honey bees and bee products and of migratory beekeeping practices within countries for commercial pollination.

Greater adherence to Integrated Pest Management practices among both commercial and hobbyist beekeepers.

Increased education of beekeepers on pathogen management (perhaps requiring such education for registration as a beekeeper). Deeper support networks for hobby beekeepers, aided by scientists, beekeeping associations and government.

He concludes: “The problems facing honey bees today are complex and will not be easy to mitigate. The role of inappropriate human action in the spread of pathogens and the resulting high numbers of colony losses needs to be brought into the fore of management and policy decisions if we are to reduce colony losses to acceptable levels.”

The recipe above for healthier honey bees sounds a whole lot like the current Cuban beekeeping scene our group saw on display. It would be beneficial for beekeepers everywhere to explore more deeply Cuban beekeeping practice. The more “apicentric” focus on the island is a “kinder and gentler” approach to managing Apis mellifera. Perhaps this associates the insect in a similar caring way to how Cubans feel about their enigmatic peasant girl from the province of Guantánamo (Guantanamera).